Top Stories

Most read stories of the month

Week

Latest articles of the week

BELMONT, Mass. — The National Association for Armenian Research and Studies (NAASR) hosted an online webinar lecture on the history of the Armenian connection with Jerusalem on January 13 with Prof. Claude Mutafian of Paris, the noted French mathematician turned history scholar.

Mutafian taught mathematics in French universities as well as around the world for more than 40 years; but always with a passion for history, he has conducted a significant amount of research and writing in this field as well, obtaining a PhD from the Sorbonne in 2002 with a thesis on the “Armenian Diplomacy in the Levant During the Crusades.” The period of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and its relation with the Crusaders is his area of specialty, and the role of Armenians in Jerusalem forms a major part of the history of that era.

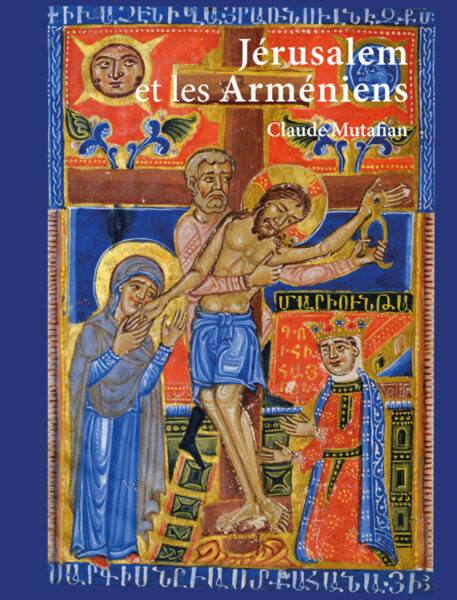

The lecture, titled “Jerusalem and the Armenians: Until the Ottoman Conquest (1516),” was co-sponsored by NAASR (Belmont, MA), the Ararat-Eskijian Museum (Los Angeles) and the UCLA Promise Armenian Institute. Marc Mamigonian of NAASR and Maggie Goschin of the Ararat-Eskijian Museum introduced Mutafian, who spoke via Zoom from France.

Early Armenian Connections to Jerusalem

Mutafian stated that the Armenian people seem to have been “obsessed” with the holy city of Jerusalem since the nation’s conversion to Christianity in the 4th century. As an example of this, he explained that almost every important figure in the history of Armenia, until the late Middle Ages, seems to have had a desire to make the trip to Jerusalem. St. Gregory the Illuminator, after converting Armenia to Christianity; Mesrob Mashtots, after inventing the Armenian alphabet; and Movses Khorenatsi, after writing one the first complete histories of Armenia all travelled to Jerusalem, Mutafian stated.

He also pointed out that the Old City of Jerusalem is divided into four quarters: Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Armenian; the fact that Armenians have their own quarter rather than being a part of the Christian Quarter is more proof of the importance of Armenians in the history of that city. He also discussed the opening of the new Mardigian Armenian Museum near the Zion Gate. He was a consultant on this project, and it gave him the occasion for the publication of his new book, Jerusalem et Les Armeniens: Jusqu’a La Conquette Ottomane, 1516 (Jerusalem and the Armenians: Until the Ottoman Conquest, 1516), which was the basis for the lecture.

Jerusalem’s Armenian quarter is dominated by the Monastery of Sts. James (James the Great and James the Lesser, two of the 12 disciples of Christ). The monastery has the largest and most important collection of Armenian treasures (art, books, etc.) outside of Armenia. For example, only seven manuscripts illuminated by Toros Roslin, considered the greatest illuminated manuscript artist in Armenian history, remain; four are in Jerusalem.

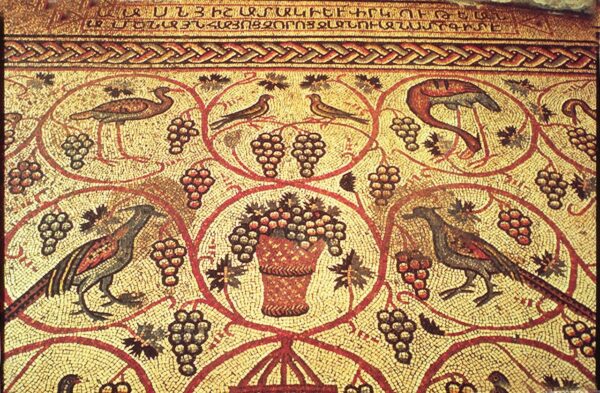

The oldest examples of the Armenian alphabet are also located in the Holy Land; a large, intricate floor mosaic with a text dedicating the artwork in the memory of all Armenians, dates to the 6th century. An even older inscription with Armenian lettering dating to the 5th century was recently found in Nazareth. The first printed Armenian alphabet, made in 1486, is even connected to Jerusalem. It was made by a German traveler interested in languages who visited Jerusalem and learned the Armenian alphabet while he was there.

The 6th-century mosaic, with its images of birds, was originally discovered in a chapel near the Damascus Gate, on the north side of the Old City, at the margin of the Christian and Muslim Quarters. However, the atmosphere where the mosaic was located was extremely humid and damp; as a result, the mosaic was deteriorating, as Mutafian noticed on successive visits to Jerusalem. He stated that there was some controversy around the suggestion that the mosaic should be moved to a safer location; if this was done, there would be no proof of the Armenian presence in that chapel, which was shown to be the Armenian Chapel of St. Polyeuctos (a 3rd-century Roman martyr in the city of Malatia, historic Armenia). Ultimately, the mosaic was moved to the the central courtyard of the new Mardigian Museum. Mutafian’s opinion is that it is better this way, because the mosaic will be preserved, and more people will see it. However, he hopes that a replica can be installed in the Chapel of St. Polyeuctos.

Dawn of the Cilician Period

Mutafian then turned to his area of expertise, Cilicia. During the 11th century, when the Turks were invading Asia Minor, Armenians moved west into the Byzantine Empire settling in different regions including Cilicia and Cappadocia. According to Mutafian, the reason Armenians went to Cilicia was that there were already Armenian settlers there.

Two noble families, the Roupenians and the Hetoumians, settled in Cilicia and attempted to recreate a new “Kingdom of Armenia.” The Roupenians ended up winning the power struggle just in time for the Crusaders to show up in the region looking to “liberate” Jerusalem from the Turks. It just so happens that the region of Cilicia is directly on the land route from Europe via Constantinople to Jerusalem. The Crusaders, known in the East generically as “Franks,” naturally passed through the region, and formed close alliances with the Armenian aristocracy.

Not only in Cilicia itself but also in other regions of Asia Minor, the Armenians had become so prevalent after the 11th century that the Crusaders thought of it as their original homeland. According to Mutafian, when one of the leaders of the First Crusade entered Caesarea (i.e. Gesaria, modern Kayseri, Turkey), a city that was the traditional capital of the Greek-speaking region of Cappadocia, it was so full of Armenians that in his memoirs he wrote “now we entered Armenia.”

The Crusaders fought the forces of the Seljuk Turks, conquering the city of Jerusalem and other regions of the Levant. They set up four states, namely the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Both the County of Edessa and the Principality of Antioch border on the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, so the Franks had a lot of contact with the Armenians. In fact, the majority population in the County of Edessa was Armenian. (The County of Edessa was centered around the city of Edessa, today’s Urfa, Turkey.)

Due to this extensive contact, Crusader nobility often married Armenian princesses. Because Armenians were Christians local to the region, yet not affiliated with the Byzantine Empire and its Greek Orthodox Church which was a major rival to the Roman Catholic Crusaders, Armenian women made ideal queens for the Crusader states. In fact, the first two Latin Kings of Jerusalem married daughters of Armenian lords; thus the first two Queens of Jerusalem in the Crusader period were Armenian: the wife of King Baldwin I was Arda, daughter of Toros, Lord of Marash; and the wife of King Baldwin II was Morphia, daughter of Gabriel, Lord of Malatia.

On the death of King Baldwin II, his widow Morphia was left with four daughters and no sons. The eldest daughter, Melisende, inherited the throne as Queen of Jerusalem. According to Mutafian, Melisende impressed the Crusaders as a capable female ruler, stating that “all the Frankish writers of that time are fascinated by her.” Mutafian also mentioned that when Toros II, lord of Cilician Armenia, visited the city, the King of Jerusalem went out to meet him with great honor, showing the importance of the Armenians as a regional power at the time.

Mutafian underscored the importance of the Armenians in that time period by mentioning the visit of Toros II, lord of Cilician Armenia to Jerusalem. The King of Jerusalem, Amalric I (son of Queen Melisende) went out to meet him with great honor, showing the importance of the Armenians as a major regional power.

The Armenians Official Recreate their Kingdom

Mutafian continued with his discussion by mentioning that in 1187, the Kurdish warrior Saladin, leader of the Muslim forces, retook Jerusalem from the Crusaders. He also captured the last King of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan, in the Battle of Hattin. This provoked the Third Crusade, led by King Richard the Lionheart of England and Frederick Barbarossa, the German ruler of what was known as the Holy Roman Empire, based in Central Europe.

Richard the Lionheart went to the Holy Land by sea, and on his way conquered the island of Cyprus, giving it to the former King of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan. Lusignan kept his title “King of Jerusalem,” and ruled as “King of Cyprus and Jerusalem,” though the latter was in name only. Richard then landed in the Levant where he fought Saladin and reconquered some territory, though not Jerusalem itself. Nevertheless, the coastal territory thus reconquered (including most of the coastline of present-day Lebanon and Israel) was titled “Kingdom of Jerusalem” and the Lusignan family became its rulers while still holding sway over Cyprus. Later, the same family would be connected with the Kingdom of Armenia.

Frederick Barbarossa, in the same Crusade, went by land, travelling through Cilicia. The Lord of Armenian Cilicia, Prince Levon II, sent an embassy to Frederick offering help in crossing the difficult Taurus Mountains (which separate Asia Minor from Syria). In exchange, Levon asked for the coronation of himself as King, which would be Frederick’s right as an Emperor. Frederick complied with this request.

In this way, in 1198, Prince Levon II was crowned King Levon I, recreating the Kingdom of Armenia — outside of Armenia — as Mutafian pointed out. At his coronation Levon received crowns from the German (“Holy Roman”) Emperor, the Byzantine (“Roman”) Emperor, and the Pope of Rome. Levon was not titled “Armenian King of Cilicia” or “King of Cilician Armenia,” nomenclature used by later historians. Rather, the coins which he minted, as Mutafian stressed, are inscribed in Armenian script with the words “Levon Takavor Amenayn Hayots” (Levon, King of All Armenians). Mutafian then showed an image of the coin minted by Levon’s contemporary, Amalric of Cyprus, with the inscription “Amalric, by the grace of God, King of Jerusalem and Cyprus.” According to Mutafian, these became the two main Christian powers in the region for the next hundred years, until the end of the Crusader period. As for the struggle over control of Cilicia between Levon’s family, the Roupenians, and their rivals the Hetoumians, the feud finally ended with the marriage of Levon’s daughter and heir Queen Zabel to Prince Hetoum, who then became King Hetoum. “After that, there were no more problems,” stated Mutafian, who referred to this as “the matrimonial policy.”

King Hetoum Travels to Mongolia on Foot

By the middle of the 13th century, “everything changes,” Mutafian stated. In Cairo, a group of Turkish slaves had taken power and imposed themselves as Sultans of Egypt. They were known as Mamluks, and their empire soon conquered all of Syria. During the same time period, the Mongols, who had originated from Central Asia, and had conquered a vast Empire under Genghis Khan, began to conquer the areas of the Middle East under the successors of Genghis. They conquered most of the territories of the region, up to Asia Minor. At first the Mongols were strongly anti-Muslim. Therefore, in the regional power struggle between the Mongols and the Mamluks, King Hetoum decided to ally himself with the Mongols. Mutafian showed the audience an image from an historic illuminated manuscript of the Nativity of Christ including the visit of the Three Kings. A note written beside the image states that “the Tatars just arrived,” referring to the Mongols, and depicting them as protectors of the Armenians.

Hetoum made the remarkable journey all the way to the Mongol capital, Karakorum, in present-day Mongolia, in order to seal the alliance. This political move allowed the Kingdom of Armenia to survive in Cilicia for another century. Mutafian commented that Cilician Armenia had a few political geniuses, such as Hetoum I and his father-in-law Levon I, and unfortunately Armenia cannot say the same today. Hetoum also patronized the Christian sites in the Holy Land; the wooden doors to the Basilica of Bethlehem were gifted by him, which had inscriptions in Armenian and Arabic stating them to be the gift of King Hetoum.

Unfortunately, the alliance with the Mongols was not too stable because Armenia was far from the Mongol homeland. In the end, the Mamluks won out and in 1375 put an end to the Kingdom of Armenia, incorporating Cilicia into the lands of the Mamluk Sultanate. Despite that, Armenians continued to be important players in the region. With Armenians neutralized as a political force, they were no longer dangerous to the Mamluk Empire as were the Latin (Western European) and Greek powers; therefore the Mamluks decided to protect the Armenians as a Christian minority. There is an inscription left by the Mamluks at the door to the St. James Armenian Monastery compound in Jerusalem, stating “Everyone who would do harm to the Armenians will be punished.”

Under the rule of the Mamluks, the region became stabilized and was again safe for pilgrims. The number of Western travelers making the pilgrimage to Jerusalem grew, and many pilgrims wrote memoirs of their journey. According to Mutafian “everyone had a chapter in their manuscript dedicated to the Armenians,” showing that they continued to have a noticeable presence in the area. One European called the Armenians “our principal allies,” as well as noting that the Armenian community included the most beautiful women in Jerusalem! But Mutafian showed that there was also animosity towards Armenians by other Christian nations, displaying a chapter from a book entitled “About the Armenians and Their Errors.” Since the 5th century, when the Armenians refused to recognize the Council of Chalcedon, they have been considered heretics by the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches. Especially between Armenians and Greeks in that era, said Mutafian, there was a terrible hatred.

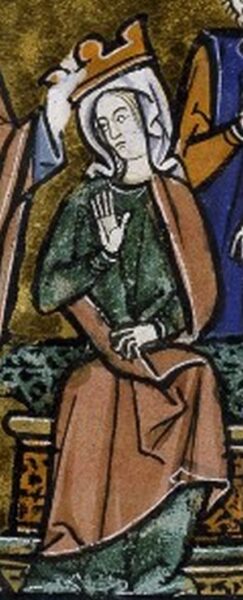

As for the royal dynasty of Armenia, by the time of the fall of Cilicia, it had been inherited by a branch of the Lusignan family (of French Crusader origin), who also reigned as Kings of Cyprus. The last king of Armenia, Levon V, was a Lusignan; he was crowned in 1374 and the Mamluks destroyed his kingdom the following year. Levon V was imprisoned in Cairo, along with Queen Marioun, the wife of the last king that had ruled before Levon V. Mutafian showed his audience an image of an illuminated Gospel miniature by renowned artist of the time Sarkis Bidzag, which depicted the queen, and has a text which reads “This is Marioun, Queen of the Armenians.”

Queen Marioun, when taken prisoner, was treated kindly by the Mamluk Sultan. He asked her if she desired anything, and she responded “I wish to end my life in Jerusalem.” Mutafian noted the symbolism of the close connection between Jerusalem and the Armenian people by pointing out that the last Queen of Armenia decided to finish her life in Jerusalem. For this reason, Mutafian chose her image for the cover of his new book.

As for Levon V, he was freed by the Sultan and came to Paris, where he died without an heir. He is buried in the same chapel that contains the cenotaphs of all the Kings of France. The title “King of Armenia” was then inherited by his closest relative, James I, King of Cyprus. James was also “King of Jerusalem,” in name only of course. As the Kingdom of Cyprus fell, the great-grandson of James was married to a Venetian noblewoman who tried to hand the crown of “Jerusalem, Cyprus, and Armenia” to the Doge of Venice. But instead, her husband’s sister took the title and married a prince from the House of Savoy, which later came to rule Italy after its unification in 1861. Apparently, the title was still used by the Kings of Italy until all extraneous titled were abandoned by King Victor Emmanuel III at the beginning of the 20th century.

A Labor of Love

Mutafian noted that Jerusalem has been a center of Armenian culture and especially manuscript production. The oldest Armenian manuscript copied in Jerusalem was from 1215 and is kept by the Armenian Catholic Mekhitarist Brotherhood in Venice. There are also many manuscript treasures which did not originate in Jerusalem but are kept there; one of the outstanding examples is the Gospel of Queen Keran, created in 1272 at the order of the Queen. The manuscript includes one of the most famous images created by artist Toros Roslin, a depiction of King Levon II and Queen Keran (Guerane) with their five oldest children. Mutafian pointed out to the audience that the royal couple had 16 children in all.

Mutafian noted that although the book is not yet available in English, is a 500 page book which includes 1000 pictures. He suggested that those who don’t read French would be able to greatly appreciate the images contained in the book, which is available for delivery in the US via Amazon and other online sources. Mutafian suggested that those who are interested purchase the book direct from the publisher, Les Belles Lettres, here: https://www.lesbelleslettres.com/livre/9782251452968/jerusalem-et-les-armeniens

Mutafian is also planning to come to the US to speak in more detail about his book in person later this year.