Is there such a thing as a Jewish accent? According to the following definition from The Pimsleur Language Blog, there surely is such a phenomenon:

Accents are born when speakers of the same language become isolated and, through evolution, unwittingly agree on new names or pronunciations for words. Dozens of these small changes result in a local “code” that’s not easily understood by outsiders.

“Accents are born when speakers of the same language become isolated and, through evolution, unwittingly agree on new names or pronunciations for words. Dozens of these small changes result in a local “code” that’s not easily understood by outsiders.”

The Pimsleur Language Blog

“Accents are born when speakers of the same language become isolated and, through evolution, unwittingly agree on new names or pronunciations for words. Dozens of these small changes result in a local “code” that’s not easily understood by outsiders.”

Ever since the first exile from the Land of Israel and the dispersion across the globe, Jews have been subjected to this kind of isolation. By the time of the emancipation, Jews had formed themselves into separate cultural entities. We were forced to live in ghettos and eventually got used to the idea of living among our own. Even after the emancipation in the 19th century, most Jews decided to remain within their own communities whether in Europe or elsewhere. Thus in many countries where Jews settled, they initiated their own “lingo,” often suffused with Yiddish, Ladino or Arabic (depending on where they were from), and with it the Jewish accent evolved.

The phenomenon of accents is, of course, not unique to Jews.

Growing up in South Africa, I was acutely aware of the ethnic diversity of the country and, with it, the sound of many different languages. By the time I was 11 years old, I was already able to distinguish the difference between a Zulu accent and a Sotho accent. From a very young age, I was taken care of by a nanny. Although I didn’t speak Southern Sotho (her language), I got to understand a few words and the nuances and cadences of the way she spoke.

We were taught English and Afrikaans (Dutch dialect) throughout our schooling. I had grandparents who came from Lithuania and spoke English with strong Yiddish accents.

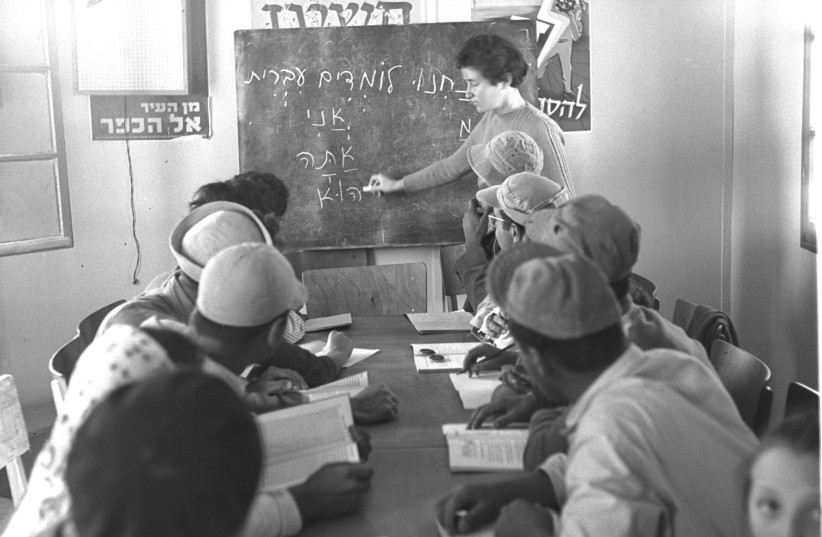

An Ulpan in Dimona, 1955. (credit: MOSHE PRIDAN/GPO)

An Ulpan in Dimona, 1955. (credit: MOSHE PRIDAN/GPO)As I grew older and after I left South Africa for the UK and Europe, I was exposed to the incredible richness of languages, dialects, and accents. I learned to speak six of these and became fascinated by the similarities and differences of European language groups. I started working with international clients and soon began to recognize the difference between a Dutch accent and a Flemish accent. For a while I lived in Holland and worked in Belgium. At one point, I had an interview for a sales job in Amsterdam. I was called back by the company for a second interview. They conducted the interview in Dutch, and afterwards I was offered the job. I was curious to know why they wanted to interview me in Dutch.

“We wanted to make sure that you did not have a Belgian accent,” the fellow explained. “Dutch customers are often turned off by the Flemish accent.”

I was a little shocked. I had expected him to say something disparaging about my South African Dutch accent.

I also lived in Switzerland and picked up Swiss German. In the German-speaking part of Switzerland, the Cantonal dialects are so different that they sound like different languages.

Becoming an immigrant taught me that accents define us. In London, where I lived for most of my life, accents are deeply ingrained in the social fabric of society. In London in the 1970s, I remember how people could sometimes not understand me. This was especially problematic when I was leading seminars or workshops or speaking at conferences. I had to work on my vowel sounds which had been squashed by my Johannesburg accent. The Brits referred to it as “your South Efrican twang.”

Accents do define us.

They project our cultural identity to the listener and play into the positive or negative prejudices of that person. This has always been exceptionally true in the UK.

George Bernard Shaw was intensely aware of these facts when he wrote the play Pygmalion, which later became immortalized in Lerner and Loewe’s musical My Fair Lady. It was the story of Eliza Doolittle, the Cockney flower seller whom Professor Higgins transformed into an “aristocrat” by coaching and bullying her into changing her accent, body language and behavior.

In this respect, the UK is a fascinating place. The British class system is heavily reflected in the way people speak. Sometimes jobs are won or lost on the strengths of how well you enunciate words and express yourself verbally. One is perceived as either working class, middle class or upper class.

The United States has its fair share of different accents and ways of speaking. These include Maine, New England English, Pacific Northwest, California, Midwestern American English, Southern American English, Hawaii English and Pidgin, New Orleans and Cajun English, East Coast City dialects (Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and New York City), High Tider (North Carolina Coast) and the range of Canadian accents. There are also ethnic accents that are identifiable among the Afro-Caribbean and Hispanic communities.

Because the United States has become a melting pot of cultures over the centuries, Americans are a little less judgmental about what people sound like. The southern drawl or New York accent have become hallmarks of American identity which have found their way into literature, songwriting, and the movies.

During my 40-year career of training leaders and managers across the globe, I have learned that accents can be a help, not a hindrance. An accent makes one stand out in a crowd and allows you to make an impact as long as you enunciate your words, speak clearly and at the right pace. This also applies to non-native English speakers.

Accents in Israel

In Israel, where Jews have now lived as an independent nation for 74 years, accents have played a significant role in shaping society. Since the establishment of the state in 1948, immigrants have flooded into the country from almost everywhere. At first, Middle Eastern and East European accents predominated. As the decades passed, immigration from other parts of the globe increased, especially from Russia, the US, France, the UK, South Africa and Australia and latterly Ethiopia. The Israeli government from its very inception has recognized the importance of absorbing immigrants by introducing the ulpan system, where immigrants are sent for a period of six months to learn how to speak modern Hebrew. Younger olim (immigrants) are usually more successful in acquiring the language. It takes a good few years before the next generation begins to speak Hebrew without a marked Diaspora accent.

Israelis have a very distinct Hebrew accent. They roll their “r’s” and pronounce words with the correct syllables emphasized in the right places. Years ago, it was easy to recognize the difference between Ashkenazi Jews and Sephardi Jews by virtue of how they pronounced certain consonants and vowel sounds. This is less distinguishable today, as the younger generation have blended into a more homogeneous society. However, it is still possible to pick up “origin” nuances from the accents of older people. Native English speakers do stand out quite conspicuously when they speak Hebrew. Israelis can tell immediately whether the person they are speaking to is an immigrant from the US, Canada or other English-speaking countries.

For the past seven years I have volunteered to coach young people at a number of Jerusalem academic institutions. I have found the experience both rewarding and instructive. It has helped me to understand the mindsets of the modern Israeli generation. Most of my students are at least 40 years younger than I am. They are all incredibly keen to learn English.

Many have learned English at school, but many more have picked it up by watching hours and hours of American television. Young Israelis aspire to acquire English in order to further their careers in industries such as hi-tech. Many struggle with English pronunciation and the “insane” rules of English grammar, which are as confusing to them as some aspects of Hebrew grammar are perplexing to me. Many are embarrassed by their accents and their struggle to be heard and understood. I always empathize with them and explain what I was taught years ago: Acquiring fluency in a language means taking risks, moving out of your comfort zone, and spending time talking with native speakers. The method is known as “total immersion,” learning to speak the language in the same way as we acquire our first language. The more we hear the sounds of words, the more we unconsciously imitate them (even with an accent) and thus become more comfortable in expressing ourselves.

After living in Israel for the last nine years and learning cheder Hebrew since I was four years old, I still force myself to persevere, encouraged by my American wife whose Hebrew is far more fluent than mine is. I do make mistakes; nevertheless, I soldier on and go out of my way to initiate conversations with Israelis who appreciate my efforts. Every now and then I experience setbacks, like one recent morning when I called a medical facility to make an appointment. After I had painstakingly articulated my request in well-rehearsed Hebrew, the Israeli receptionist replied in English with her delightful Sabra accent:

“So which department do you want me to connect you to, sir?”

On that occasion, I let her win and carried on the conversation in my native modified South African, British mélange of an accent. ■