By David Skilling*

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is now over five months old, an invasion that was initially expected – by the Russians and to an extent by Western intelligence – to take just a few days. Given Russia’s overwhelming military advantage on paper (>10x difference in military spending), this initial assessment was not surprising.

But superior Ukrainian tactics, creativity and bravery, together with Russian incompetence, held the invasion at bay. And now bolstered with Western arms and other assistance, Ukraine has continued to out-perform – fighting the Russians to a de facto stalemate, at least for now.

This has come at an enormous economic and human cost in Ukraine, but it has been a remarkable performance. Although the outlook on the battlefield remains uncertain, with different assessments made of how the momentum is likely to shift over time, Ukraine has a realistic chance of ending this conflict in a reasonable position. And irrespective of how this ends militarily, Russia has been deeply damaged: its strategic position and economic potential have been structurally compromised.

This experience is not unique to Ukraine. Large powers have an imperfect record of successful invasions, from Vietnam to Afghanistan. And through history, academic research shows that small states can beat more powerful states – under certain conditions. An academic study of ~200 conflicts over the past two centuries found that, although large powers tended to beat smaller powers (by ~2:1), this relationship was inverted when small powers adopted innovative tactics (e.g. asymmetric war techniques, such as guerrilla warfare).

In short, the Davids of the world can beat the Goliaths when they adopt different approaches – the scale advantage can be diluted (or reversed) through innovation and creativity. It is sometimes better to be nimble and agile than to have the raw power of a towering giant.

But small powers need to take deliberate action to reverse the surface disadvantage; seriousness is required as well as agility. Indeed, many small states in exposed positions invest heavily in military capability, total defence, and so on (from Finland and the Baltics to Greece and Singapore).

‘In a world where the big fish eat small fish and the small fish eat shrimps, Singapore must become a poisonous shrimp’, Lee Kuan Yew

War by other means

This relationship between scale and performance can be seen in other domains. For example, it is commonly assumed that small economies are disadvantaged relative to large economies: they have smaller domestic markets, fewer resources, are more exposed to external shocks, and so on. But as regular readers will know, this turns out not to be the case.

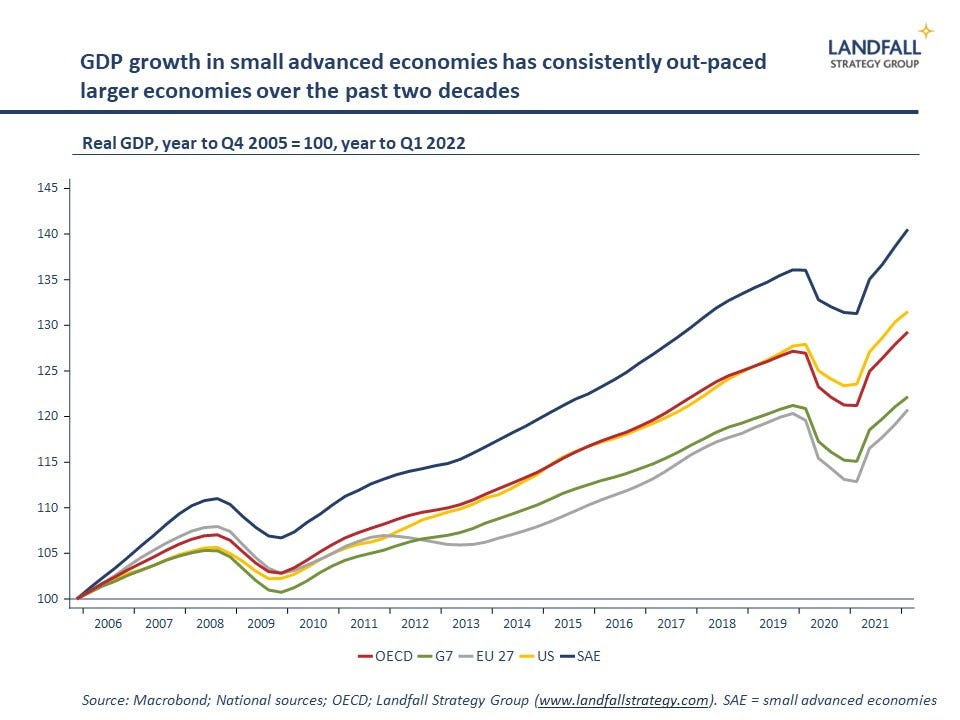

Many obituaries have been written for the small economy model over the past 15 years, commonly after economic shocks like the global financial crisis or due to concerns about the outlook for globalisation. But small advanced economies have continued to consistently out-perform their larger counterparts: they have generated stronger growth through the pandemic (as well as strong health outcomes); over the period since the global financial crisis; as well as over the past several decades.

Although small economies have benefited from a supportive international economic and political environment, the primary reason for small economy success is high quality policy settings – from skills and innovation to macro policy and infrastructure – with a high degree of strategic coherence, supported by effective, agile state institutions.

Being exposed to competitive pressures can be uncomfortable but the imperative to compete in global markets provides a sharpness to small economy actions. For example, small economies have managed the impact of globalisation and technology better than larger economies, designing policy to deliver good outcomes and to retain public support. And small economies produce a disproportionate number of successful, competitive multinational firms.

‘We haven’t got the money, so we’ll have to think’, Lord Rutherford (New Zealand Nobel Laureate).

However, small economies also have limited margin for error. There are multiple examples of small economies that have encountered difficulties, such as Greece and Ireland, after policy mis-steps. And the increasing frequency of idiosyncratic shocks in the post-Covid world will place particular challenges on small economies given their relatively high sectoral concentration levels.

Agility and responsiveness, as well as resilience and an ability to innovate, will be increasingly important attributes of national economic success. Many small economies are well positioned for this.

Thanks for reading small world! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

Diseconomies of scale?

Neither are the effects of scale on outcomes deterministic elsewhere. Consider just a few examples.

Geopolitics is increasingly shaped by big power rivalry, and smaller states can be collateral damage in an increasingly non-rules based world. But smaller countries also have an ability to stay out of the way. It was the direct protagonists in the US/China trade wars that suffered the biggest losses. And although China often squeezes other economies that it has disputes with, this is as often with larger economies (Japan, South Korea) as small economies (Lithuania, Norway).

Large economies can advance their interests through raw power; but that doesn’t always deliver good outcomes. Creative, agile diplomacy can allow smaller states to manage their exposures and to continue to prosper (Singapore, Switzerland).

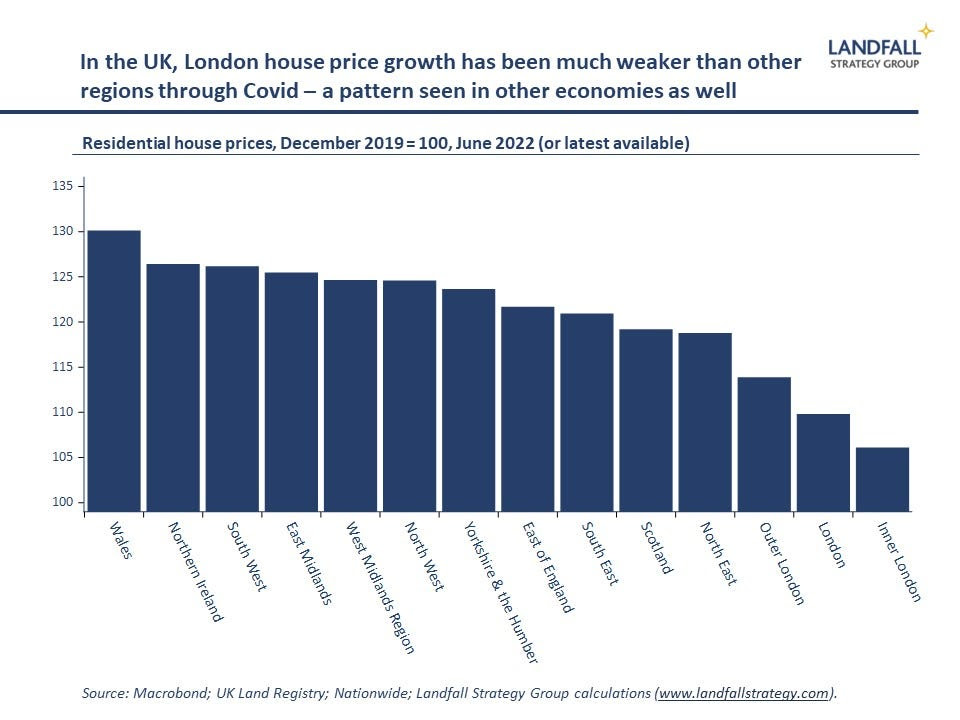

In another domain, there are shifts in economic geography in the post-Covid world – with some evidence of people/firms relocating away from large hubs (New York, San Francisco, London) to smaller cities or regions. The use of technology during the pandemic, coupled with shifting preferences, has loosened the hold of large cities.

Population growth shows this, as does variation in patterns of house prices/rentals in a number of advanced economies from Japan to Canada, the US and the UK. Large cities will remain important, but agglomeration forces are likely to weaken.

In terms of firms, the empirical evidence suggests a positive relationship between firm scale and productivity, exporting, capital intensity, and so on. And numerous studies find that industry concentration has increased, with a smaller number of large firms dominating areas of the economy and earning economic rents. There is a winner take all dynamic, particularly in the technology space (Amazon, Google, and others).

However, many of these now-large firms are young, and either created new industries or displaced incumbents. During the pandemic, new firms like Moderna and BioNTech were central to successful Covid vaccines. Scale has been a function of success, not the other way around.

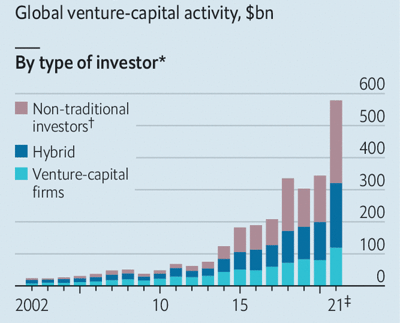

Creative destruction in the listed company space remains high, and start-up rates and IPOs are also healthy. Over the past decade, substantial amounts of venture capital has gone into funding the next big thing in Silicon Valley and beyond (note a good book by Sebastian Mallaby on the VC industry). Some of this has been juiced by low interest rates over the past decade, but the point remains that small, young firms remain an important source of economic dynamism.

So for all of the plausible talk of the advantages of scale (US, China, Amazon, etc), success does not necessarily belong to the large.

Survival of the fittest

We are likely to be moving into a period of elevated economic and political volatility. Scale is a useful lens to think about which countries and institutions are most likely to prosper in this environment.

‘It is not the strongest or the most intelligent who will survive but those who can best manage change’, Charles Darwin

Scale can buffer against shocks, but can also make change more difficult. Smaller states and firms, which are deeply exposed to external dynamics, are often well-positioned to respond to these changes – they sense change quickly, have agile decision-making, and often have helpful levels of paranoia about the competitive environment.

Even after the destruction wreaked on Ukraine, I would put my money on Ukraine’s long term performance over Russia. And more broadly, I expect disproportionately strong performance from smaller economies.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original article is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

Your access to our unique and original content is free, and always has been.

But ad revenues are under pressure so we need your support.

Supporters can choose any amount, and will get a premium ad-free experience if giving a minimum of $10/month or $100/year. Learn more here.

become a supporter

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don’t welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.

Encouraging David, thank you. We just need some decent leadership now & we’ll be away.

Why wouldn’t we just take our own initiative instead of waiting for some supreme leader.

If ACT & TOP were the #1 and 2 political party’s we’d be sorted … sadly , our choices are Ardern or Luxon … rat sandwich with tomato sauce , or rat sandwich with mustard … blahhhhh….

No one I know who’s been overly successful has needed a regime change to do so.

Is there no other online outlet for people to incessantly complain about the government in NZ? Doesn’t Stuff have a comments section.

Stuff comments only speak woke

… yes , they have a preset list of parameters which you must 100 % agree to ( pakeha bad / maori good / climate change 100 % mankind’s fault / older white men are evil / etc etc ) or your comment will not be shown …

There certainly seem to be a fair share of Talkback Boomers and Facebook Angries on there too, and those that span both.

I have been in business in New Zealand and Australia for over 40 years. Never recall a business decision that was influenced by the flavour of government of the time.

… great article , David … it reminds me of the quote : ” Elephants don’t gallop ” …

But … poor old NZ , is mired in social welfarism , as successive Labour governments unwind the excellent work done by their predecessor Sir Roger Douglas … and the Gnats are too gutless to block or to undo the damage done successively by Cullen & Robertson …

… where’s me $ 116 , Robbo … you promised !

It’s easy to lose sight of some of the benefits of being smaller.

I remember going to Japan (late 90s), a country that to me seemed ahead in technology, and being surprised their banking system was still cash based, no EFTPOS in stores, and ATMs that went offline for the weekend on a Friday afternoon. Because while the Japanese have an engineering philosophy of constant improvement, many of their larger institutions are bogged down in rigid formalities. It’s improved now, but it took a while.

Likewise NZs internet, is relatively quick and cheap for a country of our size, geography and demographics. The US by comparison has quite varying access/coverage.

NZ is never going to compete at many, many fields and aspects. Small country quite a distance from a lot of larger markets. Always play to your strengths rather than try be all things to everyone

Access to working capital is probably one of our biggest hurdles, but given the risk also difficult to address.

…superior Ukrainian tactics, creativity and bravery, together with Russian incompetence, held the invasion at bay.

To be honest Russian corruption did a lot of the donkey work. Russian Defence Minister, Sergei Shoigu, deserves some sort of NATO medal for being able to make hundreds of billions disappear without any tangible benefit to the Russian military.

… it is astonishing , that in some instances they have world leading science & medicine …first man in space / first Covid19 vaccine ….

And yet , at other times they appear to be complete vodka riddled brain damaged dingbats …

.. unlike the Chinese & the Brits or the Americans … ahem ! … yeah , right …

“Ukraine has a realistic chance of ending this conflict in a reasonable position”

What a load of nonsense.

Ukraine will probably be rendered a failed state on account of the war. It’s economy is basically disappearing into nothing. There is currently 35% unemployment. All state affiliated institutions are in the process of defaulting on there debt. The currency is being devalued at an increasingly fast pace. They currently have 30% inflation, gdp has halved. They don’t Have any gas for winter they need 10 billion to buy it on the spot market. Who will give them this money? Wheat farmers won’t plant for the next year as there is too much uncertainty around whether they will be able to both physically harvest and ship next year. There will be massive permanent depopulation over the next year as things only get worst….

Sorry for ranting but this whole Ukraine will be alright in the long term is complete baloney…

Alright? Depends on your definition of alright, I guess? My definition of alright for Ukraine would go something like beating off the Russian invasion and prevent another 50 years of rotting under the psychopathic Kremlin kleptocracy. Degrees of “alright” are increasingly rosey the greater the distance from sub human Russian leadership.

I’d say in this context, a “reasonable position” is roughly equivalent to “still exists”

The west will have to keep increasing it’s involvement in the war to push Putin back. If he gets Ukraine he won’t stop there….

We noticed that you’re using an ad blocker. Or, your browser is blocking ad display with its settings.

Your access to our unique and original content is free, and always will be.

Please help us keep it that way by allowing your browser to display ads. How?

OR,

Create a SUPPORTER account with no ads here.

If you’re already a Supporter, please use the Supporter Login option here.

The calculations in this tool are controlled by interest.co.nz.

Terms & Conditions apply to every loan.