0 comments | 3 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

0 comments | 3 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been described as a watershed moment for the EU. But has the conflict changed the views of ordinary citizens about European integration and immigration? Using new data from the Netherlands, Sander Kunst and Sander Steijn assess how attitudes have changed among Dutch citizens following the invasion.

On 24 February 2022, the Russian army invaded Ukraine, marking the beginning of the most significant military conflict in Europe since World War II. Although the European Union (EU) is not directly involved in the war, it has played a key role in it by supplying weapons and financial aid to Ukraine, receiving refugees and imposing sanctions on Russia. It is within this context that the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, declared the war a ‘watershed moment’ for the EU and attitudes towards its future significance and operation.

While European leaders may indeed perceive the war in Ukraine as a watershed moment for European cooperation, the question is whether it has also affected public opinion about the EU and globalisation in a broader sense. Has there been any significant change since the Russian invasion? Are there any differences in this respect between different groups in society? Using high-quality data about Dutch public opinion, we are able to shed more light on whether the war in Ukraine does indeed represent a watershed moment in citizens’ attitudes towards the EU and immigration.

Earlier studies conducted by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) into Dutch public opinion about the EU have shown that most people in the Netherlands support the country’s EU membership, although they are not universally positive. But has this attitude shifted since the beginning of the war in Ukraine?

One potential reason why this might have occurred is that there may have been a short-term ‘rally ‘round the flag’ effect. Outside threats, like a pandemic, may cause a temporary rise in trust in the national government. In times of crisis, decisive action by those in authority may give them a boost in terms of support. The EU’s actions, such as supplying weapons to Ukraine and imposing sanctions on Russia, may have produced a rally ‘round the European flag’ and hence increased appreciation of the EU.

A second reason why this might have occurred is that the war may have had the long-term effect of making citizens more aware of the Netherlands’ many international connections. This may have lent additional credence to the ‘together we’re stronger’ argument that Dutch citizens often use to explain their support for EU membership.

Furthermore, the invasion of Ukraine may have affected attitudes towards migration. The arrival of Ukrainian refugees has brought the consequences of migration closer to home for the Dutch. This may have led to perceptions of a material and cultural threat among the population and hence stronger anti-immigration sentiment. Nevertheless, Ukrainian refugees generally received a warmer welcome than refugees from countries like Syria who arrived during the ‘refugee crisis’. It is therefore not unthinkable that the later refugee influx had less of an effect on attitudes towards migration.

To confirm whether public opinion has indeed changed, we examined data from the Nederland in Beeld (Overview of the Netherlands) population survey, or NiB for short. Launched in July 2021, the NiB is the SCP’s ongoing research tool. Each month, the SCP picks a random sample of Dutch residents (aged 18+) from the Key Register of Persons to approach for the survey. After weighting has been applied as a correction for non-response, the pool of respondents accurately reflects the Dutch adult population.

Because the survey is being administered continuously and involves a large sample (~400 respondents per month), the SCP is able to report on Dutch political and social attitudes on a monthly basis. To test the assumption that the war in Ukraine has caused a shift in attitudes towards globalisation, we asked respondents to react to four statements.

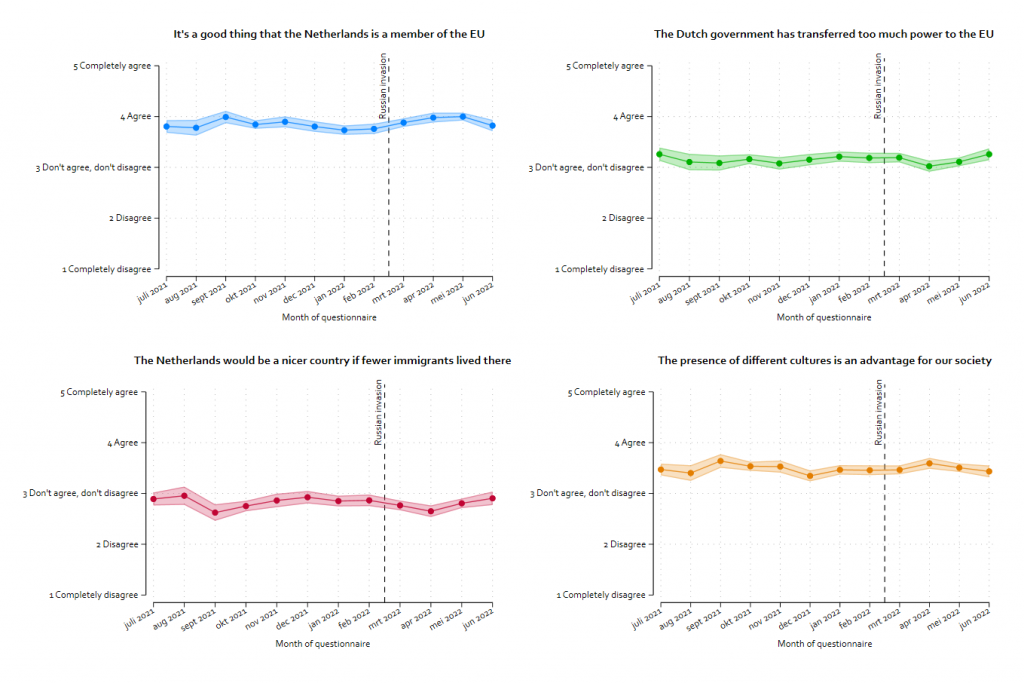

Two of these were about the EU specifically: (1) It’s a good thing that the Netherlands is a member of the EU; and (2) The Dutch government has transferred too much power to the EU. The other two statements, which related to immigration and cultural diversity, were: (3) The Netherlands would be a nicer country if fewer immigrants lived there; and (4) The presence of different cultures is an advantage for our society.

How has Dutch public opinion evolved with regard to these four issues? Figure 1 shows the evolution between July 2021 and June 2022. Although the Dutch are largely supportive of EU membership (top left), they are fairly critical when it comes to handing over power to the EU (top right). Generally speaking, we have seen no significant shift in attitudes towards the EU, far less a watershed.

As regards support for EU membership, there has been a slight increase after February 2022, but no more than 1/8 of a standard deviation. To conclude, our data suggest that there has been no significant shift in these attitudes. At the same time, attitudes towards migration (bottom left) and cultural diversity (bottom right) have not changed fundamentally either.

Figure 1: Attitudes have remained largely stable

Note: The confidence level shown is 95%. Source: NiB (SCP 2022)

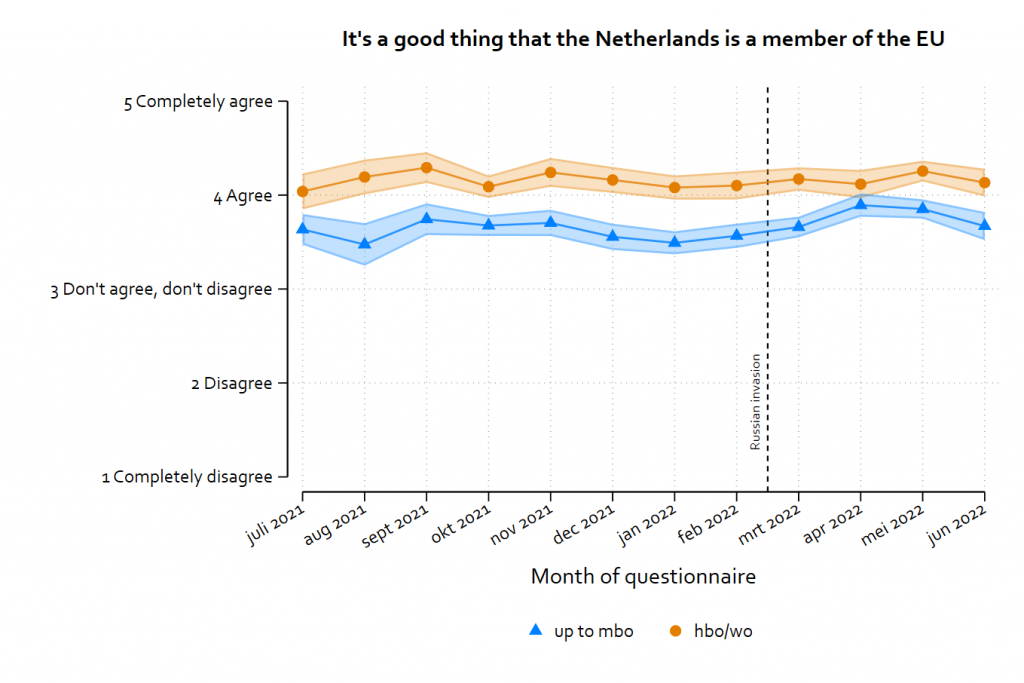

However, is there any evidence of differences in underlying public opinion dynamics between certain groups? We have found time and time again that education level is a key dividing line with regard to attitudes toward globalisation: people with a senior secondary vocational education (MBO) diploma as their highest level of qualification tend to be warier of these issues than those educated to higher professional education (HBO) or university (WO) level.

For most outcomes, the underlying group dynamics have remained stable. Once again, support for EU membership is the exception. Although those educated to HBO and WO level are still more positive on average than those educated up to MBO level, the gap has narrowed somewhat since the Russian invasion. That said, the outcomes are subject to substantial margins of uncertainty and monthly fluctuations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Support for EU membership by education level

Note: The confidence level shown is 95%. Source: NiB (SCP 2022)

Previously, the SCP found the Dutch generally have nuanced attitudes not only towards the EU specifically, but also towards globalisation in a broader sense. Judging by our results, the war in Ukraine does not appear to have been a watershed moment for how Dutch citizens view the EU or issues like immigration and cultural diversity. Consequently, we see no reason to update our previous findings.

However, it is important to note that our study examined relatively broad perceptions of the EU. It is entirely possible there have been attitude shifts with regard to more specific policy areas, like defence or energy policy. A comparison with developments in other countries would be an interesting line of inquiry. It is conceivable that attitudes have shifted in a different direction in other countries, for example those located geographically closer to Ukraine, or those who received many more or fewer Ukrainian refugees.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union

Sander Kunst obtained a PhD in Sociology from the University of Amsterdam, and currently works as a Researcher for The Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) where he studies public opinion towards the European Union and globalisation.

Sander Steijn works as a Programme Leader at the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP). He leads the ‘Netherlands in a globalising world’ programme, which studies how international connectedness shapes the lives of inhabitants of the Netherlands, and contrasts people’s conceptions of local, national, and transnational forms of solidarity with the forms of solidarity that are currently present (or developed) in policy.

© LSE 2023