https://arab.news/8amc7

LONDON: Some Britons are feared to have been left behind in Sudan after reports that the country’s armed forces had stopped a number of people from reaching the final British evacuation flights out of the country on Saturday.

The final Royal Air Force flight left the Wadi Saeedna airfield north of Khartoum late on Saturday, four hours behind schedule, taking the number of Britons and their relatives evacuated since Tuesday to 1,888.

The UK pledged to maintain support for Britons trapped in the war-torn country but said conditions had grown too dangerous to continue evacuation flights.

The Conservative chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee told The Observer she had received information that elements of the Sudanese Armed Forces had blocked British citizens as they tried to arrive at an airbase north of Khartoum.

“I’ve had some messages saying the Sudanese armed forces have been stopping people from crossing through Khartoum to get to the airstrip,” Alicia Kearns MP said.

“I think we need to look into that and see if that’s got any truth to it. If so, you’ve got British nationals who are stuck and being stopped from getting to the evacuation point,” she added.

Hundreds of people were told to make the risky journey to an evacuation center at the Wadi Saeedna airbase, about 14 miles north of Khartoum, while Sudan’s armed forces continued to attack Rapid Support Forces positions.

The UK government denies it has abandoned anyone in Sudan, after accusations of repeating the mistakes of its chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Heavy fighting continued to rock Khartoum on Sunday and Sudan’s former Premier Abdalla Hamdok warned of the “nightmare” risk of a descent into full-scale civil war.

WASHINGTON: UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres is sending an envoy to the Sudan region amid the “unprecedented” situation there, as deadly hostilities enter a third week, his spokesman said Sunday.

The announcement came as the army and heavily armed paramilitaries in Khartoum continued fighting, even as a widely breached cease-fire was extended for 72 hours.

UN emergency relief coordinator Martin Griffiths, who will serve as the envoy, said in a separate statement Sunday that Sudan’s “humanitarian situation is reaching breaking point.”

“I am on my way to the region to explore how we can bring immediate relief to the millions of people whose lives have turned upside down overnight,” he said.

However, massive looting of humanitarian offices and warehouses had “depleted most of our supplies. We are exploring urgent ways to bring in and distribute additional supplies,” he said.

The “obvious solution,” he added, would be to “stop the fighting.”

More than 500 people have been killed and tens of thousands of people forced to leave their homes for safer locations within the country or abroad since battles erupted on April 15.

“In light of the rapidly deteriorating humanitarian crisis in Sudan,” spokesman Stephane Dujarric said in a statement announcing Griffiths’ deployment, the envoy would travel “to the region immediately.”

“The scale and speed of what is unfolding is unprecedented in Sudan,” his statement said. “We are extremely concerned.”

Griffiths said that families were struggling to access water, food, fuel and other commodities, with some unable to relocate due to the cost of transportation out of the worst-hit areas.

Urgent health care, he said “is severely constrained, raising the risk of preventable death.”

Five containers of intravenous fluids and other emergency supplies were docked in Port Sudan awaiting clearance by authorities, he added.

ROME: Although Sudan has been in the throes of political turmoil since authoritarian leader Omar Al-Bashir was toppled in 2019, the sudden explosion of violence that began on April 15 appeared to catch the world by surprise.

Explosions and gunfire in the capital Khartoum and elsewhere across the country, in defiance of repeated attempts to broker a cease-fire, have forced nations to hastily extract embassy staff and citizens who were at risk of being caught in the crossfire.

However, for many Sudanese citizens now forced to decide whether to remain in their homes, deprived of basic utilities, with food and medicine dwindling, or risk their lives by taking one of the increasingly lawless roads out of the country, signs of the coming crisis were all too clear.

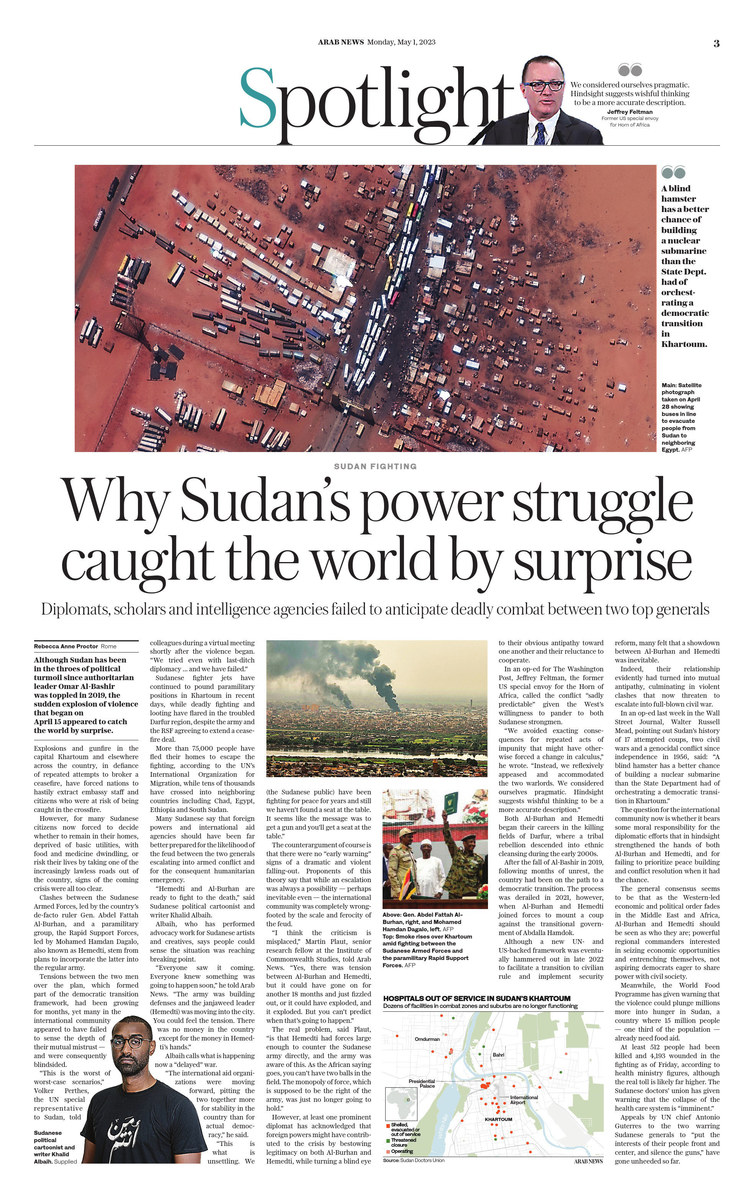

Clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces, led by the country’s de-facto ruler General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, and a paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces, led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, stem from plans to incorporate the latter into the regular army.

Tensions between the two men over the plan, which formed part of the democratic transition framework, had been growing for months, yet many in the international community appeared to have failed to sense the depth of their mutual mistrust — and were consequently blindsided.

“This is the worst of worst-case scenarios,” Volker Perthes, the UN special representative to Sudan, told colleagues during a virtual meeting shortly after the violence began. “We tried even with last-ditch diplomacy … and we have failed.”

Sudanese fighter jets have continued to pound paramilitary positions in Khartoum in recent days, while deadly fighting and looting have flared in the troubled Darfur region, despite the army and the RSF agreeing to extend a cease-fire deal.

More than 75,000 people have fled their homes to escape the fighting, according to the UN’s International Organization for Migration, while tens of thousands have crossed into neighboring countries including Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia and South Sudan.

Many Sudanese say that foreign powers and international aid agencies should have been far better prepared for the likelihood of the feud between the two generals escalating into armed conflict and for the consequent humanitarian emergency.

“Hemedti and Al-Burhan are ready to fight to the death,” said Sudanese political cartoonist and writer Khalid Albaih.

Albaih, who has performed advocacy work for artists and creatives in Sudan, believes Sudanese could sense in recent months that the situation was reaching a breaking point.

“Everyone saw it coming. Everyone knew something was going to happen soon,” he told Arab News. “The army was building defenses and the janjaweed leader (Hemedti) was moving into the city. You could feel the tension. There was no money in the country except for the money in Hemedti’s hands.”

Albaih calls what is happening now a “delayed war.”

“The international aid organizations were moving forward, pitting the two together more for stability in the country than for actual democracy,” he said.

“This is what is unsettling. We (the Sudanese public) have been fighting for peace for years and still we haven’t found a seat at the table. It seems like the message was to get a gun and you’ll get a seat at the table.”

The counterargument of course is that there were no “early warning” signs of a dramatic and violent falling-out. Proponents of this theory say that while an escalation was always a possibility — perhaps inevitable even — the international community was completely wrong-footed by the scale and ferocity of the feud.

“I think the criticism is misplaced,” Martin Plaut, senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, told Arab News. “Yes, there was tension between Al-Burhan and Hemedti, but it could have gone on for another 18 months and just fizzled out, or it could have exploded, and it exploded. But you can’t predict when that’s going to happen.”

The real problem, said Plaut, “is that Hemedti had forces large enough to counter the Sudanese army directly, and the army was aware of this. As the African saying goes, you can’t have two balls in the field. The monopoly of force, which is supposed to be the right of the army, was just no longer going to hold.”

However, at least one prominent diplomat has acknowledged that foreign powers might have contributed to the crisis by bestowing legitimacy on both Al-Burhan and Hemedti, while turning a blind eye to their obvious antipathy toward one another and their reluctance to cooperate.

In an op-ed for The Washington Post, Jeffrey Feltman, the former US special envoy for the Horn of Africa, called the conflict “sadly predictable” given the West’s willingness to pander to both Sudanese strongmen.

“We avoided exacting consequences for repeated acts of impunity that might have otherwise forced a change in calculus,” he wrote. “Instead, we reflexively appeased and accommodated the two warlords. We considered ourselves pragmatic. Hindsight suggests wishful thinking to be a more accurate description.”

Both Al-Burhan and Hemedti began their careers in the killing fields of Darfur, where a tribal rebellion descended into ethnic cleansing during the early 2000s.

After the fall of Al-Bashir in 2019, following months of unrest, the country had been on the path to a democratic transition. The process was derailed in 2021, however, when Al-Burhan and Hemedti joined forces to mount a coup against the transitional government of Abdalla Hamdok.

Although a new UN- and US-backed framework was eventually hammered out in late 2022 to facilitate a transition to civilian rule and implement security reform, many felt that a showdown between Al-Burhan and Hemedti was inevitable.

Indeed, their relationship evidently had turned into bitter animosity, culminating in violent clashes that now threaten to escalate into full-blown civil war.

In a scathing oped last week in the Wall Street Journal, the American columnist Walter Russell Mead, pointing out that Sudan has a history of 17 attempted coups, two civil wars and a genocidal conflict since independence in 1956, said: “A blind hamster has a better chance of building a nuclear submarine than the State Department had of orchestrating a democratic transition in Khartoum.”

The question for the international community now is whether it bears some moral responsibility for the diplomatic efforts that in hindsight strengthened the hands of both Al-Burhan and Hemedti, and for failing to prioritize peace building and conflict resolution when it had the chance.

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

The general consensus seems to be that as the Western-led economic and political order fades in the Middle East and Africa, actors such as Al-Burhan and Hemedti should be seen as who they are: powerful regional commanders interested in seizing economic opportunities and entrenching themselves, not aspiring democrats eager to share power with civil society.

Meanwhile, the World Food Programme has given warning that the violence could plunge millions more into hunger in Sudan, a country where 15 million people — one third of the population — already need aid to stave off famine.

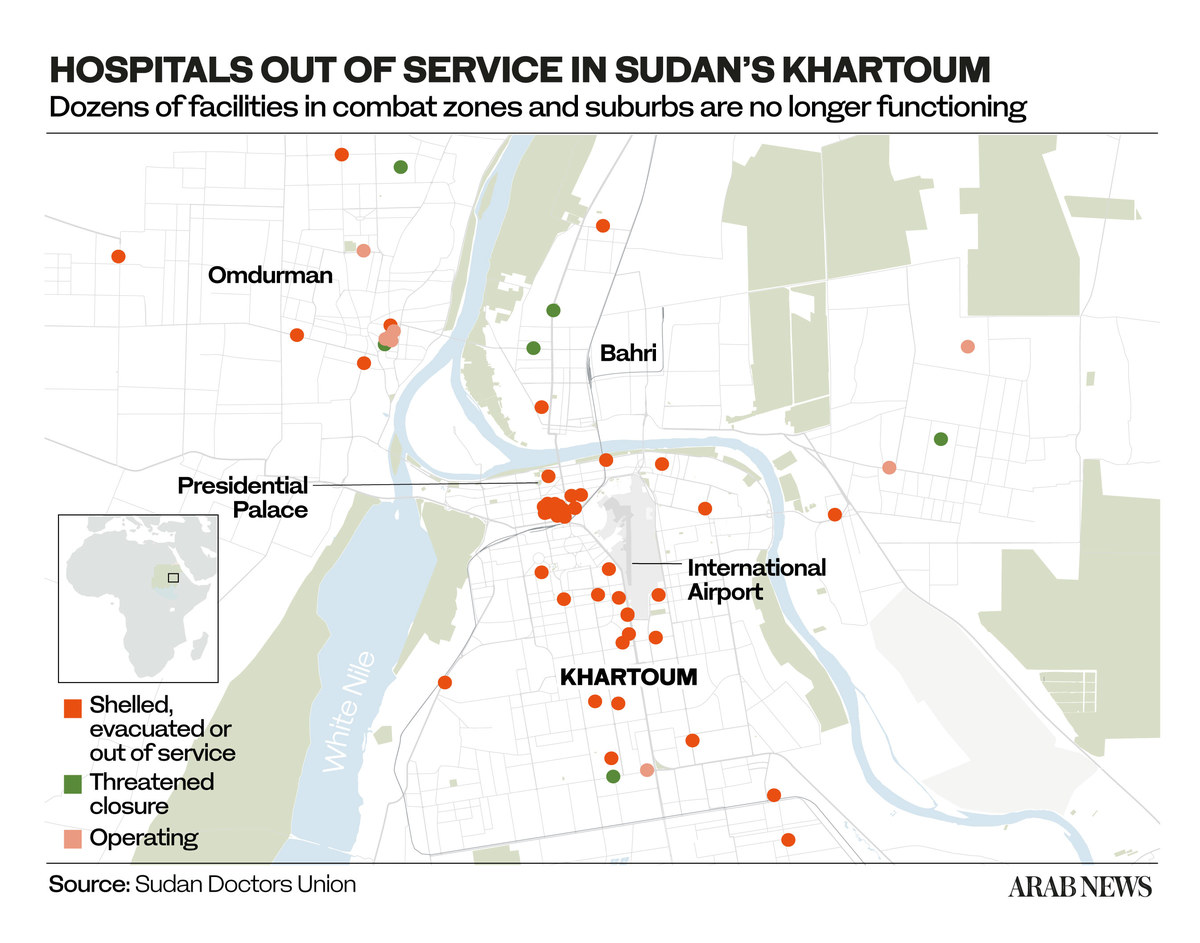

At least 528 people had been killed and 4,599 wounded in the fighting as of April 30, according to health ministry figures, although the real toll is likely far higher. The Sudanese doctors’ union has given warning that the collapse of the health care system is “imminent.”

Appeals by UN chief Antonio Guterres to the two warring Sudanese generals to “put the interests of their people front and center, and silence the guns,” have gone unheeded so far.

CAIRO: Sudan’s army and its rival paramilitary said Sunday they will extend a humanitarian cease-fire a further 72 hours. The decision follows international pressure to allow the safe passage of civilians and aid, but the shaky truce has not so far stopped the clashes.

In statements, both sides accused the other of violations. The agreement has deescalated the fighting in some areas but violence continues to push civilians to flee. Aid groups have also struggled to get badly needed supplies into the country.

The conflict erupted on April 15 between the nation’s army and its paramilitary force, and threatens to thrust Sudan into a raging civil war. The UN warned on Sunday that the humanitarian crisis in Sudan was at “a breaking point.”

“The scale and speed of what is unfolding in Sudan is unprecedented,” the UN’s humanitarian chief Martin Griffiths said in a statement.

He said water and food are becoming increasingly hard to find in the country’s cities, especially the capital, Khartoum, and that the lack of basic medical care means many could die of preventable causes. Griffiths said that “massive looting” of aid supplies has hindered efforts to help civilians.

Earlier Sunday, an aircraft carrying eight tons of emergency medical aid landed in Sudan to resupply hospitals devastated by the fighting, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross, which organized the shipment. It arrived as the civilian death toll from the countrywide violence topped 400 and aid groups warned that the humanitarian situation was becoming increasingly dire.

More than two-thirds of hospitals in areas with active fighting are out of service, a national doctors’ association has said, citing a shortage of medical supplies, health workers, water and electricity.

The air-lifted supplies, including anesthetics, dressings, sutures and other surgical material, are enough to treat more than 1,000 people wounded in the conflict, the ICRC said. The aircraft took off earlier in the day from Jordan and safely landed in the city of Port Sudan, it said.

“The hope is to get this material to some of the most critically busy hospitals in the capital” of Khartoum and other hot spots, said Patrick Youssef, ICRC’s regional director for Africa.

The Sudan Doctors’ Syndicate, which monitors casualties, said Sunday that over the past two weeks, 425 civilians were killed and 2,091 wounded. The Sudanese Health Ministry on Saturday put the overall death toll, including fighters, at 528, with 4,500 wounded.

Some of the deadliest battles have raged across Khartoum. The fighting pits the army chief, Gen. Abdel Fattah Burhan, against Gen. Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, the head of a paramilitary group known as the Rapid Support Forces.

The generals, both with powerful foreign backers, were allies in an October 2021 military coup that halted Sudan’s fitful transition to democracy, but they have since turned on each other.

Ordinary Sudanese have been caught in the crossfire. Tens of thousands have fled to neighboring countries, including Chad and Egypt, while others remain pinned down with dwindling supplies. Thousands of foreigners have been evacuated in airlifts and land convoys.

On Sunday, fighting continued in different parts of the capital where residents hiding in their homes reported hearing artillery fire. There have been lulls in fighting, but never a fully observed cease-fire, despite repeated attempts by international mediators.

Over the weekend, residents reported that shops were reopening and normalcy gradually returning in some areas of Khartoum as the scale of fighting dwindled after yet another shaky truce. But in other areas, terrified residents reported explosions thundering around them and fighters ransacking houses.

Youssef, the ICRC official, said the agency has been in contact with the top command of both sides to ensure that medical assistance could reach hospitals safely.

“With this news today, we are really hoping that this becomes part of a steady coordination mechanism to allow other flights to come in,” he said.

Youssef said more medical aid was ready to be flown into Khartoum pending necessary clearances and security guarantees.

Sudan’s health care system is near collapse with dozens of hospitals out of service. Multiple aid agencies have had to suspend operations and evacuated employees.

On Sunday, a second US-government organized convoy arrived in Port Sudan, said State Department Spokesperson Matthew Miller. He said the US is assisting American citizens and “others who are eligible” to leave for Saudi Arabia where US personnel are located. There were no details on how many people were in the convoy or specific assistance the US provided.

Most of the estimated 16,000 Americans believed to be in Sudan right now are dual US-Sudanese nationals. The Defense Department said in a statement on Saturday it was moving naval assets toward Sudan’s coast to support further evacuations.

MOSCOW: Saudi Arabia has evacuated dozens of Russian citizens from Sudan by warships, it was announced on Sunday.

This is according to Ruslan Usmanov, press attache of the Consulate General of the Russian Federation in Jeddah, in an interview with a correspondent of TASS, Russia’s news agency.

“Russians are not evacuating on their own, they are being taken out by Saudi Arabian warships. They took over the issue, they are taken out of the port of Sudan, then they are brought to the port of Jeddah to the naval base. We meet them there,” the diplomat said.

“At the moment, about 40 Russians have arrived,” he added. “Most of them have already left, some to Russia, some to other countries, depending on who has what destination.”

Russian citizens have been leaving for their homeland, Usmanov clarified, through transit countries including Egypt, the UAE and Qatar.

He said Saudi Arabia has been evacuating citizens from other nations including the US, and those from the EU.

The authorities of the country, he continued, provide the Russian consulate with information on the list of evacuees.

“The Saudi side, in principle, still pays them for two-day hotel accommodation with meals,” Usmanov said. “After that, the citizens of the Russian Federation leave for Russia. If necessary, we accompany them to the airport, solve some issues, but as a rule everything goes smoothly and clearly. There are no problems yet.”

Recently, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova confirmed in an interview with Arab News that Moscow is in contact with Riyadh about the evacuation of Russian citizens and diplomats from Sudan.