Read The Diplomat, Know The Asia-Pacific

China’s role in lending to Sri Lanka has expanded in the last 20 years, but fewer Chinese loans would not have saved the country from its current economic crisis.

China has never been Sri Lanka’s biggest lender. Nevertheless, as Sri Lanka has fallen into economic woes, particularly in the wake of COVID-19, blame has turned to China. However, Sri Lankan officials have repeatedly expressed the view that China is not the source of the country’s economic woes. So what’s the real story?

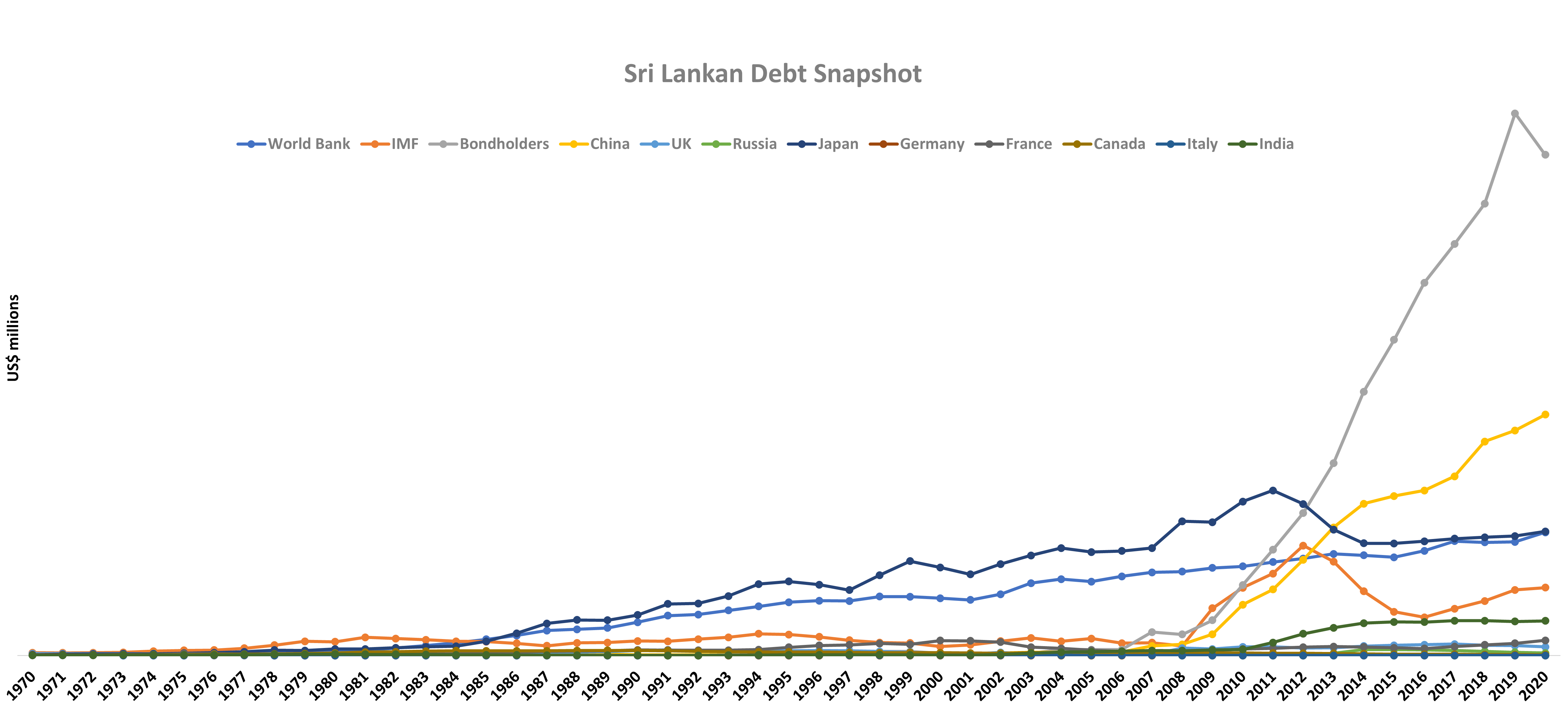

China has certainly featured more in Sri Lanka’s economy over the last few years. Back in the early 1970s, Sri Lanka borrowed around 4 percent of its loans from China, and borrowed more from the U.K., Japan, and Germany, at around 17 percent, 8 percent, and 6 percent respectively. At that time, Sri Lanka also borrowed more from the IMF and World Bank – they accounted for around 25 percent and 9 percent, respectively, of the island country’s foreign debt.

Fast forward to 2020 and that profile had shifted somewhat. Japan and the World Bank remained significant lenders at 7 percent each, but the IMF’s proportion had shrunk to just 4 percent, as had the U.K. and Germany, which then accounted for around 1 percent of Sri Lanka’s debt. They had been replaced by commercial lenders (“bondholders”) at 29 percent and China at 14 percent.

Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific.

How did this shift come about and what does it suggest about the role of China in Sri Lanka’s current debt woes?

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Sri Lanka – which defaulted on its sovereign debt in May, the first Asia-Pacific country to do so in more than two decades – has not faced an easy economic journey since the 1970s, despite being at some points seen as an exciting, growing market.

Between 1983 and 2009 Sri Lanka went through a civil war, the roots of which extend back to the colonial era when the country was known as Ceylon. Over the civil war period, Sri Lanka’s debt levels in absolute terms rose steadily, especially from the World Bank and Japan, and the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio swung up and down depending on the growth impacts of the war. Nevertheless, economic growth was fairly positive, and poverty rates declined from 26.1 percent in 1990-91 to 15.2 percent in 2006-07. The country was on course to attain the Millennium Development Goal target of halving poverty at the national level by 2015.

Given the consistent growth, although Sri Lanka was deemed a “serious concern” in 2005 under the World Bank and IMF’s new debt sustainability framework and ruled in 2006 to be technically eligible for debt relief through the Highly Indebted Poor Countries’ Initiative (HPIC), along with Bhutan, Laos, Kyrgyzstan, and Nepal, Colombo decided not to avail itself of the relief. Sri Lanka similarly did not seek debt relief from China. Further, as tensions reduced domestically, the government began to take steps to try to further improve Sri Lanka’s economic situation by raising new debt and stimulating growth. This is where a new shift began that explains some of the present-day dynamics.

From 2007 onward, seeing growth in the agriculture, industrial, and tourism sectors, Sri Lanka presented itself as an exciting new destination for global investment, and started to borrow more than ever, in a rational attempt to convert the growth into further productivity through investment in infrastructure projects that had seemed impossible previously. For instance, in 2007, pre-dating the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Sri Lankan government announced the idea to build a port in Hambantota near the Indian Ocean shipping lane that accounts for more than 75 percent of the world’s marine-borne trade. Forecasting a growing middle class in Africa and India and a growing demand for Chinese goods, Sri Lanka wanted to snag a proportion of cargo that would otherwise go through Singapore – the world’s busiest transshipment port. China Harbor Group eventually built the port by 2010; it was funded using a 15-year loan of $307 million with a grace period of four years, and a fixed interest rate of 6.3 percent, from China Eximbank. There are other such examples of lending from China.

Alongside this vision, global conditions for private sector borrowing improved. After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, interest rates reduced, and with a “moderate” debt label from the multilaterals Sri Lanka looked to international sovereign bonds to further finance spending. Local consumption rose, even though international trade was not necessarily rising. Therefore, despite growth and poverty reduction, Sri Lanka started to become what is known as a twin deficit economy – an economy that imported more than it exported, and spent more than it was generating.

This might have been a fine strategy if it were not for external shocks. In 2016 and 2017 Sri Lanka experienced a sharp decline in growth, which dropped to the lowest level since 2001 due to repeated floods and drought. Then a series of bomb attacks on Easter Sunday in 2019 cut tourism. In a bid to stimulate economic activity, and as had been promised in the presidential campaign, the government implemented some drastic tax cuts across all sectors of the economy in late 2019. These cost the government close to 800 billion rupees ($2.2 billion). However, before the tax cuts could begin stimulating the economy, COVID-19 hit, ravaging the tourism sector, a major source of income. COVID-19 also required increased spending and increased imports of health and other products, exacerbating the trade deficit.

Foreign currency reserves dropped by 70 percent, meaning less dollars to purchase essential yet increasingly expensive imports including fuel and commodities. To solve this, the government encouraged local spending – for example, on locally sourced fertilizer rather than imports of non-organic fertilizers, which were also having adverse environmental and health effects – and printed money, as many richer countries did. However, these moves all had the effect of increasing inflation – which reached 60 percent by June 2022 – while farmers ran low on fertilizers, seeds, and pesticides to grow their produce.

Given all this, a key question is whether less lending from China – or any other lender – would have made much difference to Sri Lanka. The answer is unclear, but it seems unlikely, given China’s fairly limited role in Sri Lanka’s overall debt levels. In addition, the fact is, countries such as Sri Lanka need more finance – not less – to build infrastructure to develop diversified, efficient and growing economies, and escape the kinds of traps the country has found itself in.

Looking forward, what role can China or other lenders play now, if any?

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Classified as a middle-income country, Sri Lanka is not eligible for the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative nor its Common Framework – both of which China is part of. The Sri Lankan government has explored an IMF bailout, but the IMF has said it cannot help until there is “adequate financing assurances from Sri Lanka’s creditors that debt sustainability will be restored.” This is similar language to what the IMF has used regarding Zambia (who is eligible for the Common Framework). As a veiled reference to China, the IMF’s language suggests that if China does indicate willingness to restructure existing Sri Lankan debt to other creditors, the IMF could provide a bailout.

That said, an IMF bailout will come with its own challenges. The IMF has already indicated it will encourage austerity in Sri Lanka – reducing spending and increasing taxes. Sri Lanka did not seek debt relief in the 1990s or early 2000s for a reason. Furthermore, an IMF bailout will not reduce debt service to Sri Lanka’s largest lenders, bondholders.

But Sri Lanka can still use its relationship with China in a way that more directly helps address the crisis.

The first step is for Sri Lanka to formally request meetings with China to discuss payment reductions, beyond DSSI. All dollars or renminbi saved will count. The second step is to meet with other borrowers finding themselves in similar situations – such as Zambia and Ghana – to strategize about how to manage both China and other lenders, including multilaterals and the private sector. Ultimately, reform of the international financial architecture is needed to ensure borrowers such as Sri Lanka can weather external shocks while still spending necessary finance on development.

Finally, it is key for Sri Lanka to work with China and other large economies explore how to reignite growth, while learning from the mistakes of the past and avoiding a dual track economy. China – as a large global exporter and importer – can be a partner in that, but it will take work, and a new emphasis in the relationship.