Hawker centres have undeniably become part of the Singaporean culture. Besides enjoying kopitiam dishes on the regular, there’s a universal sense of pride whenever we introduce hawker food to our foreign friends – boasting its affordability, accessibility and tastiness.

For something that’s so integrated into our daily lives regardless of what age we are, there’s still a number of unexplored facts we tend to gloss over. Read on to discover 10 surprising things you probably never knew about Singapore’s hawker food.

Image credit: Eatbook

We’re all familiar with yong tau foo – a typical Hakka dish where you kiap your desired toppings before handing them over to the hawker to cook. Fun fact: “yong” actually means “stuffed” in Hakka dialect. Over time, the term yong tau foo became a collective term for various stuffed and boiled food items, but it was originally meant to just refer to stuffed tofu.

Common ingredients in this healthier kopitiam choice include fish balls, tau kua, okra and an array of fish paste-filled items. But back in its birthplace of China, ingredients were originally filled with minced meat, and the use of fish paste only began when the Hakkas migrated over to Southeast Asia.

With the abundance of seafood here given our early beginnings as a fishing village, hawkers began incorporating fish paste to save money on pricier meat filling.

With so many variations of chicken rice in the SEA region, it’s hard to pinpoint the OG. Following its name, the version from Hainan, China was known as Wenchang chicken – a skinny breed of fowl that has minimal meat. In the original rendition, the dish was paired with rice cooked in a mixture of pork bone and chicken bone stock.

Image adapted from: Eatbook

In our local context, however, only chicken stock is used in the rice cooking process, and pork bone stock is rarely added.

Local hawkers have also opted to use younger and fleshier chicken, inspired by the Cantonese dish of pak cham kai or white cut chicken. The culinary technique involves plunging freshly boiled meat into ice water to make the skin silky and jelly-like. This – together with piquant additions of fresh minced chilli, garlic and ginger – has formed our signature version of the age-old dish.

Image credit: @celiachangchi

A plate of mamak stall mee goreng hits different any time of the day, but did you know that “Indian mee goreng” is not actually a thing in India? Kind of like how Chinese restaurants in Western countries have dishes called “Singapore noodles“, when that’s not even a thing in Singapore.

“Mee” means noodles in Hokkien, and “goreng” means fried in Malay. This fried noodle dish was initially sold by early Indian-Muslim hawkers who whipped up their dishes on tricycle-mounted woks, and it’s now become a mainstay at 24-hour food haunts around the island.

Comprising ingredients from an array of cuisines, you’ll find Chinese yellow noodles and dark soy sauce, Western tomato sauce and tomatoes, and Indian chilli and curry flavours in this hearty dish.

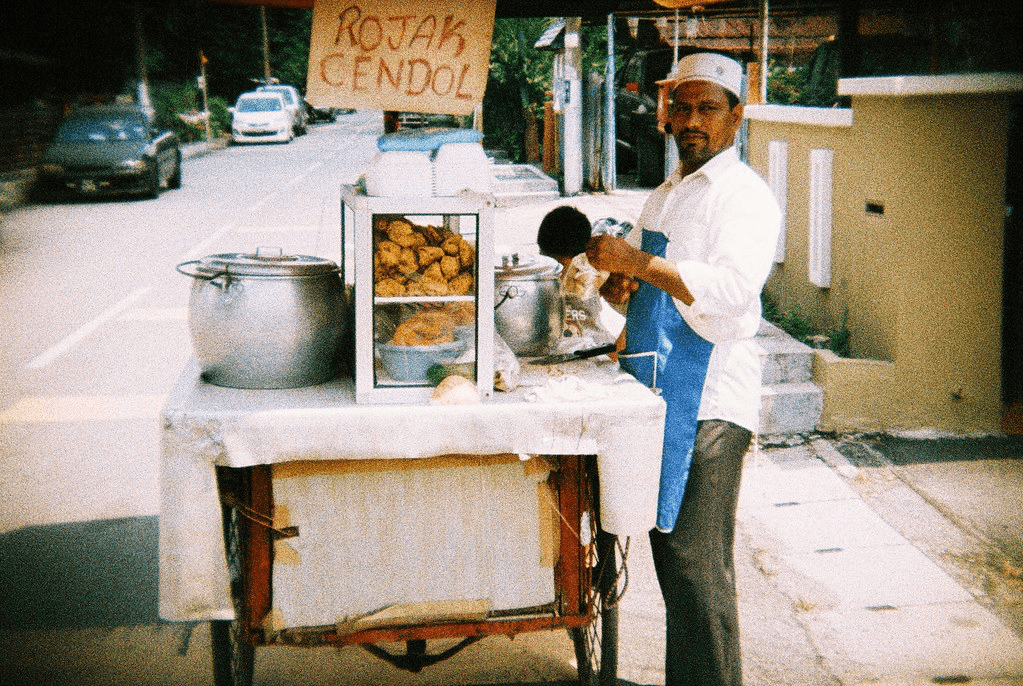

Up until the 1980s, rojak was sold in Singapore via bicycle or pushcart peddling, which was illegal without a licence.

Image credit: Flickr

These rojak peddlers could be easily identified by the glass panels that showcased the quintessential ingredients, providing a variety of colours and textures. They would then mix the ingredients with the iconic thick sweet sauce on the spot, before handing it over to their hungry patrons.

Rojak in Singapore comes in slightly differing forms, incorporating ingredients from around the region and influenced by various ethnic groups. For example, Chinese rojak doesn’t contain eggs – but has Chinese staples like tau pok, tau kwa and you tiao, whereas Indian rojak doesn’t contain bean sprouts.

It makes sense that the dish reflects the cultural diversity of Singapore, which is often described as “rojak” due to the harmonious blend.

Image adapted from: Eatbook

Presently, hawkers have found a permanent spot in hawker centres instead of the streets. We can now head over to our favourite rojak stalls without worrying that it’s cycled off to the other end of the country.

Curry puffs will always be one of the go-to grab-and-go snacks for busy Singaporeans. It’s affordable, easy to get and substantial enough to keep your stomach from growling till your next meal.

British cornish pasty (left) and Portuguese empanada (right)

Image credit: Great British Chefs, Daisy’s Kitchen

Other than British cornish pasty, the Portuguese empanada and the Indian samosa, the Chinese curry puff can be also traced to the Malay fan favourite: epok-epok. The Chinese version uses a filling comprising curry chicken, potatoes and the treasure find everyone looks forward to: the bits of hard-boiled eggs.

Image credit: Eatbook

The creation of our famed chilli crab was due to a fortuitous experiment that happened in 1956. Back then, Madam Cher Yam Tian – co-founder of Palm Beach Seafood Restaurant – had been frying up the restaurant’s usual stir-fried crab dish when her husband toyed with the idea of trying something different.

This led to her frying up the crabs in tomato sauce in addition to the concoction of Malay spices and soybean paste. After a taste test, Mr Lim found the taste to be pleasant but a tad too sweet, and suggested adding some chilli sauce. The rest, as they say, is history.

I think I speak for all of us when I say: thank heavens for this mistake, or we wouldn’t have this delectable dish to wow our foreign friends with, or mop up with our fluffy mantou buns.

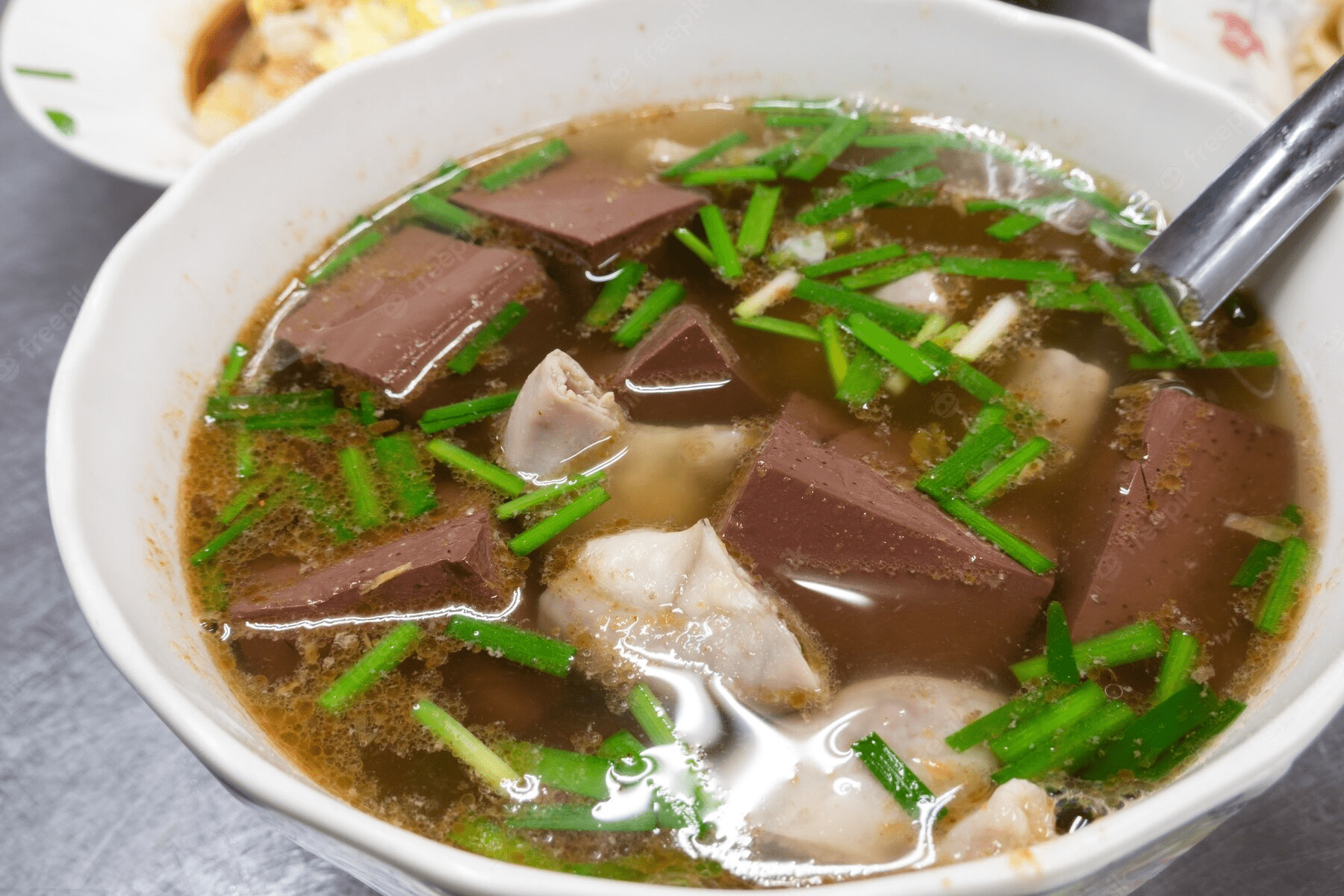

Image credit: Freepik

When I asked my mum about pig blood curds, she nonchalantly replied: “Yeah, quite yummy. Pretty soft and nice with soup.”

I then delved deep into research and learnt that pig blood curds – alongside pig intestines and pork meat – used to be added to pig organ soups to give the broth a sweet umami taste. It was common practice and the curds usually came in the form of cubes.

However, due to the Nipah virus outbreak in 1999, pig’s blood was banned in Singapore for its high food safety risk. It has since been replaced by blood-free tofu chunks.

Singaporeans have a knack for remaking culinary creations with a local twist, imparting flavours from our Little Red Dot’s medley of ethnicities and also making full use of the local produce available.

Take Hokkien mee, for example. The dish hailing from Fujian, China uses flat noodles. Meanwhile, round noodles are used in the Singaporean version, fried in a paler gravy and finished with the addition of a juicy lime and dollop of sambal belacan – an aromatic chilli paste with fermented shrimp. The result is a union of Chinese and Malay ingredients, and now we can’t imagine slurping up Hokkien mee without sambal.

Image adapted from: Eatbook

In terms of utilising the ingredients abundant on home soil, the Singapore version of popiah – a dish from Fujian and Chaoshan in China – uses the locally available bang kuang or jicama, a.k.a. Mexican turnip. This is in place of the original bamboo shoots, and the rare grass kelp.

While jam on toast is a quintessential breakfast treat, kaya is our local take on a hearty spread to enjoy with bread. A spin-off of fruit jam found in English breakfasts, kaya is made up of coconut milk, eggs, sugar, and the fragrant ingredient beloved by young and old: pandan leaves.

Image credit: Eatbook

While we may shriek and demand a refund when we find critters in our food, this would not be the common reaction back in the 50s.

When prepping and cooking laksa, earthworms were apparently added to the dish to enhance the broth’s saltiness, and maggots were included as they were thought to “eat away” all the bacteria. So the next time you find a creepy crawly at the bottom of your bowl, maybe consider mixing it in with whatever you’re eating – for health and taste benefits. Just kidding.

We generally classify our bak kut teh soups as “white” or “black” – white being the peppery one and black being the herbally version. While this technically isn’t wrong, the original form of boiled pork ribs soup from Fujian has actually been adapted by the Teochew, Cantonese and Hokkien folks in Singapore to form three different variations.

Image credit: Eatbook

The one which Singaporeans are most familiar with would probably be the Teochew version. This variation stands out among the three with its light coloured soup base that features only garlic, soy sauce and pepper. It is then simmered and skimmed, unlike the Hokkien version that is boiled.

Hokkien version (left) and Cantonese version (right)

Image adapted from: Eatbook, More Than Veggies

The Hokkien version has a strong aroma due to the addition of rock sugar and a myriad of herbs. Large amounts of dark soy sauce are also added – giving it its signature dark brown, cloudy appearance and thicker consistency.

On the other hand, the Cantonese version leans towards a less salty, more herbal flavour, replacing the dark soy sauce with copious amounts of medicinal herbs. Alongside this is the addition of braised shiitake mushrooms, Chinese cabbage and beancurd.

Food is never just food in Singapore. There’s a story and reason for how each dish has progressed through the years, and how we’ve come to make them our own. Now you’ll have fun facts to spew when you’re out with your friends – like how yong tau foo went from meat- to fish-filled and when blocks of blood were scrapped from pig organ soup.

Beyond the local food scene, there’s also tons of discoveries to be made about our Little Red Dot and our unique culture. Find them all conveniently consolidated at the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre (SCCC), which has eye-opening and informative exhibitions for us to visit and expand our knowledge of Singapore.

For the curious foodies, the Secret Ingredients Travelling Exhibition explores our local fare, bringing participants on a hunt to solve clues and decrypt key ingredients for dishes like the aforementioned yong tau foo, bak kut teh and laksa. Channel your inner Sherlock Holmes as you investigate the mysteries at each station. From now till 31st March 2022, you can check out the Secret Ingredients exhibition at Waterway Point, B2 The Cove.

Image credit: SCCC

Available till 31st March 2022 at SCCC’s Ho Bee Concourse, the One Of Us, All Of Us Exhibition sheds light on the heritage of our various Chinese dialect groups. Through storytelling and visuals, the exhibition features local stories you wouldn’t otherwise get to hear of – including the tale of Mr Ngaim Tong Boon – the man who created the Singapore Sling, the only one drink in the world that bears our country’s name.

Image credit: SCCC

We’re all familiar with the adorable Ang Ku Kueh Girl merch and through expressive Telegram stickers. From now till 30th June 2022, the Life Is Sweet: Ang Ku Kueh Girl exhibition will showcase the endearing character as she shares relatable happenings told through a cutesy lens. Find these cartoons, illustrated by the creator herself, Wang Shijia, at SCCC’s Level 9 and 10 foyers.

Alongside these exhibitions is SCCC’s Ways of Being video series. The 10-part series uncovers the values that Singaporeans hold close to heart – such as integrity and filial piety – and how these might have evolved over time. Starting 24th February 2022, an episode will be released online monthly, so you have plenty of time for deep talks with your pals on each topic.

SCCC is also holding a giveaway on their social media, where the winner will walk away with dining vouchers worth $100. To participate, snap a photo of your favourite SCCC showcase in the most innovative way and share what it represents or the memories that come with it. Find out the full details by checking out the SCCC giveaway announcement.

If you enjoyed reading about our Lion City’s hawker food facts, give these SCCC exhibitions a visit and bring along your friends and family. Who knows, you may walk away with new tidbits of info to impress others with.

Address: 1 Straits Boulevard, Singapore 018906

Nearest MRT station: Tanjong Pagar

SCCC website

Events are held at different timings, do refer to the SCCC events page for their respective opening hours.

This post was brought to you by SCCC.

Cover image adapted from: Eatbook

Singapore Office

219 Kallang Bahru, #04-00 Chutex Building, Singapore 339348

Phone: 6514 0510

The opinions expressed by our users do not reflect the official position of TheSmartLocal.com or its staff.

All rights reserved 2012 — 2022 TheSmartLocal.com