Context Assessment

3 March 2023

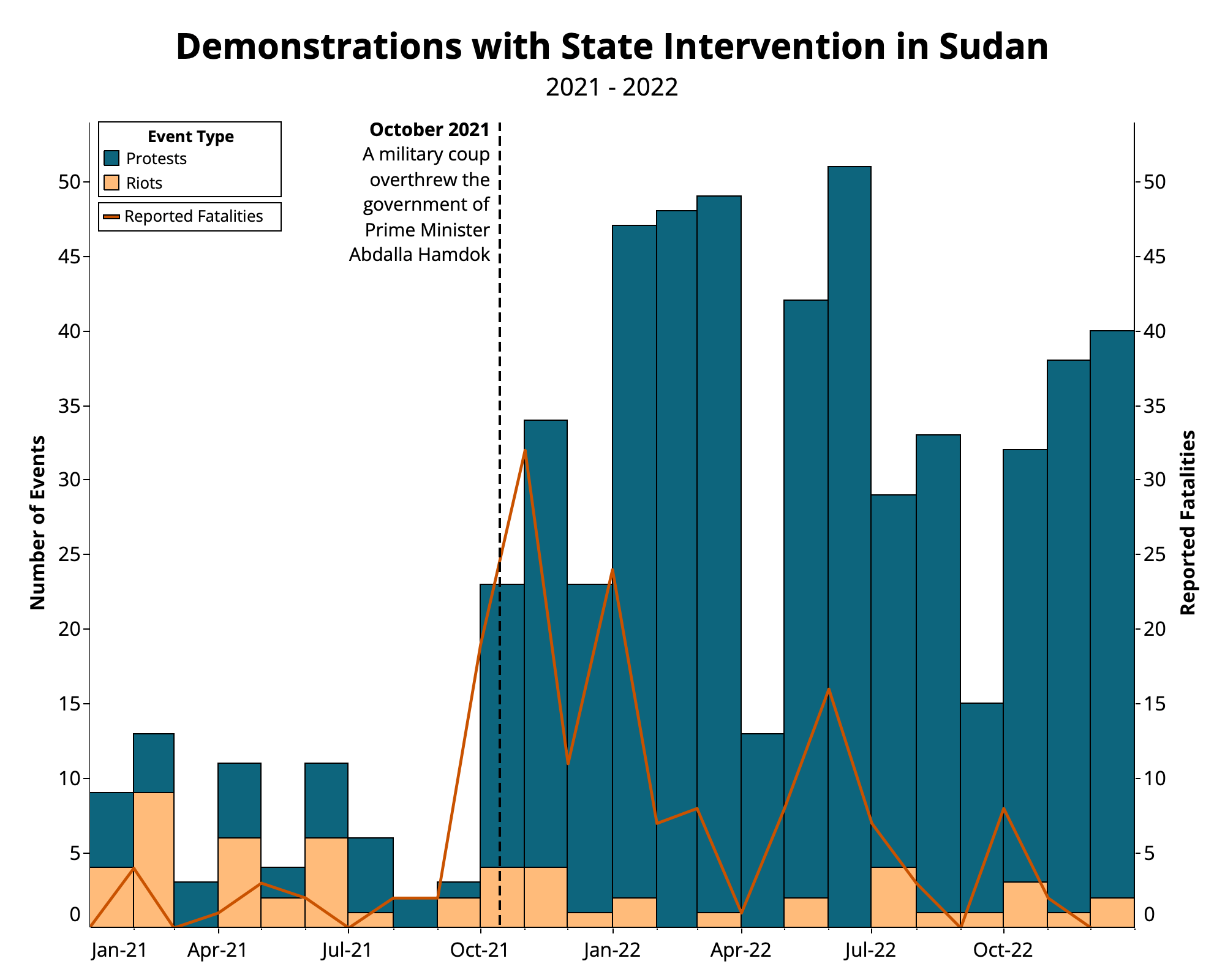

Over the past year, Sudan has been grappling with heightened insecurity and a rise in demonstration activity. Demonstration events more than doubled in 2022 compared with the number recorded in 2021, reflecting ongoing opposition to the military regime and support for a civilian government. In addition to the popular unrest, armed conflict involving state and non-state armed groups across the country has increased. Over half of the political violence events reportedly involved identity militias. Ongoing turmoil in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, has contributed to the escalation of the conflict, after a military coup d’état in October 2021 put the country on an uncertain path. Against this backdrop, the December 2022 signing of a political framework agreement is hoped to end the political stalemate and move Sudan toward a civilian government.

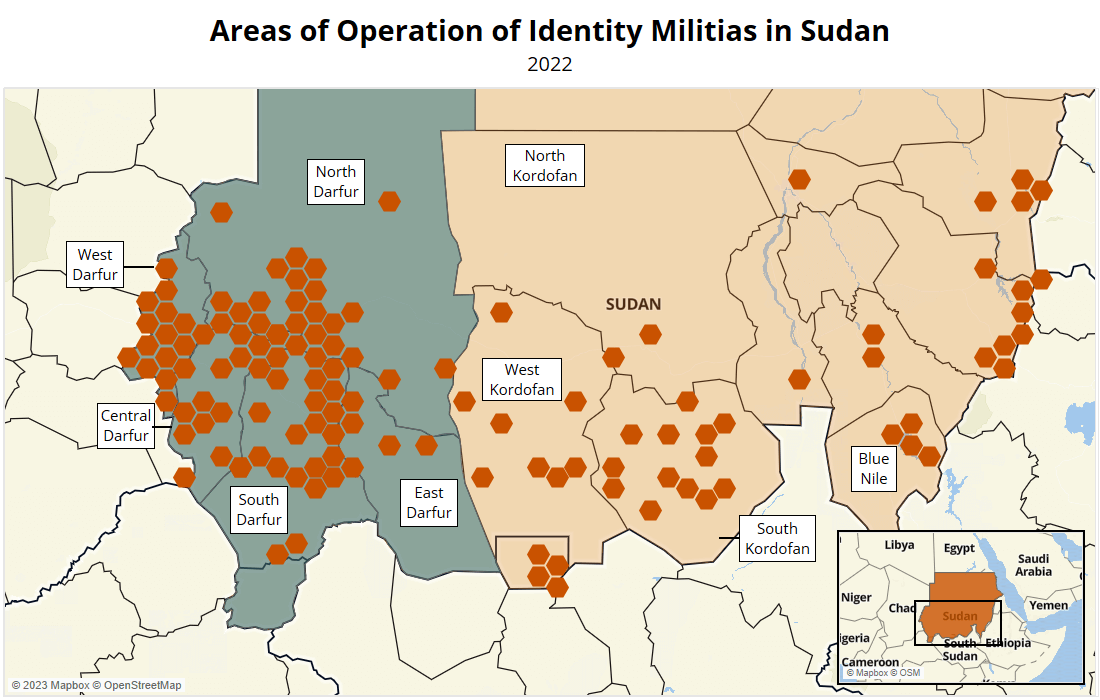

Last year was the deadliest year in Sudan since 2016, with identity militia activity resulting in over 86% of the reported fatalities. Darfur region especially bore the brunt of this violence (see map below). In West Darfur alone, political violence resulted in almost 500 reported fatalities in 2022, as Arab-identifying Rizeigat militias carried out retaliatory attacks against other ethnic groups.

The main drivers of conflict in the region include ongoing competition between communities affiliated with General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemeti – who now shares executive power in Khartoum after commanding the original Janjaweed and creating the notorious Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – and those affiliated with Darfuri opposition to the national government and its affiliates. At the community level, resource and land pressures erode cooperation between groups and lead to an increase in violence related to land authority and access.1Abdi Latif Dahir, ‘‘They Keep Killing Us’: Violence Rages in Sudan’s Darfur Two Decades On,’ New York Times, 19 March 2022 The Arab tribes in the area are mostly pastoralists whereas many of the farmers that settled in the region are from other minority ethnic groups, such as the Gimir and Masalit tribes.2Johan Brosché, ‘Conflict Over the Commons: Government Bias and Communal Conflict in Darfur and Eastern Sudan,’ Ethnopolitics, 19 January 2022

In August 2020, the Sudanese transitional government signed the Juba Agreement for Peace in Sudan with key rebel groups, which provided for transitional security arrangements in Darfur. These included a permanent ceasefire, the reintegration of rebel forces into national security forces, disarmament, and military and security reforms.3Denis Dumo, ‘Sudan signs key peace deal with key rebel groups, some hold out,’ Reuters, 31 August 2020; International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, ‘The Juba Agreement for Peace in Sudan: Summary and Analysis,’ 21 April 2021 However, the agreement seems to have failed to halt the deadly clashes in the region. In April and June 2022, a spate of clashes broke out between Rizeigat militias and Masalit and Gimir ethnic militias in West Darfur, which reportedly led to the killings of hundreds. Thousands of people were also displaced, hundreds of civilian homes burned, and properties looted.4Human Rights Watch, ‘Sudan: New Deadly Attacks in West Darfur,’ 22 June 2022; The Guardian, ‘Sudan: at least 168 people killed in violence in Darfur region, aid group says,’ 24 April 2022; Mohammed Amin, ‘Sudan: Survivors recount horrific details of West Darfur violence,’ Middle East Eye, 26 April 2022 Notably, in late April, a Reizigat ethnic militia attack on al-Kereinik village was reportedly supported by the RSF.5Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese army, RSF clash in West Darfur capital,’ 27 April 2022; Al Jazeera, ‘Who are Sudan’s RSF and their commander Hemeti?,’ 6 June 2019 Deadly clashes were also reported between the RSF and Sudanese military forces in el-Geneina, the capital of West Darfur state.

In neighboring West Kordofan state, political violence events more than doubled in 2022 relative to 2021, while reported fatalities almost doubled, due to increased identity militia activity. The state witnessed the deadliest series of multi-day clashes in Kordofan region in October, when Misseriya ethnic militias backed by the RSF fought with Nuba and Dajo ethnic militias in Lagawa over disputed land. The Nuba and Dajo ethnic militias are linked to rebel leader Abdelaziz al-Hilu’s faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N). Lagawa town was reportedly under the SPLM-N’s control at the time of the violence. The Sudanese government accused the SPLM-N of triggering the clashes, while the SPLM-N refuted being involved in the violence.6Reuters, ‘At least five killed in tribal violence in Sudan’s West Kordofan,’ 16 October 2022 Dozens were reportedly killed and injured, and thousands of civilians were displaced.7International Organization for Migration, ‘Displacement Tracking Matrix | DTM Sudan: Al Lagowa (Al Lagowa Town), West Kordofan,’ 1 November 2022

In Blue Nile state, there was also a significant rise in the number of political violence events and reported fatalities, from nine recorded events and 11 reported fatalities in 2021 to 37 and 487, respectively, in 2022. The state has faced an outbreak of violence between armed ethnic militias, fighting over land access and ownership.8Abdualmoniem Elfaki, ‘What is behind the tribal violence in Sudan’s Blue Nile State?,’ Al Jazeera, 19 July 2022 In July, Hamaj, Barta, and Foung militias on the one hand, and Hausa and al-Falata militias on the other, engaged in week-long fighting, leading to hundreds of reported casualties.9ACAPS, ‘Sudan: Displacement due to conflict in Blue Nile State,’ 28 July 2022 Tensions had increased after the Hausa demanded the creation of a “civil authority to supervise access to land,” which was rejected by the tribal administration, as some local tribes still perceive the Hausa as ‘outsiders.’10Abdualmoniem Elfaki, ‘What is behind the tribal violence in Sudan’s Blue Nile State?,’ Al Jazeera, 19 July 2022; see also Zeinab Mohammed Salih, ‘Hausas in Sudan: The pilgrims’ descendants fighting for acceptance,’ BBC, 23 July 2022 Violence has been fueled by hate speech propagated by tribal leaders vying for political power in the region.11Ayin Network, ‘Violence in Blue Nile – an avoidable crisis,’ 20 July 2022 Deadly violence reignited in September between Hausa and Ingessana ethnic militias after displaced Hausa civilians started returning to their homes.12Sudan Tribune, ‘Seven killed as rival Blue Nile tribes clash again,’ 1 September 2022 Another round of clashes erupted in October in Wad al-Mahi, after two farmers from the Hamaj tribe were reportedly killed, allegedly by Hausa militiamen. Hausa and Ingessana ethnic militias engaged in clashes over two weeks, resulting in at least 250 reported fatalities, hundreds injured, and thousands more displaced.13Mohammed Amin, ‘Sudan: Hundreds killed in ‘atrocities’ as tribal clashes rage in Blue Nile,’ Middle East Eye, 29 October 2022; United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Sudan: Conflict in Blue Nile State, Wad Al Mahi locality, Flash Update No. 06 (24 October 2022),’ 24 October 2022 According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, as of November 2022, “the latest wave of violence has displaced over 97,000 people within the state since July 2022.”14United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Sudan Situation Report, 10 November 2022,’ 10 November 2022 In January 2023, the tribes signed a framework agreement for peaceful coexistence to end the violence and commit to resolving their disputes by peaceful means.15Sudan Tribune, ‘Blue Nile tribal groups agree to end bloody violence,’ 15 January 2023

The power vacuum resulting from the 2021 military coup and the presence of several armed groups – including the Sudanese Armed Forces, the semi-autonomous RSF, and rebel groups – in periphery states, particularly Blue Nile, West Kordofan, and West Darfur, has not only contributed to an escalation of inter-communal violence but also facilitated the rapid increase in the number of ethnic militias.16Jack Jeffery and Samy Magdy, ‘Sudan officials: Tribal clashes kill 170 in country’s south,’ Associated Press News, 20 October 2022; Alan Boswell, ‘A Breakthrough in Sudan’s Impasse?,’ International Crisis Group, 12 August 2022

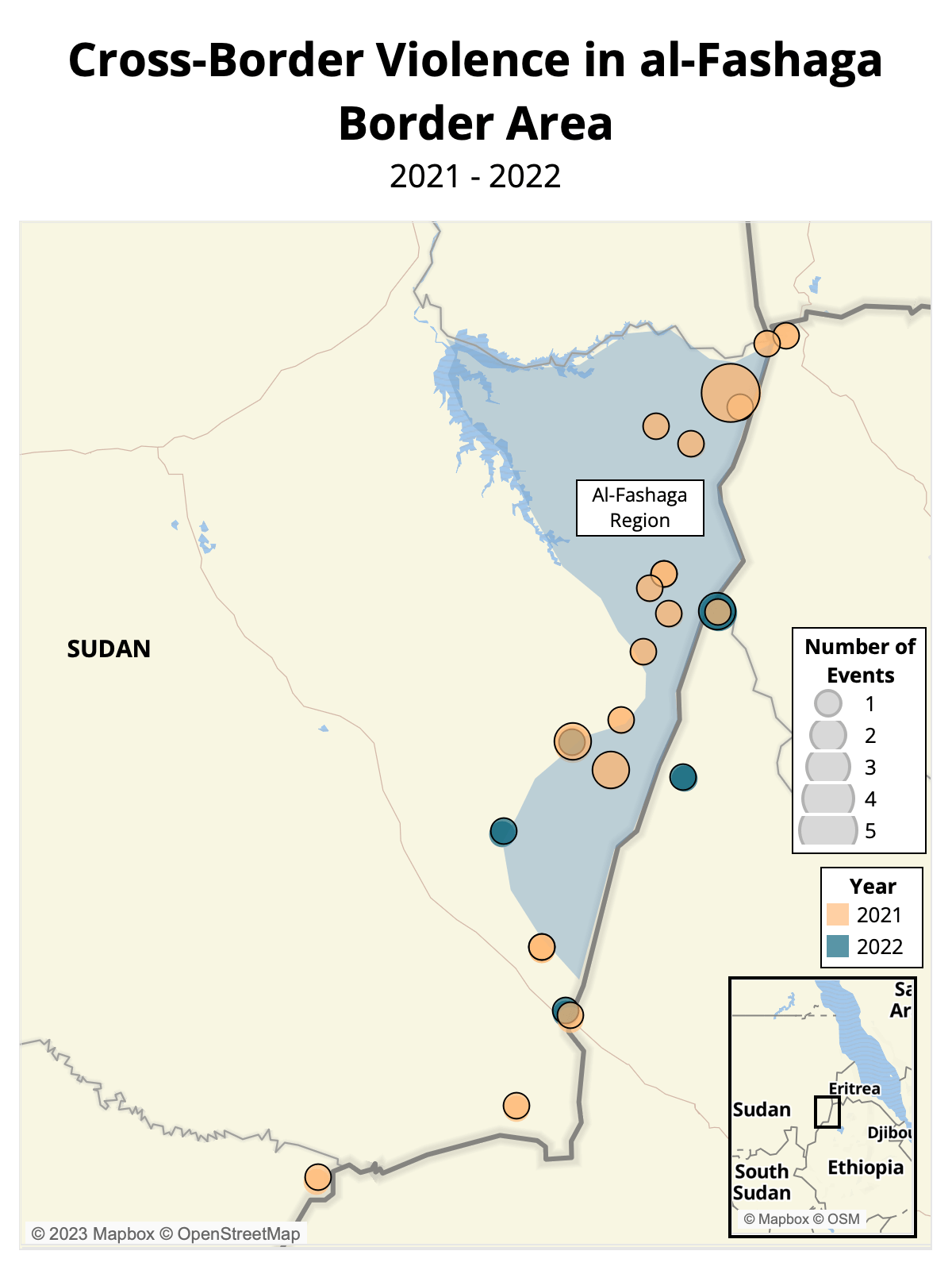

Tensions escalated in June 2022 in the disputed al-Fashaga border area after the Sudanese military accused Ethiopian forces of abducting and executing seven of its soldiers and a civilian, a claim Ethiopia denies.17Mohammed Amin, ‘Sudan launches assault on Ethiopia after alleged executions,’ Middle East Eye, 28 June 2022 The alleged incident triggered the shelling of the areas across the border in Amhara region by the Sudanese military.18Sudan Tribune, ‘Concerns in Sudan over renewed Ethiopian conflict,’ 31 August 2022 Nevertheless, the number of political violence events and reported fatalities in the area overall decreased in 2022 compared to 2021 (see map below). In January 2023, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed visited Sudan for the first time since the military coup in 2021, in what could be a sign of decreasing tensions between the two countries.19Al Jazeera, ‘Ethiopia’s PM Abiy Ahmed in Sudan on first visit since 2021 coup,’ 26 January 2023

Both Sudan and Ethiopia claim ownership of the 260-km2 al-Fashaga borderland, or Mezega area as it is known in Ethiopia, which overlaps the eastern part of Sudan’s ‘breadbasket’ of Gedaref state and the western borders of Ethiopia’s Amhara and Tigray regions. While colonial-era maps officially place the area as part of Sudan, the demarcation of the border has not materialized politically since then. In 2007, former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and the late Ethiopian Prime Minister, Meles Zenawi, signed an agreement authorizing citizens of both countries to farm the land. Before undertaking formal boundary delineation negotiations, though, the two countries’ leadership changed, with Zenawi’s death in 2012 and the ousting of al-Bashir by the popular uprising of 2019. Ensuing turmoil in both countries contributed to subsequent altercations over the area.20International Crisis Group, ‘Containing the Volatile Sudan-Ethiopia Border Dispute,’ 24 June 2021; Alex de Waal, ‘Viewpoint: Why Ethiopia and Sudan have fallen out over al-Fashaga,’ BBC, 3 January 2021

Demonstration activity more than doubled in 2022 relative to the year prior. While the majority of demonstrations were peaceful, intervention by security forces in demonstrations tripled (see graph below), leading to 84 reported fatalities in 2022 compared to 76 in 2021. Khartoum state continued to be the hotbed of unrest, where over three-quarters of all reported fatalities resulting from security force intervention in demonstrations occurred. Sudanese resistance committees – informal neighborhood networks which gained popularity during the demonstrations that led to the ousting of al-Bashir21Nafisa Eltahir, ‘Sudan’s resistance committees take centre stage in fight against military rule,’ Reuters, 2 February 2022 – staged most of these demonstrations. The rallies denounced the military coup, called for a civilian government, and honored those who lost their lives at the hands of Sudanese security forces.

To put an end to the turbulent political landscape in Sudan, after months of negotiations, various political forces, notably the civilian opposition bloc, the Forces of Freedom and Change-Central Council, and the military regime, signed a framework agreement on 5 December 2022.22France24, ‘Sudan’s military, civilian factions sign framework deal aimed at ending crisis,’ 5 December 2022 According to some sources, the deal addresses demonstrators’ demands, such as removing the military’s role in the government and commerce. It also introduces a two-year transition period with a civilian-led government before elections take place.23Ghassan Elkahlout and Sansom Milton, ‘Unblocking the Pathway to Transition in Sudan,’ Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies, 28 December 2022; International Crisis Group, ‘A Critical Window to Bolster Sudan’s Next Government,’ 23 January 2023

Many political actors, however, rejected the new deal. Those opposing the agreement include the Broad Islamic Current, the Democratic Bloc, the Unionist Origin, the head of the Eastern Sudan States Coordinating Council, the Communist Party, the majority of resistance committees, the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, the National Movement Forces, and several former rebel leaders who signed the Juba peace agreement.24Ghassan Elkahlout and Sansom Milton, ‘Unblocking the Pathway to Transition in Sudan,’ Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies, 28 December 2022; Sky News Arabia, ‘Sudan.. What is the framework agreement and who are the supporters and opponents,’ 5 December 2022 Some voiced concern that the new agreement facilitates the continuation of the current stalemate, as it does not address issues such as transitional justice, accountability, and security sector reform.25Hala Al-Karib, ‘Sudan should not settle for anything other than true democracy,’ Al Jazeera, 11 January 2023; Al Jazeera Arabic, ‘Sudan.. Signing of the political framework agreement between the sovereign council and civilian forces,’ 5 December 2022 The Muslim Brotherhood and its allied groups believe that the new agreement pushes “the secularization of the state.”26Sky News Arabia, ‘Sudan.. What is the framework agreement and who are the supporters and opponents,’ 5 December 2022; Abdul Hamid Awad, ‘One week after the signing of the framework agreement in Sudan: deferred issues and relative support,’ The New Arab, 12 December 2022 Critics also claim the new agreement ignores the demands of periphery states, particularly the eastern regions where voices for regional autonomy have increased.27Africa Confidential, ‘History won’t repeat itself,’ 19 January 2023

ACLED will closely monitor the political disorder landscape in Sudan and publish regular country reports exploring and analyzing key trends, including but not limited to:

Interactive Dashboard

< Sudan Hub

Regions:

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) is a disaggregated data collection, analysis, and crisis mapping project.

ACLED is the highest quality and most widely used real-time data and analysis source on political violence and protest around the world. Practitioners, researchers, journalists, and governments depend on ACLED for the latest reliable information on current conflict and disorder patterns.

ACLED is a registered non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status in the United States.

Please contact [email protected] with comments or queries regarding the ACLED dataset.