The atmosphere cleans itself by creating a molecule called hydroxide (OH) through a previously unknown mechanism, according to a new, peer-reviewed study.

Hydroxide oxidises many gases released by natural processes and human activity, decomposing them into water-soluble products that can be washed away and removed from the atmosphere. Nobel Prize Laureate Paul Crutzen referred to hydroxide as the “detergent of the atmosphere.”

Up until now, scientists thought that hydroxide was mainly formed by sunlight, but the new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last week found that a strong electric field that exists at the surface between airborne water droplets and the surrounding air can create OH as well.

“The conventional wisdom is that you have to make OH by photochemistry or redox chemistry. You have to have sunlight or metals acting as catalysts,” said Sergey Nizkorodov, a University of California, Irvine professor of chemistry and a member of the research team, in a press release. “What this paper says in essence is you don’t need any of this. In the pure water itself, OH can be created spontaneously by the special conditions on the surface of the droplets.”

The research team built on prior research by Stanford University scientists led by Richard Zare, who found that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was spontaneously formed on the surfaces of water droplets.

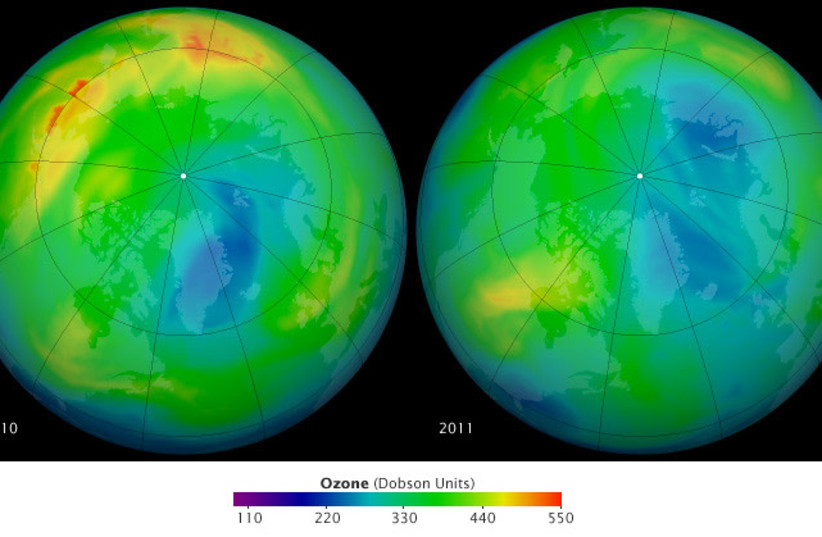

Arctic Ozone Loss | NASA image acquired March 19, 2011 (credit: FLICKR)

Arctic Ozone Loss | NASA image acquired March 19, 2011 (credit: FLICKR)The team conducted the study by measuring OH concentrations in various vials, some containing an air-water surface and others containing only water without air. They then tracked OH production in darkness by including a “probe” molecule that lights up when it reacts with OH.

The scientists found that OH production rates in darkness were the same or even higher than other drivers like sunlight exposure.

“Enough of OH will be created to compete with other known OH sources,” said Nizkorodov. “At night, when there is no photochemistry, OH is still produced and it is produced at a higher rate than would otherwise happen.”

Christian George, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Lyon in France and lead author of the new study, explained that “OH is a key player in the story of atmospheric chemistry. It initiates the reactions that break down airborne pollutants and helps to remove noxious chemicals such as sulfur dioxide and nitric oxide, which are poisonous gases, from the atmosphere. Thus, having a full understanding of its sources and sinks is key to understanding and mitigating air pollution.”

Study’s findings to alter how air pollution models are formed

The team noted that the new findings alter understanding of the sources of OH and will affect how researchers build computer models forecasting air pollution.

“It could change air pollution models quite significantly,” Nizkorodov said. “OH is an important oxidant inside water droplets and the main assumption in the models is that OH comes from the air, it’s not produced in the droplet directly.”

Nizkorodov added that the next step should be to perform carefully designed experiments in the real atmosphere in different parts of the world.

“A lot of people will read this but will not initially believe it and will either try to reproduce it or try to do experiments to prove it wrong,” said Nizkorodov. “There will be many lab experiments following up on this for sure.”

Researchers from the Weizmann Institute, France’s University Claude Bernard and China’s Guangdong University of Technology also took part in the study, which was funded by the European Research Council.