On 15 April 2020, the inhabitants of Khartoum, Sudan’s capital city, braved a newly imposed covid-19 lockdown to wait in line under the sun, hoping to buy bread, cooking gas, and fuel. The hot season was coming and, with temperatures steadily approaching 40°C, the daily grind of queuing was becoming unbearable. Family members took turns. Overnight, people left cars and cooking bottles to mark their positions in the queue.

Chronic shortages of basic goods and soaring inflation have come to define the life of ordinary Sudanese. In villages and towns that rely on gasoline pumps – such as Port Sudan – the taps have often run dry, forcing people to queue to buy barrels of water. When the government scrapes together enough foreign currency to import basic goods such as fuel and wheat, this relieves some of the pressure.

The April 2019 revolution, which ended Omar al-Bashir’s 30-year military rule, brought hope that a civilian regime would emerge to govern Sudan. But – less than a year since the appointment of the transitional prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok – this hope is fading fast.

In February 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) described Sudan’s economic prospects as “alarming” – unusually blunt language by its standards. Then came covid-19 and the associated global economic downturn. The IMF revised its assessment: Sudan’s GDP would shrink by 7.2 percent in 2020. By April, inflation had risen to almost 100 percent (one independent estimate finds that inflation may have hit around 116 percent). Adding to this grim catalogue of calamities, the swarms of locusts that have ravaged the Horn of Africa in the worst outbreak in 70 years are widely expected to arrive in Sudan in mid-June. The United States Agency for International Development estimates that more than 9 million Sudanese will require humanitarian assistance this year.

On that same day in April, Khartoum’s political cliques were abuzz with rumours of a military coup. General Mohamed Hamdan Daglo – a paramilitary leader from Darfur known as Hemedti, who manoeuvred into the second-highest position in the state during the revolution – seized his opportunity to gain greater power. Playing on the fears of the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), a coalition of parties that backs the civilian government, he secured their approval to become the head of the Emergency Economic Committee – a powerful, if ad hoc, executive body. Hemedti promised to deposit $200m of his own money in the central bank to tackle the economic crisis. Hamdok would serve as his deputy on the committee.

This setup testified to the new realities of power in Sudan’s political transition. Despite the fact that a “constitutional declaration” places the civilian-dominated cabinet in charge of the country, the generals are largely calling the shots. They control the means of coercion and a tentacular network of parastatal companies, which capture much of Sudan’s wealth and consolidate their power at the expense of their civilian partners in government. For the activists who mobilised for radical change, this is a bitter pill to swallow. Many of them see Hamdok and his cabinet as puppets of the generals.

Democratic forces can still salvage Sudan’s transition, but Hamdok will need to show leadership and receive foreign backing. In particular, Hamdok will need to establish civilian authority over the parastatal companies controlled by the military and security sector. The task is daunting and fraught with risks, but Hamdok can acquire greater control by taking advantage of the rivalry between Hemedti and General Abdelfattah al-Buhran, the de facto head of state. He will need Europeans’ help if he is to succeed.

This paper shows how they can provide this help. It draws on 54 recent interviews with senior Sudanese politicians, cabinet advisers, party officials, journalists, former military officers, activists, and representatives of armed groups, as well as foreign diplomats, researchers, analysts, and officials from international institutions. The paper explores the international and domestic dynamics that account for the transition’s stalemate; analyses the balance of power in Khartoum and the influence of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia on the political process; and spells out the potential for further destabilisation. It also explores the consolidation of parastatal companies in the hands of the generals since the revolution; shows why establishing civilian control over these firms represents an urgent economic priority and a prerequisite for civilian rule; and lays out the ways Europeans can push in this direction.

Sudan’s chance for democratisation is the product of a difficult struggle against authoritarianism. For three decades, Bashir ruled as the president of a brutal government. He took power in 1989 as the military figurehead of a coup secretly planned by elements of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood, before pushing aside Islamist ideologue Hassan al-Turabi, who had masterminded the plot. During his rule, Bashir survived US sanctions, isolation from the West, several insurgencies, the secession of South Sudan, a series of economic crises, and arrest warrants from the International Criminal Court for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Darfur. He presided over ruthless counter-insurgency campaigns that deepened political rifts and destroyed the social fabric of peripheral regions such as Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile.

In the process, Bashir recruited a growing number of soldiers, spies, and militia fighters as he built new forces to hedge against the faltering loyalties of those he had come to rely on. He strengthened the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) – now known as the General Intelligence Service – to discourage a coup by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). Later, he turned pro-government tribal militias from Darfur into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), an organisation led by Hemedti, as insurance against threats from the NISS.

Throughout the 2010s, the Bashir regime put down successive waves of protests. But the uprising that began on December 2018 – triggered by Bashir’s decision to lift subsidies on bread – proved too much for the government to contain. As the movement grew, a coalition of trade unions called the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) established informal leadership of nationwide demonstrations, generating unprecedented unity among opposition forces. In January 2019, a motley coalition of armed groups, civil society organisations, and opposition parties united under a common declaration, marking the birth of the FFC. The protests culminated in April 2019 in a sit-in at the gates of the military headquarters in Khartoum. As junior officers vowed to protect demonstrators, the leaders of the military, the RSF, and the NISS put their mistrust of one another aside, overthrew Bashir, and installed a junta.

In the weeks that followed, the generals negotiated with the leaders of the FFC. Buoyed by regional backing, the generals resisted any concession that would have threatened their dominance.[1] But the demonstrators refused to back down. They demanded civilian rule and organised the complex logistics of a sustained sit-in. Over time, as it became clear that the generals had no intention of relinquishing power, the mood at the sit-in hardened. Many participants came to reject any form of military representation in transitional institutions.[2] On 3 June, the last day of Ramadan, the generals sent troops to crush the sit-in. RSF militiamen and policemen beat, raped, stabbed, and shot protesters, before throwing the bodies of many of their victims into the Nile. Around 120 people are thought to have been killed and approximately 900 wounded in the massacre.

These abuses prompted Washington and London to pressure Abu Dhabi and Riyadh to curb the abuses of their client junta, turning the tide in the negotiations. By late June, the generals and the FFC had agreed on the outline of a power-sharing agreement – even as a “march of the million” organised by grassroots organisations showed that the demonstrators had not been deterred. On 4 August, the generals and the FFC signed the constitutional declaration.

The document envisioned a transition that would – over the course of a little more than three years, and under the guidance of a civilian-led cabinet of ministers – reach a peace deal with armed groups from the peripheral regions of Sudan, while establishing a new constitutional order and free elections. A mixed civilian-military body known as the Sovereignty Council would serve as the head of state and exercise limited oversight, but the “supreme executive authority” would lie with the cabinet. General Abdelfattah al-Burhan, the head of the junta, would chair the Sovereignty Council – with Hemedti as his deputy – until May 2021, before handing the position over to a civilian. A Transitional Legislative Council would act as the parliament: enacting laws, overseeing the cabinet and the Sovereignty Council, and representing the country’s diverse groups.

When Hamdok, a UN economist picked by the FFC, took office on 21 August, there were grounds for cautious optimism. The peace talks with armed groups began in earnest and seemed to make rapid progress. Hamdok inherited a catastrophic economic situation and political structure in which the generals remained in high office but the constitutional declaration put civilians in the driving seat. Western countries expressed their full support for the transition. The journey would be difficult, but its direction was clear.

There is no doubt that Sudanese citizens have gained new civil and political rights since the transition began. The new authorities have curtailed censorship. The harassment and arbitrary, often violent detentions conducted by NISS officers have largely ended. Minorities such as Christians now have freedom of religion. The government has repealed the public order law, which allowed for public floggings. And it is in the process of criminalising female genital mutilation.

But the transition has otherwise stalled. Peace remains elusive. The peace talks have lost momentum after becoming mired in haggling over government positions. Most leaders of the armed groups that are negotiating with the authorities, gathered under the umbrella of the Sudan Revolutionary Front, represent narrow social bases. Many of their fighters are currently serving as mercenaries in the Libyan conflict. The two rebel factions that still control territory in Sudan are not actively participating in the talks. Meanwhile, localised violence has flared up in Darfur, eastern states, and South Kordofan.

The institutional agenda of the transition, designed to empower civilians, remains at a standstill. The Transitional Legislative Council, the new civilian governors, and the commission in charge of planning the constitutional conference have not been appointed. The authorities have not achieved much on transitional justice.[3] The head of the commission in charge of investigating the 3 June massacre of revolutionary demonstrators said he could not protect witnesses. The authorities said they are willing to cooperate with the International Criminal Court to try Bashir and the other wanted leaders, but the generals are blocking a handover of the suspects to The Hague.

And the economy continues to deteriorate. The predicament began with South Sudan’s secession in 2011. During the 2000s, when revenue from oil largely produced in the south flowed into Khartoum’s coffers, government spending grew by more than 600 percent. The secession cut off Khartoum’s access to most of these oil reserves, resulting in a collapse in revenue, a shortage of dollars, and a budgetary and foreign exchange crisis.

Bashir’s government responded by printing money to buy local commodities – mainly gold from the booming domestic mining sector – at international prices, before selling them on international markets. Through the scheme, the government acquired foreign currency to finance the import of commodities it subsidised – fuel, wheat, and medicine – but created a vicious spiral of monetisation and inflation. Despite these efforts, the authorities soon began to run out of foreign exchange reserves. By 2018, the authorities were struggling to finance imports, and queues were forming outside petrol stations. The economic slide continued, prompting Bashir’s downfall. It has only continued since then. The Sudanese pound, which traded at 89 to the dollar in the last weeks of Bashir’s rule, now trades at 147 to the dollar.

Hamdok planned to address the disastrous economic situation by mobilising international support. Hamdok also hoped that the goodwill resulting from regime change would bring Sudan a windfall in development assistance. And if the international community could fund, for a few years, a new social safety net – at the cost of $2 billion per year – the government would lift subsidies on fuel, then wheat. These would be the first steps towards the stabilisation of the deficit and of the currency.

In late 2019, Hamdok and Finance Minister Ibrahim al-Badawi set out on diplomatic visits to Washington and European capitals. They hoped to gain financial pledges and to persuade the US to remove Sudan from its list of state sponsors of terrorism. The designation, which forces the US to vote against debt relief for Sudan at the World Bank and the IMF, is a relic of the 1990s, when Bashir provided a safe haven to many jihadists, including Osama bin Laden. The rationale for the listing had already weakened by the 2000s because, in the wake of 9/11, the NISS started to share intelligence on terrorist threats with the CIA. The designation makes even less sense now that Bashir is gone.

Although the state sponsor of terrorism designation does not impose formal sanctions on Sudan, it sends a political signal that stigmatises the country, deters foreign investment and debt relief, and casts doubt on Washington’s claim to support civilian government. Unfortunately for Hamdok, Sudan does not sit high on the list of priorities of the current US administration. President Donald Trump decided not to fast-track Sudan’s removal from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, allowing the process to take the bureaucratic route and become enmeshed in the conflicting perspectives of the State Department, national security and defence agencies, and Congress.

Europeans have also pledged support to Sudan but have been slow to provide it, despite engaging in a flurry of diplomatic activity with Khartoum. Since Hamdok’s appointment, they have publicly and privately called on the US to lift its state sponsor of terrorism designation. The European Union has pledged €250m in new development assistance (along with €80m in support against covid-19) to Sudan, while Sweden has pledged €160m, Germany €80m, and France €16m-17m. Yet these are paltry figures in comparison to Europeans’ declared commitments.[4]

Given its crushing debts, Sudan seems unlikely to stabilise its economy without debt relief and new financing. In addition to the $2 billion per year required to fund its social safety net, Sudan needs an estimated $6 billion to stabilise the pound. The path to debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HPIC) Initiative is long in any circumstances. But US indifference, European timidity, and the indecisiveness of Hamdok’s cabinet have combined to kill off hopes that the diplomatic momentum Sudan established in September and October 2019 would quickly translate into substantial international assistance.

A US vote against debt relief for Sudan under the HPIC Initiative would only apply at the so-called “decision point”, which comes around a year into the process. In theory, this gives the Sudanese government and the IMF time to cooperate under the initiative as the US works to take Sudan off its list of state sponsors of terrorism. But international financial institutions will not provide new funding to Sudan before the country clears its debt arrears. Discussions between the IMF and the Sudanese government in late 2019 and early 2020 yielded nothing of substance: the government hesitated to commit to the structural reforms – starting with subsidy reforms – that the IMF requires to set up a Staff Monitoring Programme, a first step towards debt relief under the HPIC Initiative.

International financial institutions have also taken note of foreign powers’ lack of enthusiasm for Sudan.[5] In September 2019, at a meeting in Washington, IMF officials reportedly advised Badawi to hold off on subsidy reform until international donors committed to funding the new social safety net, which would cushion the blow.[6] The World Bank sought to raise money for a new multi-donor trust fund for Sudan in October and December 2019, but failed to secure a single pledge.[7]

The Friends of Sudan, an ad hoc group of donors and multilateral organisations established to coordinate international initiatives on the country, have inadvertently put this reluctance on display. Formed around a core group of actors that includes the US, the United Kingdom, Germany, the EU, France, and Norway, the body has since expanded to include the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Nations, and the African Union. Successive meetings in late 2019 and early 2020 have not led to substantive action. A pledging conference scheduled for June will be a crucial test of international goodwill. But Sudan’s international supporters have already lost precious time.

International donors blame their reluctance to assist the Sudanese government on its inaction regarding subsidy reform. In December, Badawi introduced a draft budget that envisioned a gradual removal of subsidies. But the leadership of the FFC – the nominally ruling coalition – opposed the policy, on the grounds that it would further increase the cost of living. Unwilling to move forward without FFC support, Hamdok agreed for the issue to be decided at a national economic conference scheduled for March 2020. The conference was later postponed until June 2020. Due to restrictions on meetings created by covid-19, it is now unclear whether the conference will take place at all.

Donors see a moral hazard in funding the government’s social safety net before it firmly commits to removing subsidies on fuel. They worry that, if they provide funds too early on, the government may spend the money while postponing reforms, eventually forcing them into an open-ended commitment to bankroll a social safety net that was designed to be temporary.

But the moral hazard goes both ways. Donors want the Sudanese government to commit to reforms that will have a social cost in return for a promise of unspecified levels of funding. The pledges Sudan receives in June could fall far below the estimated $1.9 billion the government needs, forcing the authorities to create the social safety net only gradually.[8] This would go against the logic of a temporary programme designed to offset one-off price hikes. In these conditions, subsidy reform – however necessary – is a gamble for the government.

Subsidies on fuel, wheat, and medication cost the government an estimated $4 billion annually, or around 12 percent of GDP. This amount is equivalent to the government deficit, or 38 percent of the budget.[9] Because they are financed by monetisation, the subsidies have the tendency to grow at a compound rate. In the words of US Special Envoy for Sudan Donald Booth, the measures are “untargeted” and “unsustainable”.[10]

The reform is a thorny domestic issue, since Bashir’s attempt to cut subsidies triggered the revolution. The issue has an immediate impact on the lives of many Sudanese and resonates with the communist, Nasserist, and Ba’athist ideological commitments of the older members of the FFC leadership, who dominate decision-making within the coalition.

The concerns over the social impact of subsidy reform are warranted. Prior to the collapse of oil prices this year, the IMF estimated that the reform would increase gasoline prices by an average of 44-70 percent per year over the next six years. There is no publicly available analysis of the possible knock-on effects of this rise on aggregate demand; on the price of basic commodities that rely on fuel for their production, such as agricultural products; or on the water supply in areas that rely on gasoline pumps. Aware of the risks, the IMF – in contrast to donors – argues that “an expanded social safety needs to be in place prior to the implementation of potentially disruptive subsidy and exchange rate reform”.

Many in the FFC leadership are pushing for other measures. These include the recovery of assets captured by Bashir’s regime; a rise in taxes on, for instance, luxury goods; and the establishment of civilian control over military and security companies.[11] Al-Tijani Hussein, a leading member of the FFC’s economic committee, denounced Badawi’s policies as “ready-made prescriptions … by the IMF”.

There are progressive arguments in favour of subsidy reform. The current system helps create a highly organised black market that siphons off anywhere between 20 percent and 80 percent of subsidised goods – thereby taking colossal amounts of money out of public coffers without providing any social benefits.[12] Fuel is mostly consumed by the middle and upper classes, in a country where few people own vehicles. Subsidies on bread favour relatively well-off urban dwellers over rural people, whose staples are sorghum and millet. And, of course, the deficit created by the subsidy budget is now so large that it prevents the government from improving social services.

Given that the subsidy crisis puts the transition at risk, both the Sudanese government and international donors should realise that they have a vested interest in looking beyond their short-term concerns and overcoming this problem of coordination. There have recently been some signs of progress. The cabinet has signalled that it is ready to move ahead with subsidy reform. On 11 May, the government finally lodged a request for a Staff Monitoring Programme with the IMF. Badawi announced on 14 May the launch of the social safety net, renamed the “family assistance programme”. He talked about “better managing” subsidies. The government has, in practice, begun to liberalise fuel prices by restricting the distribution of subsidised fuel to 20 percent of the country’s petrol stations.[13] The collapse of oil prices this year will ease the process. Commercial prices are, in any event, already a reality at many petrol stations across the country: trucks carrying subsidised petrol that, under Bashir, were strictly controlled by the NISS are now typically diverted to the black market after they leave Khartoum.[14]

There are also signs that the leadership of the FFC is reconsidering its opposition to subsidy reform, and that the organisation could reach an agreement with the government on the issue before the national economic conference in June.[15] But, if Hamdok’s team fails to convince the FFC to go along before the donors’ pledging conference later that month – or if the deal comes too late for the cabinet to prepare a plan that will satisfy international donors – foreign aid to Sudan is likely to remain far below what Sudan needs. This would only deepen Sudan’s political and economic crisis.

Failure to stabilise Sudan’s economy would have far-reaching consequences for not only the country but also the wider region. Since Hamdok’s appointment, the domestic balance of power has once again tilted in favour of the generals, who could seize on the climate of crisis to restore military rule. If they remove civilian leaders from the equation, rival factions within the military and security apparatus will be set on a collision course.

The members of the FFC are much weaker today than they were a year ago. The revolutionary coalition has disintegrated under the weight of partisan jockeying for power. A narrow, quarrelsome group of party leaders from Khartoum has come to dominate the leadership of the FFC, excluding other components of the alliance. They have bickered over government positions and stymied, rather than pushed, the transition agenda.

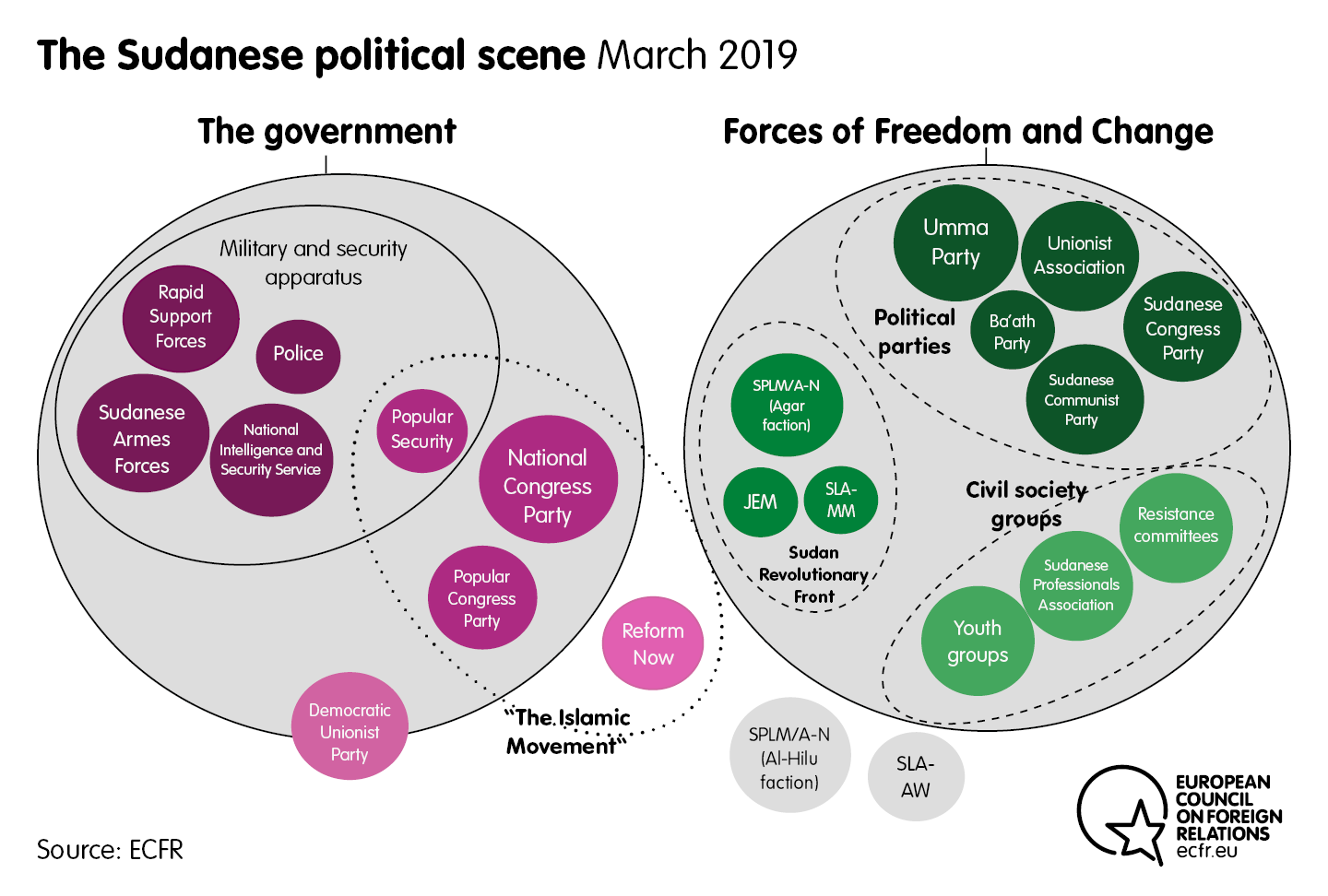

At its inception in January 2019, the FFC represented three groups. The first comprised the political parties that opposed Bashir, and whose leaders hailed from the socio-cultural elites of the central regions that have dominated the country since independence. The second was made up of armed groups from the peripheral regions, which have traditionally been marginalised. The third comprised diverse civil society organisations, such as the SPA, human rights groups, and so-called “resistance committees” – informal neighbourhood groups that emerged during the uprising to mobilise revolutionaries.

By April 2019, political parties and the SPA had come to dominate the FFC team that negotiated with the junta, excluding representatives of armed groups and most civil society organisations. In August, Sudan’s political parties signed the constitutional declaration without consulting armed groups, prompting a de facto divorce between them. Many civil society organisations also complained about their exclusion from the process. By the end of 2019, the SPA and resistance committees had been infiltrated from all sides and their influence had waned considerably. The remainder of the FFC was dominated by the Umma Party – a large, if declining, organisation that mobilised on the basis of traditional religious loyalties – the Sudanese Communist Party; a handful of smaller left-leaning groups, such as the Sudan Congress Party; and tiny Ba’athist and Nasserist factions that had acquired an outsized role through agile political manoeuvres. This rump coalition further broke down in April and May, when the Umma Party suspended its participation in the FFC’s ruling bodies, and the Sudan Congress Party called for the resignation of ministers and civilian members of the Sovereignty Council. At the time of writing, the FFC had, in practice, shrunk to encompass the Communist Party, the Sudan Congress Party, the SPA, the Unionist Association, the Ba’ath party, and a smattering of individuals – none of which could claim to have a broad popular base.

Within the government, the configuration of power that has emerged since September 2019 bears little resemblance to the delicate institutional balance – enshrined in the constitutional declaration – that the FFC fought so hard to achieve in its negotiations with the junta.

The generals seized executive authority for the Sovereignty Council and, by extension, themselves. Burhan, who is the top general in the Sudanese military, and his deputy on the council, Hemedti, allowed Hamdok to woo the West and mediate delicate talks between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. But, otherwise, the generals have been calling the shots on crucial foreign affairs and domestic issues.

In January, after Hamdok asked the Security Council to launch a new UN mission in Sudan, the Sovereignty Council forced him to backtrack. In February, he sent a letter that scrapped any reference to giving the mission a mandate to monitor and report on security sector reform and the implementation of the constitutional declaration. The two projects directly threatened the interests of the generals (the constitutional declaration bans members from the Sovereignty Council from running in future elections).

The generals’ influence is also visible in domestic decision-making. Hemedti initiated peace negotiations with rebel groups, initially bypassing the civilian government and the FFC. Burhan appointed and chairs a Joint Defence and Security Council, in which civilian members of the cabinet are a minority. Members of the Sovereignty Council also chair other ad hoc, tripartite committees that de facto make policy, such as those on the coronavirus, the fight against corruption, and the economic emergency.

The generals’ public relations machine is now well-oiled. The military opened a bakery in Atbara, the cradle of the 2018-2019 uprising. Hemedti has established health clinics and a fund to support farmers; his forces have distributed RSF-branded food supplies and launched a mosquito-eradication campaign.

Meanwhile, Hamdok has not proven to be the leader some hoped for. Rather than use his position to drive the transition, he has sought consensus – refraining from making any decision without a green light from the FFC, the generals, or both. For instance, he has chosen not to exercise his power to replace military state governors from the Bashir era with civilian leaders, as he disapproves of those nominated by the FFC. He has also prioritised good relations with the generals, referring to “a partnership [between them that] is working” even as his power steadily declines. “Hemedti sees [Hamdok] as a clerk”, said one person who regularly speaks with the paramilitary leader.[16]

As a result, the thematic committees – which include members of the Sovereignty Council, the FFC, and the cabinet – have become the new locus of decision-making. Since it gained influence over policy through these opaque mechanisms, the FFC’s narrow leadership appears to have had little enthusiasm for establishing the Transitional Legislative Council, even though this interim parliament would be a crucial tool for holding the Sovereignty Council and the cabinet to account.

But this arrangement is unstable. Neither Hamdok nor the FFC has attempted to mobilise public support when faced with obstruction by, or resistance from, the generals. As such, they have given up one of the few cards they held and created the impression that they have been co-opted by the old regime. The popularity of the FFC has collapsed; Hamdok earned considerable goodwill with the Sudanese public in late 2019, but their patience with him is wearing thin. Many activists say that they would be back on the streets if it were not for covid-19 (which has so far had a limited health impact on Sudan but, as elsewhere, led to restrictions on public gatherings).

Having forsaken the agenda to build strong institutions that could shape the national political process, Hamdok and the FFC have perpetuated Sudan’s traditionally informal politics. This puts the generals – who control the money and the means of coercion – at an advantage. When the next political crisis comes, no institution will stand in the way of a potential power grab.

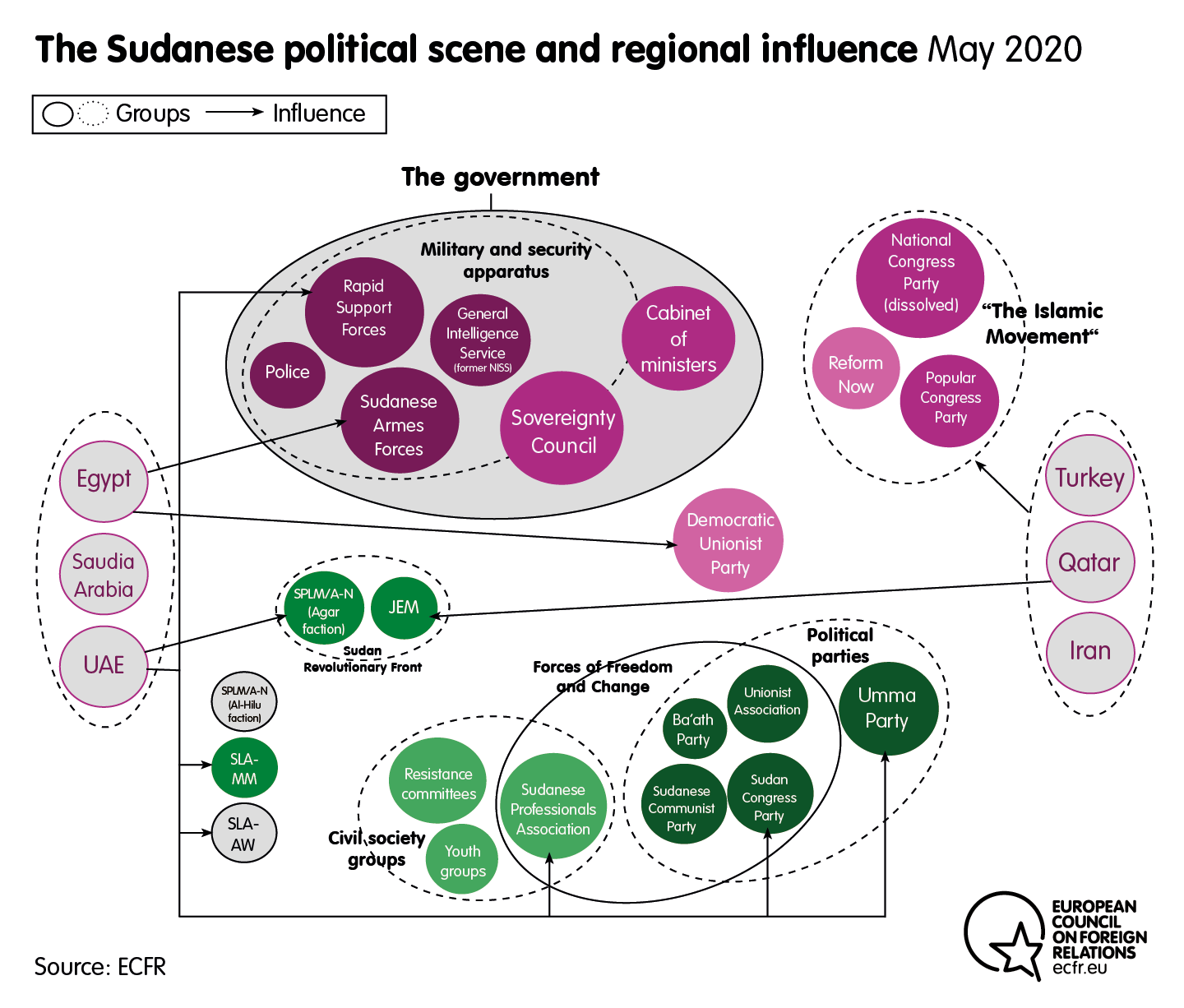

These developments have unfolded under the influence of regional powers, which has reached a scale unprecedented in Sudan’s recent history. The so-called “Arab troika” of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt have taken advantage of the revolution to sideline their regional rivals Turkey and Qatar, which had long supported Bashir’s regime. The Emiratis, in cooperation with the Saudis, are playing a particularly active role in shaping Sudan’s political process, reportedly spending lavishly and manoeuvring to position Hemedti as the most powerful man in the new Sudan despite intense resistance from the SAF.

The troika saw the revolutionary uprising of 2018-2019 as an opportunity. Having lost patience with Bashir, who had sought their support but played them off against Qatar and Turkey, the troika believed they had a chance to depose Bashir and establish a closer relationship with the Sudanese government. The UAE approached the political opposition and armed groups in February 2019, at the height of the uprising, to probe their willingness to support regime change.[17] Around the same time, the head of the NISS, Salah Gosh, secretly visited prominent political prisoners in jail and, with Emirati backing, reportedly offered Bashir an exit plan (which he rejected).

When the generals overthrew Bashir in April, Sudan’s neighbours – Egypt, Chad, South Sudan, Eritrea, and, initially, Ethiopia – converged with Saudi Arabia and the UAE to support the new junta against the demands of revolutionary demonstrators.[18] Riyadh and Abu Dhabi promised $3 billion in support to the generals. The Emiratis provided advisers and weapons to Hemedti, angering the SAF.[19]

Emirati influence has pervaded Sudan’s politics ever since. After returning from trips to Abu Dhabi, representatives of influential FFC parties and armed groups took stances favourable to the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Hemedti. The Emiratis are widely known to be generous with their covert financial contributions, which flow either directly to various political actors or, indirectly, through Hemedti.[20] Mohammed Dahlan, the Palestinian exile who runs many important security projects on behalf of Emirati ruler Mohammed bin Zayed, handles the UAE’s Sudan file.[21] Former Sudanese general Abdelghaffar al-Sharif, once widely considered the most powerful man in the NISS, reportedly lives in Abu Dhabi and has put his formidable intelligence network at the service of the UAE.[22]

The Arab troika has also worked to undermine Hamdok and prop up the generals. For instance, the UAE facilitated a secret meeting between Burhan and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, as well as direct communication between Burhan and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. The move bypassed Hamdok, undermined the State Department’s policy of support for civilian rule, and positioned Burhan to reap the political benefits of a potential repeal of the state sponsor of terrorism designation.[23] The UAE also provided financial support to the Sudanese government’s peace talks with armed groups. This gave Hemedti and General Shamseddine al-Kabbashi, another prominent member of the Sovereignty Council, an opportunity to appear to be peacemakers.[24] Burhan and Hemedti have recently visited Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, and Cairo – sometimes alone; sometimes with Hamdok.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the policy of the UAE and Saudi Arabia lies in the ways in which they have directed their financial flows, doling out funds or cutting support to gain political leverage. The countries quietly ended their support to the government in December 2019, having disbursed only half of the $3 billion they pledged to it in April 2019.[25] The move appeared to mirror the UAE’s decisions to stop assistance to Bashir in December 2018 – which contributed to his downfall – and to offer support to new rulers more aligned with Emirati preferences. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have avoided financing transparent mechanisms such as the World Bank’s Multi-Donor Trust Fund. Meanwhile, Hemedti appears to have a large supply of cash with which to support the central bank. In March, he deposited $170m in the bank. These developments suggest that the Gulf powers could be using their financial might to shape the outcome of Sudan’s domestic political process, redirecting flows of money to prop up Hemedti and exacerbating the economic crisis to position him as a saviour.

Sudan’s current trajectory should be a cause for serious concern among European policymakers. The democratic transition is vulnerable to shifts in the balance of power between Burhan, Hemedti, Hamdok’s cabinet, and the FFC. Due to the extreme fragmentation of Sudanese politics and the lack of constitutional safeguards, Sudan’s fate is more uncertain than it has been for decades. And the situation is likely to deteriorate in the coming year. Credible scenarios include another mass uprising; a slow-burn economic and state collapse caused by political deadlock; Burhan’s refusal to step down as president of the Sovereignty Council in 2021; a move by the generals to replace the FFC with pliable civilian figureheads, ahead of a snap election; a fully fledged military takeover; and a civil war resulting from a botched coup attempt or the escalation of conflict between the SAF and the RSF.

Tension between former members of the Bashir regime may be the most serious threat to the future of the state. Bashir’s rule rested on four pillars: the National Congress Party (NCP) – an offshoot of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood – the SAF, the NISS, and the RSF. The subsequent emergence of Burhan and Hemedti as the new leaders of the junta marginalised the NCP, which the authorities dissolved in November 2019, and the NISS.

The SAF and the RSF make for awkward bedfellows. The alliance was born in April 2019, when the defection of low-ranking SAF officers forced military and security leaders to oust Bashir to avoid violence between rebels and loyalists. Since then, the SAF-RSF alliance has centred on personal ties between Burhan and Hemedti, forged during their time in Yemen, when they commanded Sudanese troops deployed in support of a coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. But, Burhan aside, SAF officers’ resentment of Hemedti runs deep. Because he comes from Darfur and heads a paramilitary group, his newfound prominence challenges the supremacy of top officers, who are overwhelmingly from Sudan’s central regions. Officers in the lower ranks resent the RSF’s role in the 3 June massacre.[26]

Burhan and Hemedti are competing behind the scenes for access to resources, such as the formidable NISS intelligence network. The RSF has poached SAF officers by offering them better pay. The rivalry remains in check – for now – partly due to the presence of Hamdok and the FFC, which complicates the strategic calculations of the SAF and the RSF while preventing the emergence of a single political fault line centred on the military and security apparatus.

In addition, in the past few months, Hemedti and many in the FFC have come to fear that a coalition of former leaders of the NCP, NISS officers, and Islamist officers within the SAF will try to seize power, either by destabilising the country as a prelude to a coup, by assassinating Burhan or Hemedti, or both.[27]

Fears of Islamist destabilisation have been rife since the revolution, but it is difficult to assess the threat that former NCP leaders pose. The party established a clandestine security structure made up of loyalists, the Popular Security, which pervaded all state institutions. Most NISS officers under Bashir were loyal to NCP leaders; within the SAF, those who pledged a vow of allegiance to the party reportedly amounted to about 30 percent of the officer corps, but they were well organised.[28] Now that many top NCP officials are in jail and that the realities of power have changed, it is unclear how relevant these past affiliations still are. Some General Intelligence Service officers, for instance, are now loyal to Hemedti.[29] Widespread public hostility to political Islam since the revolution would also make an Islamist takeover difficult.

Nonetheless, several recent events have stoked these fears. Burhan sought to remove a prominent FFC member of the anti-corruption committee who has been spearheading the recovery of assets from former NCP leaders. He is also reportedly communicating with Ali Karti, a prominent former leader of the NCP who is now in hiding. This has heightened Hemedti’s suspicions.[30] Prominent Islamists have openly incited attacks on Hemedti and Hamdok. In March, a home-made bomb damaged Hamdok’s convoy in Khartoum. These events have brought the FFC and Hemedti closer together since April. Some FFC leaders see Hemedti as a protector – in the short term, at least – because, while he is a war criminal, he is no Islamist.[31]

The tension between Sudanese leaders grew in May, when outbreaks of localised violence engulfed South Darfur, as well as Kassala, a major city in the east, and Kadugli, the capital of South Kordofan. In most cases, the incidents resulted from the escalation of tension between local communities. But their scale and simultaneity, and the lack of response from the local authorities, led many to believe that the attacks were part of a coordinated attempt to destabilise Sudan. Regardless of whether this is the case, such suspicion is enough to increase tension. In Kadugli, an SAF unit made up of Nuba fighters killed nine people in an attack on the RSF, which in the area largely recruits from local, Arabised pastoralist communities. On 13 May, Hemedti accused unknown forces of trying to “draw the RSF into a civil war through a collision with the military and by taking [the organisation] out of Khartoum”. The levels of resentment between the RSF and SAF are such that many officers fear a local incident could escalate into broader clashes between the two forces.[32]

To reverse these trends, Hamdok and the FFC need to urgently work to shift the balance of power away from the generals. A strong civilian component in the government would counterbalance the military and security apparatus, ease the rivalry between the SAF and the RSF, and increase the likelihood that the transition will succeed.

This will not be easy to achieve. It will require the FFC and Hamdok to proceed with the implementation of the constitutional declaration, including the much-delayed appointments of the Transitional Legislative Council and civilian governors, as preludes to the constitutional conference and free elections.

It will also require economic stabilisation. Beyond subsidies, the economic debate in Sudan has recently turned to the issue of how the civilian authorities can acquire greater revenue – particularly by recovering assets stolen by the Bashir regime, and by gaining control of the sprawling network of parastatal companies affiliated with the military and security sector.

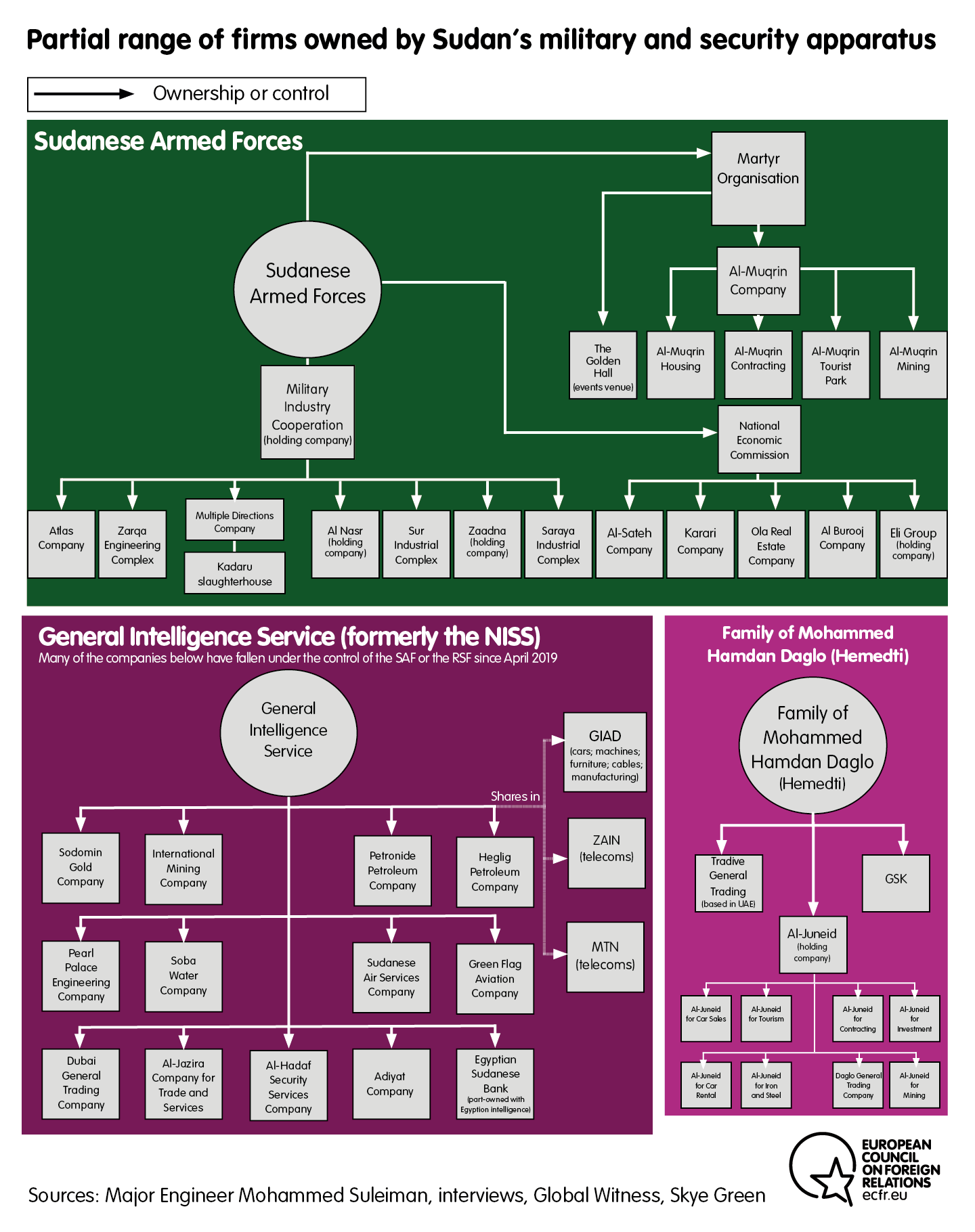

Sudan has a tax burden of around 5 percent of GDP, one of the lowest in the world. The IMF emphasises that revenue mobilisation should be an urgent priority for the government. It is not difficult to identify who to tax: companies owned by NCP businessmen, Bashir’s family, the SAF, the NISS, and the RSF play a dominant role in the economy, yet benefit from generous tariff and tax exemptions. They are everywhere one looks.

An anti-corruption government committee led by determined figures from the FFC said it had recovered between $1.06 billion and $3.5 billion in assets, most of them from NCP leaders and their cronies. Billions of dollars in stolen funds are said to be stashed in the UAE, the UK, and Malaysia. For instance, former International Criminal Court prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo estimated in 2010 that Bashir held $9 billion in UK banks. Low-profile legal proceedings to recover these funds are under way.

Companies owned by the NISS, Bashir’s relatives, and NCP figures are coveted prizes for Burhan and Hemedti, who compete for control of the firms’ resources. Burhan has put the Military Industry Corporation – an SAF holding company that owns hundreds of firms – in charge of many of the companies once owned by NCP leaders and Bashir’s family, while the RSF has gained control of many of the businesses previously run by the NISS.[33] In addition, the military now retains the profits of SAF companies that, under the previous regime, were largely channelled to the NCP.

Today, the military and security apparatus has shares in, or owns, companies involved in the production and export of gold, oil, gum arabic, sesame, and weapons; the import of fuel, wheat, and cars; telecommunications; banking; water distribution; contracting; construction; real estate development; aviation; trucking; limousine services; and the management of tourist parks and events venues. Defence companies manufacture air conditioners, water pipes, pharmaceuticals, cleaning products, and textiles. They operate marble quarries, leather tanneries, and slaughterhouses. Even the firm that produces Sudan’s banknotes is under the control of the security sector.[34]

Because they are central actors in the markets for fuel and wheat imports, companies owned by the SAF and the RSF benefit directly from subsidies on these commodities (and are well positioned to gain further profits by diverting them onto the black market). For instance, SIN, a firm which was formerly owned by the NISS and which Burhan recently brought under the exclusive authority of the SAF, reportedly controls 60 percent of the wheat market.[35]

Since the revolution, Burhan has appointed loyalists to manage many military-controlled companies. General Al-Mirghani Idris, a friend of Burhan’s from his time at the Military College, is now the head of the Military Industry Corporation. General Abbas Abdelaziz – a former head of the RSF who is also a close friend of Burhan – is now in charge of Al-Sati, another holding firm. Another former classmate, General Mohalab Hassan Ahmed, became the head of the Martyrs’ Organisation, a holding firm that previously funded the NCP, and that has investments in gold mining and entertainment venues.[36] The need to ensure that these companies make a profit appears to have encouraged Burhan – who initially purged many prominent Islamist officers from the ranks of the SAF and the NISS – to bring some his loyal friends out of retirement.[37]

Until recently, the RSF focused its commercial activities on the gold market, which it largely controls, as well as on construction, contracting, and human trafficking. But the RSF has expanded its economic activities in the past year. The organisation is using the hard currency it earns from gold sales in Dubai to buy agricultural projects and real estate. In one recent purchase, the RSF reportedly acquired 200,000 acres of agricultural land in Northern state; the project involves digging an irrigation canal to the Nile.[38]

These companies are shrouded in secrecy; high-level corruption and conflicts of interest make the boundaries between private and public funds porous. Hemedti, for instance, no longer has any official involvement in Al-Juneid, the holding company run by his brother, Abdelrahim Daglo. It is unclear whether Al-Juneid’s profits finance the RSF’s operations,[39] though some sources believe the business falls under the organisation’s special operations branch.[40] Military companies, on the other hand, belong to the Sudanese state but their management positions provide lucrative opportunities for embezzlement, which means that appointments form part of a system of rewards for loyalty.[41]

Although it is hard to estimate these companies’ profits, occasional glimpses into their activities show that that they have access to considerable amounts of cash. Al-Juneid, a company founded by Hemedti, sold around 1 tonne of gold in Dubai, worth roughly $30m, during a four-week period in 2018 – a figure that suggests an annual turnover of $390m. In May, the Multiple Directions Company, a subsidiary of the Military Industry Corporation, inaugurated with great fanfare the Kadaru industrial slaughterhouse – an investment worth $40m, whose first shipment went to Saudi Arabia. Hemedti is currently building a slaughterhouse on the same scale north of Khartoum.

Hamdok’s government has neither control over these firms nor access to their books. On 14 May 2020, Badawi acknowledged that none of the profits from the Kadaru slaughterhouse’s exports would go to the Ministry of Finance.

The generals are using dark money to keep the civilian government on life support, ensuring that it remains dependent on them. After promising to contribute $2bn to the government’s budget for 2020, the SAF arbitrarily reduced the figure to $1bn, blaming the economic downturn caused by covid-19.[42] The Military Industry Corporation reportedly plugged a $70m hole in the civilian government’s budget after Hamdok agreed on a settlement with the victims of the October 2000 bombing of the USS Cole – which US courts found the Sudanese state to have been responsible for – as part of an effort to remove Sudan from the state sponsors of terrorism list.[43] Hemedti has made a show of transferring his concession in Jebel Amer, Darfur’s largest gold mine, to the government, but the value of the facility is unclear.[44] And his contributions to the central bank have been crucial in positioning him as the head of the emergency economic committee.

The civilian government’s financial dependence on the generals creates an asymmetry of power that makes it difficult for the cabinet to be assertive on non-financial issues. Beyond its obvious fiscal benefits, civilian control of parastatal firms is a prerequisite of civilian rule. It would also ease a major concern of international donors (albeit one they are reluctant to acknowledge publicly): that development assistance to Sudan merely enables the military and security sector to avoid doing its share to fix Sudan’s devastated economy. By gaining control of parastatal companies, the civilian government could convince these donors that Sudan is engaged in substantive reform.

Badawi claims that the government has started a comprehensive review of the companies owned by the military, with the objective of putting all those involved in sectors unrelated to defence under the authority of the Ministry of Finance.[45] The SAF has formally agreed to cooperate with the process but, in practice, is not sharing the relevant financial data with the ministry.[46] Nonetheless, instead of calling for greater transparency and cooperation, Badawi has publicly defended the military and justified its actions.

The public discussion of the wealth of these companies is a positive development in itself. But meetings between the minister of finance and the generals behind closed doors are unlikely to produce results. Hamdok needs to become visibly involved in the issue, by drawing public attention to the important tasks of increasing government revenue and ensuring transparency in public finances. To this end, he could set up a committee comprising influential civil society figures – many of whom are currently outside government – and retired military officers who are known for their independence. He should state explicitly that the cabinet wants civilians to be appointed to management positions in companies involved in non-defence businesses. Hamdok can subtly exploit the rivalry between Burhan and Hemedti, each of whom has an interest in preventing the other from becoming any richer.

Following decades of consolidated authoritarianism, Sudan has entered a rare period of instability in its balance of power. Neither Burhan, Hemedti, Hamdok, nor the FFC can currently hope to rule without the support of some of the others. They all perform a kind of high-wire act as they contend with the influence of multiple regional powers and domestic groups within a highly fragmented political environment. This period is fraught with risks, but its volatility creates opportunities for radical change.

The US, Europe, and international financial institutions have left Sudan to its own devices, allowing its economy to tank and its political transition to stall. In the interim, the generals have expanded their reach and FFC leaders have returned to Sudan’s traditional elite bargaining, at the expense of institutional reform. Western inaction has also enabled regional actors – chief among them Abu Dhabi and Riyadh – to play a prominent role in Sudan, dragging the country closer to military rule or a civil war. Without a major course correction, Sudan is likely to enter a dark era.

European countries should increase their support for the civilian government. Most obviously, they should do so through a considerable increase in funding for projects that allow Hamdok and his cabinet to show the public that they can improve the lives of ordinary Sudanese. Such assistance will lend Europeans the legitimacy to push Hamdok and the FFC to proceed with the long-delayed but crucial appointments of the Transitional Legislative Council and new civilian governors.

However, this will not be enough in itself. Hamdok’s cabinet also needs to stand up for civilian rule and establish control over companies currently run by the military and the security services. The project poses a major risk for him. If he pushes hard, the generals may unite against civilian leaders. But there is no other way. In the words of one diplomat: “Sudan will never get itself on the path to debt relief if it doesn’t put order in the illicit economy”.[47] This is why the foreign actors who are influential in Sudan need to back the project.

Europeans should use their privileged relationship with Hamdok to convince him – and the generals – to address international donors’ concerns about the opacity of public finances and the civilian government’s problems with revenue mobilisation. Both issues are major obstacles to international financial support.

Europeans will need to enlist the support of the UAE and Saudi Arabia if they are to ensure that the generals cooperate with Hamdok. This will be a crucial test of the two Gulf countries’ commitment to a transition they helped broker. Across the region, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have demonstrated their preference for military governments over civilian-led democracies. Their recent actions in Sudan suggest that they may hope to repeat their success in helping return the military to power in Egypt in 2013. But this would be both cynical and naïve. A strong civilian component in the government is a prerequisite for stability in Sudan. The country’s conflicts are a direct result of state weakness – a weakness that pushed Bashir’s military government to use undisciplined militias to repress citizens, fuelling cycles of instability and the emergence of a fragmented military and security apparatus. In the current political environment, any attempt to formally impose military rule could ignite further instability and even a civil war. The UAE and Saudi Arabia showed last year that their fear of a destabilising escalation – combined with coordinated Western influence – could compel them to pressure the generals and grant more space to civilian leaders.

Europe should also try to show the UAE and Saudi Arabia that their economic interests in Sudan would be better protected by competent civilian rulers than by the generals. Sudan’s current predicament is the culmination of decades of economic mismanagement by a kleptocratic military government. The UAE and Saudi Arabia sunk billions of dollars in direct assistance into the central bank under Bashir, to no avail. The economic downturn associated with covid-19, which sets unprecedented constraints on the spending of the Emiratis and the Saudis, may help convince them that Sudan needs sound economic management. Their current and future investments in Sudan will be worth little if the country drifts into hyperinflation and chaos.

But EU member states are only beginning to discuss these issues with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, whose privileged partners on Sudan have been the UK and the US. In addition, these conversations occur at too low a level to prompt a shift in Riyadh or Abu Dhabi. To explicitly convey this message to the UAE and Saudi Arabia, EU countries should launch a joint effort at the ministerial level – with the backing of the US, the UK, and Norway, if possible. They should support Hamdok politically by publicly stating their commitment to his efforts to mobilise revenue streams currently controlled by the military and security sector, while providing him with private guarantees of support in the event of a crisis involving the generals. They should do this now – before it is too late.

Dr Jean-Baptiste Gallopin was a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, based in Berlin. Gallopin has been following Sudanese affairs since 2010 in various capacities, including as the Sudan researcher for Amnesty International, as a political analyst for a risk advisory firm, and as an independent consultant. His co-authored report for Amnesty, entitled “We Had No Time to Bury Them – War Crimes in Sudan’s Blue Nile State” was the first to document war crimes and potential crimes against humanity in the Blue Nile conflict.

Gallopin has published in Le Monde Diplomatique, the Washington Post, Democracy & Security, Aeon, Libération, Le Figaro, and Jadaliyya. He regularly appears as a commentator on international media, including Al Jazeera English, RFI, France 24, Deutsche Welle, and Bloomberg. In addition to his PhD, he holds a MA and a MPhil in Sociology from Yale, a MA in Arab Studies from Georgetown University, and a BA in Politics from Sciences Po Lyon.

Jean Baptiste Gallopin is no longer a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

[1] Interview with a diplomat in Khartoum, April 2019.

[2] Author’s interviews at the sit-in, April and May 2019.

[3] Interview with a Washington-based analyst, March 2020.

[4] Interview with a European diplomat, April 2020; interview with EU staff, May 2020.

[5] Interview with an EU official, May 2020.

[6] Interview with a Sudanese cabinet adviser, May 2020.

[7] Interview with a World Bank employee, April 2020; with a Sudanese cabinet adviser, May 2020.

[8] Interview with a World Bank official, May 2020. The author would like to thank Gerrit Kurtz for the latter observation.

[9] Interview with a US diplomat, March 2020.

[10] Columbia University panel featuring Donald Booth, 24 April 2020.

[11] Interview with an official from the Sudanese Communist Party, April 2020.

[12] Interview with a US diplomat, March 2020.

[13] Interview given by Ibrahim al-Badawi to Sudanese newspaper At-Tayyar, 14 May 2020.

[14] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[15] Interview with a cabinet adviser and with an official of the Umma party, May 2020.

[16] Author’s interview, May 2020.

[17] Interview with a senior officer of an armed group in the Sudan Revolutionary Front, March 2020; interview with a Sudanese activist, April 2020.

[18] Interview with a diplomat, Khartoum, April 2019.

[19] Interview with a diplomat, Khartoum, April 2019.

[20] Interview with a member of an armed group, March 2020; with a Sudanese journalist, March 2020; with a regular interlocutor of Hemedti, May 2020.

[21] Interview with a Gulf analyst, April 2020.

[22] Interview with a member of an armed group, March 2020; interview with a Sudanese journalist, April 2020.

[23] Interview with a Washington-based analyst of US foreign policy, February 2020.

[24] Interview with an international observer of the talks, February 2020.

[25] Interview with a European diplomat, May 2020.

[26] Interview with an SAF officer, Khartoum, April 2019; interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[27] Interview with a Sudanese journalist, May 2020; interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[28] Interview with a Sudanese journalist, April 2020.

[29] Interview with an international researcher, June 2020.

[30] Interview with a Sudanese journalist, May 2020; interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[31] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[32] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[33] Interviews with former SAF officers, May 2020.

[34] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[35] Interview with former SAF officers, May 2020.

[36] Interview with former SAF officers, May 2020.

[37] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[38] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[39] Interview with an international researcher, June 2020.

[40] Skye Green, “The RSF Empire: An in-depth Analysis into the Rapid Support Forces of Sudan”, December 2019.

[41] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[42] Interview given by Ibrahim al-Badawi to Sudanese newspaper At-Tayyar, 14 May 2020.

[43] Interview with a former SAF officer, May 2020.

[44] Interview with a cabinet adviser, May 2020.

[45] Interview given by Ibrahim al-Badawi to Sudanese newspaper At-Tayyar, 14 May 2020.

[46] Interview with a cabinet adviser, May 2020.

[47] Interview with a diplomat, May 2020.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.

We will store your email address and gather analytics on how you interact with our mailings. You can unsubscribe or opt-out at any time. Find out more in our privacy notice.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. You can revoke or adjust your selection at any time under Settings.

Accept all

Save

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Back

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information