The Mahdist Revolution was an Islamic revolt against the Egyptian government in the Sudan. An apocalyptic branch of Islam, Mahdism incorporated the idea of a golden age in which the Mahdi, translated as “the guided one,” would restore the glory of Islam to the earth.

Attempting to overhaul Egypt through an aggressive westernization campaign, Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali, who was himself a provincial governor of the Ottoman Empire, invaded the Sudan in 1820. Within a year his armies had subdued the Sudan and he began conscripting local Sudanese men into the Egyptian military. In 1822 Khartoum became the capital of Egyptian-occupied Sudan and a distant outpost in the Ottoman Empire.

Egyptian rule over the Sudan involved the imposition of high rates of taxation, the taking of slaves from the local population at will, and the absolute control over all Sudanese trade which destroyed livelihoods and indigenous practices. During the process of military conscription, tens of thousands of Sudanese men and boys died on their long march from the Sudanese hinterlands to Aswan, Egypt.

Ali’s tenure as Egyptian governor ended in 1848, but the suffering of the Sudanese people under Ottoman rule did not. When the anti-slavery campaign of the new Egyptian governor, Ismail, began in 1863, Sudanese unrest intensified since human bondage was now an integral part of the local economy. Matters were complicated by the arrival of the British in 1873 who assumed responsibility over Egypt in order to protect their interests in the Suez Canal and ensure repayment of loans to that government. General Charles Gordon was appointed governor of Sudan and he immediately intensified the anti-slavery campaign initiated a decade earlier. Sudanese Arab leaders, however, saw British efforts as a European Christian attempt to undermine Muslim Arab dominance in the region.

On June 29, 1881, a Sudanese Islamic cleric, Muhammad Ahmad, proclaimed himself the Mahdi. Playing into decades of disenchantment over Egyptian rule and new resentment against the British, Ahmad immediately transformed an incipient political movement into a fundamentally religious one. Urging jihad or “holy war” against imperial Egypt, Ahmad formed an army.

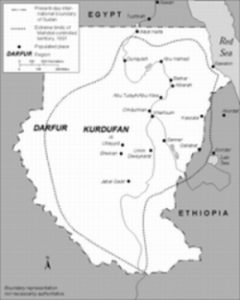

By 1882 the Mahdist Army had taken complete control over the area surrounding Khartoum. Then, in 1883, a joint British-Egyptian military expedition under the command of British Colonel William Hicks launched a counterattack against the Mahdists. Hicks was soon killed and the British decided to evacuate the Sudan. Fighting continued however and the British-Egyptian forces which defended Khartoum in a long siege were finally overrun on January 28, 1885. Virtually the entire garrison was killed. General Charles Gordon, the commander of the British-Egyptian forces, was beheaded during the attack.

In June 1885 Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, died. As a result the Mahdist movement quickly dissolved as infighting broke out among rival claimants to leadership. Hoping to capitalize on internal strife, the British returned to the Sudan in 1896 with Horatio Kitchener as commander of another Anglo-Egyptian army. In the final battle of the war on September 2, 1898 at Karari, 11,000 Mahdists were killed and 16,000 were wounded.

Ahmad’s successor called the Khalifa fled after his forces were overrun. In November of 1899 he was found and killed, officially ending the Mahdist state. Exacting vengeance for the death of Charles Gordon a decade earlier, Kitchener exhumed Ahmad’s body and pulled out his fingernails.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African History (New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004); C. Brown, “The Sudanese Mahdiya,” in Protest and Power in Black Africa, edited by R. I. Rotberg and A. Mazrui (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970); R. O. Collins, The Southern Sudan, 1883-98: A Struggle for Control (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962).