Banks risk widening trade finance gap as they push for green label

Insight Weekly: Stocks endure more pain; bank branch M&A slows; debt ratios fall

Street Talk | Episode 100 – KBW CEO offers optimism for bears fearful of bank liquidity, credit

Insight Weekly: Unease roils markets; US likely to slip into recession; firms’ cash ratios fall

Insight Weekly: Dealmaking slumps; rate hikes hammer gold; transaction banking revenues jump

As banks expand their sustainable trade finance offerings to meet growing corporate demand, they face a challenge to ensure that stricter environmental, social and governance criteria do not worsen the trade finance gap by cutting off access to financing for companies that need it most.

“We need an honest debate about this. Yes, it could potentially widen the trade finance gap,” Rebecca Harding, CEO of trade data provider Coriolis Technologies, told S&P Global Market Intelligence on the sidelines of the International Trade and Forfaiting Association‘s annual conference on Sept. 8. “But, equally, if trade finance is doing its job properly, what it could do is create a transition.”

HSBC Holdings PLC, one of the world’s largest trade finance banks, said it has seen an “unprecedented surge in demand” for sustainable trade finance products, particularly in the wake of COVID-19.

More banks are rolling out green or sustainability-linked equivalents of trade finance to meet corporate demand and support their own sustainability commitments. Trade finance comprises financial instruments that support a company’s imports and exports.

Last year, Standard Chartered PLC launched a proposition focusing on sustainable supply chain finance, invoice financing, receivables services and guarantees and letters of credit. Citigroup Inc. followed this year with the introduction of a new sustainable trade and working capital loans solutions. Such products typically support green trade activities or link financing to sustainability performance or ESG scores.

Mind the gap

As trade finance banks embrace ESG, some industry players worry that implementing stricter sustainability criteria into funding conditions will make it harder for companies to access trade finance.

“My concern is, if we are going to deny financing based on someone’s ESG score, are we going to widen the trade finance gap?” said Merlin Dowse, global product manager for trade and working capital at JPMorgan Chase & Co., speaking at a Global Trade Review event on June 15.

The trade finance gap, which reflects the disparity between demand and supply for trade finance, is already at an all-time high, having reached $1.7 trillion in 2020, according to the latest estimate by the Asian Development Bank. Small and medium-sized enterprises are hardest hit, accounting for 40% of rejected trade finance requests.

If sustainable trade finance structures are static and punitive toward companies that do not meet certain ESG criteria, it could worsen some entities’ access to funding, said Harding.

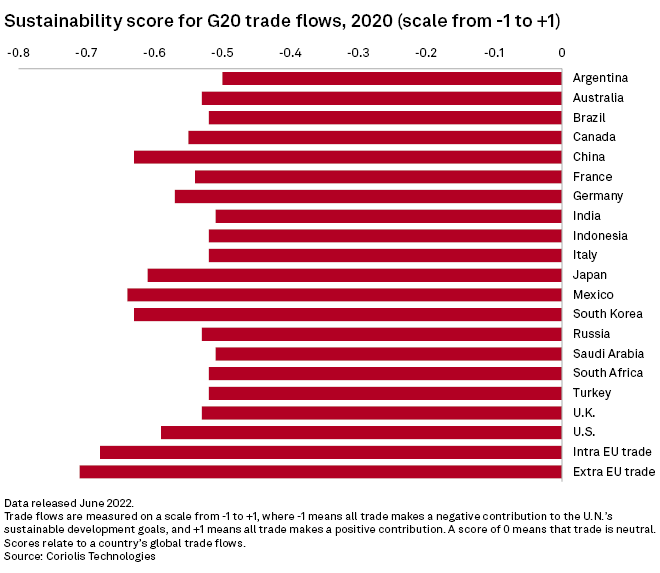

Research by Coriolis Technologies mapped 2020 global trade flows against the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals, finding that nearly 80% of the value of world trade was unsustainable according to those measures.

Making trade finance inclusive

Across the industry, banks and other actors are collaborating to drive further growth in sustainable trade finance. The International Trade and Forfaiting Association, or ITFA, last year formed an ESG committee focused on education, standardization of frameworks and advocacy. The International Chamber of Commerce is working with more than 200 banks and corporates to define standards for sustainable trade and trade finance and is due to release its findings later this year. Banks including NatWest Group PLC and Lloyds Banking Group PLC are cooperating with Coriolis Technologies to drive the adoption of standardized ESG scoring criteria.

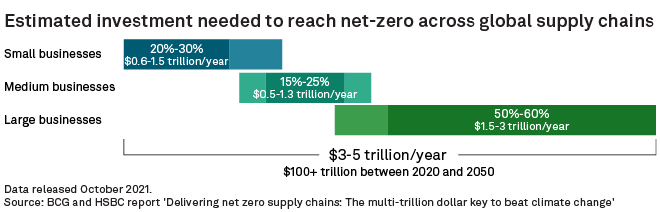

Trade finance will be a “massive lever” to reach the world’s climate goals, said Surath Sengupta, global head of portfolio management and sustainability at HSBC. Global supply chains will need some $100 trillion of investment by 2050 if they are to achieve net-zero emissions, according to research by HSBC and Boston Consulting Group released last year.

Unlike traditional green bonds and loans, which focus on a company’s own transition, sustainable trade finance can help firms drive change in their downstream and upstream supply chains, Sengupta said in an interview.

A supply chain finance program, for example, is typically set up by a large corporate buyer with its bank to offer cheaper financing to suppliers that meet certain sustainability criteria.

“What companies have realized is that if they transition, that is just not enough,” Sengupta said. “Up to 80% of companies’ carbon footprint is in their supply chains. So unless they help their supply chains transition, how are they going to achieve the objectives around sustainability that their consumers and investors are demanding?”

Financial institutions now face a challenge to design sustainable trade finance structures that are inclusive and incentivize change — something bankers believe can be done.

“If trade finance is done the right way, it is done to help SMEs come into the financing spectrum rather than leave it,” said Sengupta. Banks should look to create “more innovative new financing models” to support changing business models and supply chains, rather than only converting existing trade finance products into sustainable versions, he said. Lenders should also embrace the improved data and transparency of value chains to finance more parties than they could previously.

Sengupta expects the growth of sustainable trade finance will help the industry attract more institutional money as investor demand for ESG assets grows.

Importantly, sustainable supply chain finance programs should not be static, but rather help suppliers migrate into better sustainability categories through the right incentives, said Anil Walia, Deutsche Bank AG’s director of supply chain finance payables in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, speaking at ITFA’s annual conference in Porto on Sept. 7. Deutsche Bank aims to reach €1 billion in sustainable supply chain finance programs by the end of 2022, he said.

“It needs to be dynamic. The program should be able to, over a period of time, improve the sustainability in the ecosystem,” Walia said. If that does not happen, the bank will seek to agree with the corporate customer to change the funding conditions of a program, he said.

Emerging market sustainability

How trade finance providers define sustainable trade will also significantly impact which companies can and cannot access financing with an ESG label. If more companies are to benefit from sustainable trade finance, the industry needs to develop appropriate metrics to measure sustainability of trade outside of developed economies, said George Wilson, head of institutional trade finance at Investec, an international bank and wealth manager that specializes in trade finance in Africa.

Emerging taxonomies that define sustainable finance tend to focus on developed market issues such as the environment and carbon neutrality, and as such do not cater well for African trade finance, Wilson told S&P Global Market Intelligence. Trade finance in Africa is a key tool to deliver at least 12 nonenvironmental U.N. sustainable development goals, such as eradicating poverty and hunger, yet most African traders do not qualify for ESG-earmarked funding, he said.

“Additional ESG requirements have added a further challenge for African traders,” Wilson said. “As it’s currently panning out, in all likelihood, it will make the trade finance gap worse.”