In 2008, the Brown family watched on helplessly as destructive bushfires ripped through the Victorian countryside. For them, it was a wakeup call.

It was the third time in several years flames had come close to torching vineyards that five generations of their family had poured over a century of love and work into.

Warming days, declining rainfall and subsequent drought had snuck up on them, but this was a glaring warning sign they couldn’t ignore.

Climate change had become the family businesses’ “biggest threat”, Caroline Brown says.

It’s not a problem unique to the Browns – the family behind one of the oldest wine brands in Australia. The country is the world’s fifth-largest wine exporter and is home to a diverse array of wine regions most other countries could only dream of.

And while climate change is threatening winemakers worldwide, Australia’s industry is on the front lines.

A warming and drying trend

Ashley Ratcliff’s vineyards are already in one of the hottest and driest wine regions on the planet.

There was one year, he recalls, when their vineyards in South Australia’s Riverland region got only 90mm of rain – 10 times less than the annual average for the famous French wine region of Bordeaux.

“It was hot, everything was dirty and dusty,” he says. “And then on the other extreme, you get the really wet years where you never think it’s going to dry out.”

And it will only get worse.

In the next 20 years, the Riverland will be about 1.3 degrees hotter and rainfall will drop, according to modelling by Australian researchers.

With that will also come more extreme weather events, which are already a near constant in Australia.

The country is still recovering from years of record-breaking floods, but with an El Nino summer likely to bring dry and hot conditions to much of Australia, panic is growing ahead of the coming fire season.

What does that mean for wine?

While grapevines are described as “one of the most valuable weeds in the world”, capable of growing almost anywhere, the fruit itself is vulnerable to its environment.

And climate change is already messing with flavour and quality. Heat affects the speed at which the grapes ripen and with it, their sugar and acidity levels.

Already the growing season has shifted forward – by weeks in some places – which also impacts logistics and infrastructure.

Then there’s the impact of weather events driven by climate change, which at their worst can wipe out an entire season’s crop.

All of this means growing certain types of wine grapes in Australia – those suited to cooler climates like Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir – will only get harder.

Adaptation is key

The Ratcliffs strategically decided to plant “alternative” varieties more suited to warmer climes when they purchased their vineyards in 2003.

They deemed the risk posed by climate change as greater than that of selling lesser-known grapes. Two decades on, anyone not contemplating doing the same is kidding themselves, Mr Ratcliff says.

“There are all those fervent doomsday people. [But] I think there is an opportunity to rebrand and make the industry really exciting – to use climate change as a positive rather than a negative.”

The average consumer won’t notice a big difference between the wines they love and the up-and-coming alternative varieties that Ricca Terra sells – like Montepulciano, Fiano and Nero D’Avola. The grapes are hardier and often more planet-friendly too, requiring less water.

The Brown family too is growing alternative varieties, including some they created with Australia’s science agency. But they have also looked south to keep current favourites alive.

With climate change in mind, they began snapping up vineyards in cooler locations like Tasmania – a growing trend across the industry.

“We realised that having all of our vineyards in one location in Victoria meant we had all our eggs in one basket,” Ms Brown says.

But Tahbilk Winery’s Hayley Purbrick is one grower who is staying put, despite “confronting” climate modelling.

“We have a philosophy that our responsibility is to create a climate where grapes can grow,” she says. “There’s so much you can do at a local level and sometimes when we think [about climate change on a global scale] we get a bit too wrapped up in the impossibility of what we can’t do.”

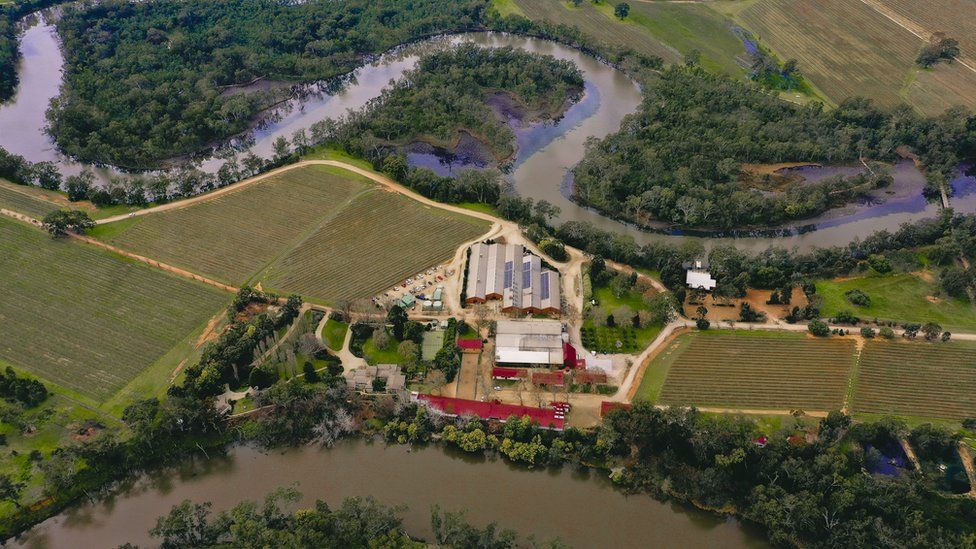

Her family’s vineyards in the Goulburn Valley incorporate as much shade and as many “natural coolants” as possible. They’re planted on the edge of wetlands and are surrounded by 160 hectares of trees.

They’ve also slashed their carbon emissions to net zero, through things like solar power, using heat reflective paint to limit the need for air conditioning, and reducing waste.

It’s working so far: “We’re lucky in the sense that we’re three degrees cooler than places even three kilometres away.”

But researcher Tom Remenyi says adaptation and mitigation can only take growers so far.

On the current trajectory, the whole of Australia is going to get warmer and dryer – and while a couple of degrees might not sound like a lot, it could be catastrophic, he says.

“A three-degree shift of the average increases the frequency of extremely hot days by about tenfold, if not more. If the whole globe warms more than three degrees, it’s highly likely that we will not be worried about growing wine.”

Optimism prevails

And that’s exactly what is weighing on growers like Caroline Brown. For her, the family business is inextricably entwined with the family history.

She spent her childhood getting into mischief with her cousins among the vineyards at Milawa. Now they all work in the business.

She desperately wants the same for the next generations.

“We’re very passionate about family,” she says. “Our great-grandfather started the business… we’d love one day for our great-grandchildren to be in the lucky positions we’re in.”

But she is well aware that climate change threatens that.

“If we don’t look after where we’re growing grapes then we’re not going to have any way to plant them in the future. So it is scary,” she says.

But there will be very few – if any – of the country’s favourite varieties it won’t be able to grow somewhere, she argues.

“You’ll always be able to grow Cabernet in Australia, but it just might not taste as good in the years to come.”

By Tiffanie Turnbull

BBC News, Sydney

source : https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-62489056