2 August 2023

Image: Homes destroyed by Russian strikes in eastern Ukraine, 2023. © Виктория Котлярчук / Adobe Stock

Drawing on the latest ACLED data, this report analyzes key trends in Wagner Group activity across the globe, with an in-depth focus on the mercenary organization’s operations in Ukraine, the Central African Republic, and Mali.

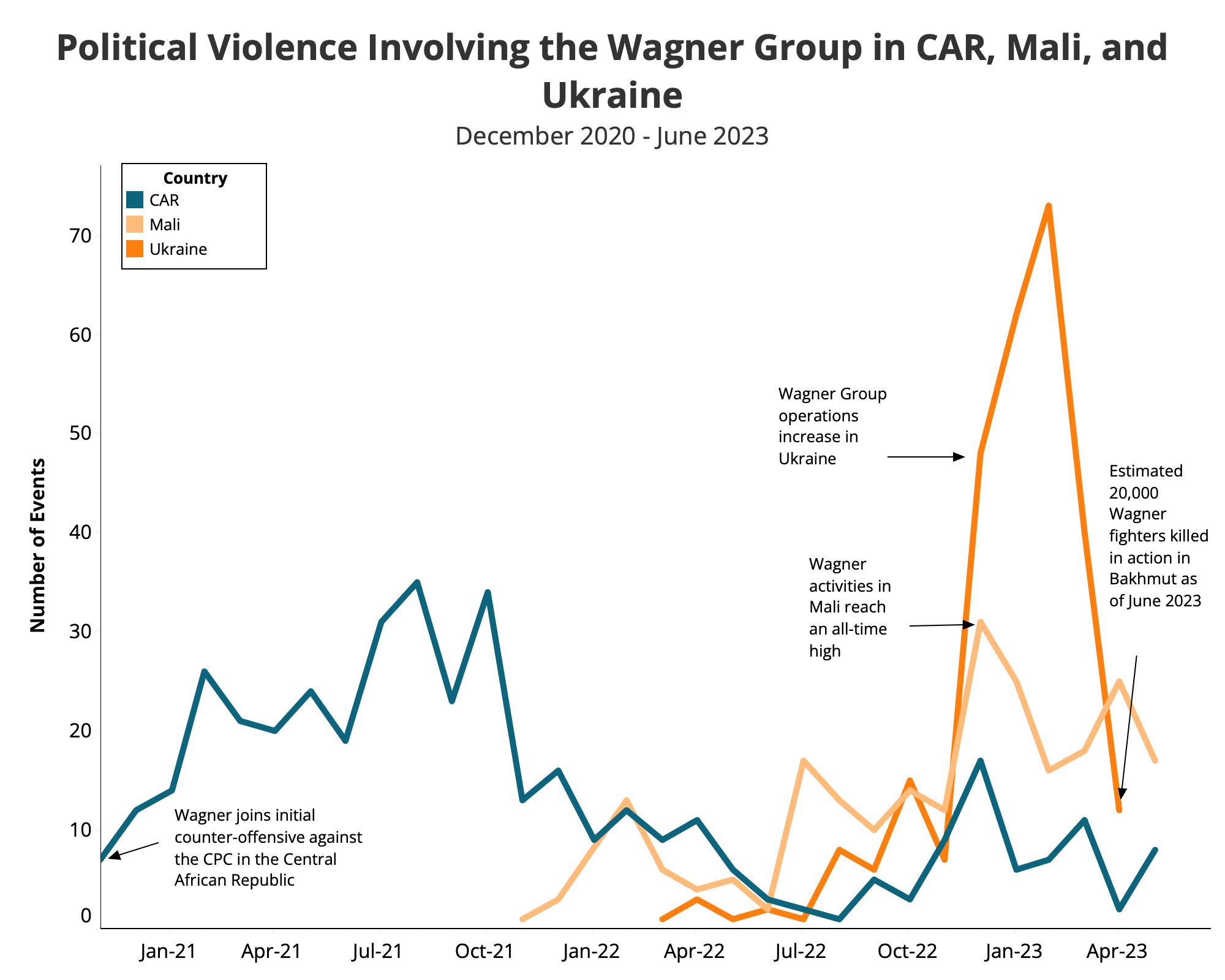

The Wagner Group’s move towards a public profile in September 2022 was followed by an escalation of its operations in multiple major theaters of conflict, including the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, and Ukraine. Before Wagner’s attempted march on Moscow in June 2023, conflict incidents involving the group this year had already surpassed the total recorded for all of 2022. Likewise, in the first quarter of 2023, Wagner violence rose in CAR, Mali, and Ukraine relative to the average number of quarterly events for the previous year. Amid the overall growth in violent activities attributed to Wagner, this report examines the organization’s military operations worldwide, with case studies analyzing key trends in CAR, Mali, and Ukraine.

Common understandings of the Wagner Group tend to over-emphasize its military strength or focus on the ineffectiveness of its mercenary troops. Instead, this report illustrates how its military capacity and operations vary significantly across different conflict theaters. The Wagner Group has proven capable of suppressing two rebel offensives in CAR, but faced challenges when confronting jihadist militants in Mali and opposing military forces in Ukraine. When Wagner holds technological advantages against opposition forces during traditional military engagements, such as in CAR or in Libya, its operations have often been effective. However, when fighting with insurgent groups, as in Mali or in Mozambique, as well as when facing similar or superior military capacity, as in Ukraine, the Wagner Group has seen much more limited success.

These differences are also explained by the composition of its mercenary troops. Wagner’s primary competitive advantage in Ukraine was the Russian government’s approval of recruitment among the country’s vast prison population. Former prisoners were subsequently deployed and often sent into ‘human wave’ attacks on Ukrainian defense lines with high levels of reported fatalities. This is substantially different from Wagner in Africa, where fighters are often better trained and less expendable. These inconsistencies show neither a unified, powerful arm of the Russian state nor an ineffective criminal actor. Instead, analysis of Wagner operations reveals a mix of economic motivations influenced by their political connections with the Russian military, and a capacity for violence varying over time and by location.

The longstanding support of the Russian state for Wagner belies a more ambivalent relationship. Tense relations between Wagner and Russia’s Ministry of Defence preceded the all-out war in Ukraine and date back to the group’s involvement in the conflict in Syria in 2018. These tensions occasionally escalated into internecine fighting between Wagner mercenaries and Russian military forces. ACLED records multiple clashes between Wagner fighters and other Russian units before the march towards Moscow in June 2023. Yet, not long before, Russian President Vladimir Putin had congratulated the Wagner Group for their role in taking over Bakhmut1Kremlin.ru, ‘Vladimir Putin Congratulates Russian Military with the Liberation of Artemovsk,’ 21 May 2023 and admitted to extensive financing of the organization.2Reuters, ‘Wagner leader Prigozhin to be investigated for $2 billion pay in a year, Putin says,’ 28 June 2023; Russian News Agency, ‘Putin says Wagner group fully financed by Russian government,’ 27 June 2023

Drawing on ACLED data on Wagner Group military engagements around the world, this report also further documents the organization’s role in violence against civilians, including attacks targeting specific civilian groups. In addition to direct attacks on civilians perpetrated by Wagner, this report also tracks the threat to civilians posed by the group’s recruitment activities and the support it provides to other non-state armed actors. These Wagner-trained militias engage in high levels of civilian targeting and generate spillover risks for neighboring countries, exemplified by Wagner support for Chadian armed groups in CAR that have since carried out cross-border attacks.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Wagner Group has pivoted from a more secretive organization with limited public engagement to a publicly recognized and front-facing part of Russian foreign influence. This shift included prominent Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin accepting responsibility for creating the Wagner Group in 2014 to support Russian separatist fighting in eastern Ukraine after long denying ties to the group.3On 26 September 2022, Prigozhin took public credit for creating the Wagner Group after years of denying involvement with the organization, marking a clear shift from the former secretive nature of the Russian private mercenary company. See Pjotr Sauer, ‘Putin ally Yevgeny Prigozhin admits founding Wagner mercenary group,’ The Guardian, 26 September 2022 The elusiveness of Wagner’s early engagement has been traded for social media campaigns, public statues,4For example, the Russian military statue in Bangui and Crimea featured in Elian Peltier, ‘Xi Condemns Killings in African Nation Where Russian and Chinese Interests Compete,’ New York Times, 20 March 2023 and John Haines, ‘How, Why, and When Russia Will Deploy Little Green Men – and Why the US Cannot,’ Foreign Policy Research Institute, 9 March 2016 open calls for recruits,5All Eyes On Wagner, ‘Recruitment campaigns in Ukraine and Africa/Middle-East,’ 17 March 2022 identifiable offices in St Petersburg, and strong criticism from Prigozhin towards Russian military officials.6Shane Harris and Isabelle Khurshudyan, ‘Wagner chief offered to give Russian troop locations to Ukraine, leak says,’ Washington Post, 15 May 2023; The Economist, ‘Why the boss of Wagner Group is feuding with Russia’s military leaders,’ 11 May 2023 Verbal criticism from Prigozhin eventually turned to a short-lived rebellion against Russian military officials on 23 June 2023 (see section below on Wagner Invades Russia (for a Day)).

Following ACLED’s previous report on Wagner operations in Africa, published in August 2022, the epicenter of political violence involving the Wagner Group has shifted from Africa – primarily Mali and CAR – towards Europe and the conflict in Ukraine. This shift is not, however, indicative of declining Africa operations. Indeed, in the first quarter of 2023, violent events involving the Wagner Group rose in the major areas of conflict – Mali and CAR – from the average number of quarterly events over the previous year (see graph below). With a more public profile, information on the Wagner Group has also grown tremendously and shows different typologies of global operations, including political, economic, and military engagement.7Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon, and Julian Rademeyer, ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa,’ Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, February 2023; See video footage in Benoit Faucon, ‘U.S. Intelligence Points to Wagner Plot Against Key Western Ally in Africa,’ Wall Street Journal, 23 February 2023 By April 2023, conflict events involving the Wagner Group globally, and the estimated fatalities arising from such activity, already surpassed the total for the entire previous year.

Following the armed rebellion of 23 June, Russian President Putin claimed that the Wagner Group and Prigozhin’s catering company, Concord, had received a total of nearly 2 billion US dollars from the Russian government.8Reuters, ‘Wagner leader Prigozhin to be investigated for $2 billion pay in a year, Putin says,’ 28 June 2023; Russian News Agency, ‘Putin says Wagner group fully financed by Russian government,’ 27 June 2023 Yet, Wagner’s direct operations against Russia show evidence of a more ambivalent relationship with the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD), particularly the military intelligence service (GRU).9Kimberly Marten, ‘Where’s Wagner? The All-New Exploits of Russia’s “Private” Military Company,’ Ponars Urasia, 15 September 2020; Alex Thurston, ‘Wagner Group accused of plotting a ‘confederation of states’ in Africa,’ Responsible Statecraft, 2 May 2023; See also United States State Department classification cited in Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021, page 6

This report updates and expands previous ACLED research by examining the Wagner Group’s military operations across three major theaters of conflict: Ukraine, Mali, and the CAR. The report analyzes ACLED data in relation to each case study, examining the overall growth in Wagner’s conflict activity and the main political and military developments until June 2023. In doing so, it questions overstated or inaccurate representations of Wagner operations as either a mere extension of the Russian MoD a failure or as a largely ineffective mercenary company.10See for example Daniel Sixto, ‘Russian Mercenaries: A String of Failures in Africa,’ Geopolitical Monitor, 24 August 2020; Federica Saini Fasanotti, ‘Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa: Influence, commercial concessions, rights violations, and counterinsurgency failure,’ Brookings, 8 February 2022; Anthony Loyd, ‘Diamond-rich African country is a zombie host for Wagner Group,’ The Times, 19 May 2023; Jason Blazakis, ‘Written evidence submitted by Jason Blazakis (WGN0023),’ United Kingdom Foreign Affairs Committee, October 2022

This report shows that Wagner operations in CAR proved capable of suppressing offensives by rebel groups but faced limitations when confronting jihadist militants and Ukrainian military forces. When the Wagner Group holds technological advantages against opposing armed groups during traditional military engagements, such as CAR or Libya, it has shown effectiveness in suppressing opposing forces. However, when fighting with insurgent groups, as in Mozambique and Mali, or when facing similar or superior military capacity, as in Ukraine, the Wagner Group had more limited success. Drawing on Wagner’s military engagements, the report emphasizes the ongoing trend of civilian targeting but shows that the majority of civilian targeting has taken place in Mali and CAR. These findings pose further policy implications to better understand the risks and trade-offs involved in responding to the Wagner Group.

Despite the sizable media profile of its founder, Yevgeny Prigozhin, early Wagner operations are shrouded in mystery. The group is commonly believed to be the brainchild of the GRU, composed of former commando fighters and formed to ensure deniability of Russian covert operations in eastern Ukraine and beyond.11Andrei Soldatov and Irina Bologan, ‘Why Putin Needs Wagner,’ Foreign Affairs, 12 May 2023 The link to GRU is circumstantially confirmed by the fact that Wagner’s operational leader, Dmitriy Valeryevich Utkin, is a Ukrainian-born retired member of the GRU special forces,12Mary Ilyushina, ‘In Ukraine, a Russian Mercenary Group Steps out of the Shadow,’ Washington Post, 18 August 2022 who is believed to harbor neo-Nazi leanings and to have conferred his ‘Wagner’ call sign to the entire formation.13Denis Korotkov, ‘Heil Petrovich,’ Dossier Center, 10 April 2023 Another theory suggests that the Wagner Group may have been created with the blessing of the Russian General Staff – a top operational body in Russia’s armed forces.14The Bell, ‘Army for President. The Story of Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Most Delicate Assignment,’ 29 January 2019

Several reports link Prigozhin – a St Petersburg-born convicted criminal and catering entrepreneur – to an overlapping network of businesses and private military forces with alleged links to the Kremlin.15Amy Mackinnon, ‘What Is Russia’s Wagner Group?,’ Foreign Policy, 6 July 2021; Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon, and Julian Rademeyer, ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa,’ Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, February 2023; Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021 For several years, Prigozhin denied any links to private military companies (PMCs) but kept close ties to Russian President Putin and Russian military intelligence.16Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021 Although initially denied, both Prigozhin and the Russian authorities now accept the existence of the Wagner Group.17The Sentry, ‘Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,’ June 2023

The increasingly public image of the Wagner Group goes against many understandings of the very point the group came to exist during their initial deployment in Ukraine.18Mary Ilyushina, ‘In Ukraine, a Russian Mercenary Group Steps out of the Shadow,’ Washington Post, 18 August 2022; Tad Schnaufer, ‘Redefining Hybrid Warfare: Russia’s Non-linear War against the West,’ Journal of Strategic Security, Spring 2017’; Kimberly Marten, ‘Where’s Wagner? The All-New Exploits of Russia’s “Private” Military Company,’ Ponars Urasia, 15 September 2020 Military and security strategists pointed to new forms of Russian engagement around hybrid or non-linear warfare, but the underlying desire for Russia to permit the Wagner Group and other PMCs to operate illegally and deny links to the group was theorized as a strategic way for Russia to distance itself from certain activities.19Tad Schnaufer, ‘Redefining Hybrid Warfare: Russia’s Non-linear War against the West,’ Journal of Strategic Security, Spring 2017 Now that the links between the Russian government and the Wagner Group are publicly acknowledged, further questions arise about the underlying reason for this new phase of warfare.

Emerging evidence also shows a more ambivalent relationship between the Russian state and the Wagner Group. Russian military forces have taken credit for Wagner Group victories alongside clear public disagreements and a short attempt to replace strategic military leadership. Recent reports further note the variation in command structure between Russian military forces and the Wagner Group, drawing into question previously held understandings of Wagner as an extension of the Russian military.20Kimberly Marten, ‘Where’s Wagner? The All-New Exploits of Russia’s “Private” Military Company,’ Ponars Urasia, 15 September 2020 Further disparities show both former elite Russian military soldiers and officers being recruited and drawn into the Wagner Group, alongside the recruitment of inexperienced prisoners.21All Eyes On Wagner, ‘Recruitment campaigns in Ukraine and Africa/Middle-East,’ 17 March 2022 Evidence of skilled, yet sometimes underequipped, mercenaries emerged in Libya,22Nader Ibrahim and Ilya Barabanov, ‘The lost tablet and the secret documents,’ BBC News, 11 August 2021 but widespread evidence points to recent recruits drawn amongst ex-convicts who were given low training.

The varied support between the Russian state and the Wagner Group, along with indications of mixed recruitment, provides further confirmation of variation within the Wagner Group. Some units may be highly trained and engage in more advanced operations, while others are used for human wave offensives. These inconsistencies show neither a unified, powerful arm of the Russian state nor an ineffective criminal actor. Instead, Wagner Group operations illustrate a mix of economic motivations influenced by their political connections with the Russian military, with a capacity for violence varying over time and by location.

In 2014, Russia armed separatist proxy forces and deployed PMCs to incite an armed rebellion in eastern Ukraine. These PMCs were variously linked to elements of Russia’s military and economic establishment, allowing Russia to project its hard power while claiming plausible deniability. Among them was the Wagner Group, which gradually pivoted elsewhere in political, economic, and military campaigns.23Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021 Over the years, the Wagner Group has engaged in disinformation campaigns and election interference, provided military and security services to several governments, and signed contracts to exploit natural resources, often through companies linked to Prigozhin.24Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon, and Julian Rademeyer, ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa,’ Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, February 2023; Proekt, ‘Master and Chef. How Russia interfered in elections in twenty countries,’ 11 April 2019; Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021

After involvement in Ukraine, information emerged on Wagner Group’s activities, with reports of Wagner Group engaging in conflict in Syria by late 2015 to support Bashar al-Assad’s regime in exchange for a percentage of proceeds on oil and gas production fields taken back from the Islamic State.25Robert Hamilton, Chris Miller, and Aaron Stein, ‘Russia’s War in Syria: Assessing Russian Military Capabilities and Lessons Learned,’ Foreign Policy Research Institute, 15 October 2020 In Syria, Wagner mercenaries have engaged directly in conflict on numerous occasions against Islamic State militants, as well as a high-profile and much-debated offensive against a Syrian Democratic Force position with United States military support at a Conoco station near Khasham, Deir ez-Zor governorate, resulting in Wagner fatalities following artillery and airstrikes by US military forces.26Christoph Reuter, ‘The Truth About the Russian Deaths in Syria,’ Spiegel, 2 March 2018; Ishaan Tharoor, ‘The battle in Syria that looms behind Wagner’s rebellion,’ Washington Post, 30 June 2023 The longstanding operations in Syria have also provided a strategic base for Wagner operations elsewhere, including personnel recruitment for fighting in other countries.27Jason lazakis, Colin Clarke, Naureen Chowdhury Fink, and Sean Steinberg, ‘Wagner Group: The Evolution of a Private Army,’ The Soufan Center, June 2023

Elsewhere, Wagner mercenaries engaged in direct conflict in CAR, Mozambique, and Libya between 2017 and 2019.28Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021; later dates in Mozambique considered by Borges Nhamirre, ‘Will foreign intervention end terrorism in Cabo Delgado?’ Institute for Security Studies, 5 November 2021 Some of these military deployments were short-lived, including attempts in Mozambique to send a few hundred fighters alongside military forces to curb the Islamist insurgency in Cabo Delgado.29Kimberly Marten, ‘Where’s Wagner? The All-New Exploits of Russia’s “Private” Military Company,’ Ponars Urasia, 15 September 2020 Reports suggest that Wagner was deployed between October 2018 and September 2019, withdrawing between November 2019 and March 2020 after taking on significant losses to Islamist militants and losing the government contract to the Dyck Advisory Group, a South African-based PMC.30Daniel Sixto, ‘Russian Mercenaries: A String of Failures in Africa,’ Geopolitical Monitor, 24 August 2020; Kimberly Marten, ‘Where’s Wagner? The All-New Exploits of Russia’s “Private” Military Company,’ Ponars Urasia, 15 September 2020; Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021, p. 60

In Libya, the Wagner Group, Rossiskie System Bezopasnosti Group – another Russian PMC – and Russian military special forces supported General Khalifa Haftar and the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA).31Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021, p. 42 – 43 Russian PMCs set up bases and have provided military support since 2016 to bolster the LNA, providing further equipment, training, and intelligence services.32Seth Jones et al, ‘Russia’s Corporate Soldiers: The Global Expansion of Russia’s Private Military Companies,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2021, p. 16 As in other countries, Wagner operations in Libya have been closely tied to oil and gas resources.33Robert Uniacke, ‘Libya Could Be Putin’s Trump Card,’ Foreign Policy, 8 July 2022

Widespread direct engagement in conflict in Africa began in late 2020 and early 2021. The Wagner Group was reported to be fighting in CAR to defend the ruling government from an offensive by the Coalition of Patriots for Change (CPC) rebel coalition. One year after Wagner escalated military operations in CAR, the group began taking a more direct military role in Mali, upon invitation from the government in December 2021.34Violent events involving Wagner Group in Africa dropped in February 2022 following the invasion of Ukraine, trending downwards and reaching the lowest levels of reported violence in July 2022. Some explain this drop in events to a withdrawal of Wagner forces from Africa to Ukraine, see Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon, and Julian Rademeyer, ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa,’ Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, February 2023, p. 8

In addition to increasing direct involvement in violence, the information environment surrounding Wagner has dramatically shifted from the initial limited reporting. Early reports in Ukraine, Mozambique, Libya, and CAR simply discussed “Russian,” “green men,” or “white” military trainers, sometimes difficult to discern from Russian military forces.35John Haines, ‘How, Why, and When Russia Will Deploy Little Green Men – and Why the US Cannot,’ Foreign Policy Research Institute, 9 March 2016 Further information emerged of identifiable distinctions between Russian PMCs and Russian special forces, including photographic evidence of mercenaries linked to Prigozhin and connections with Prigozhin-linked businesses. In several areas, the increasingly public profile and growing evidence permits clearer attribution of the Wagner Group within the ACLED dataset (see further discussion in each case study below). Contrasting earlier research to acquire sufficient evidence of Wagner operations, recent investigations on Wagner combat prolific disinformation from Prigozhin-linked sources and media outlets.

More recently, in the last quarter of 2022, the Wagner Group shifted towards a more public profile, widespread recruitment, and another marked increase in violent engagement. In the first quarter of 2023, violent events involving the Wagner Group rose in all major areas of conflict, namely Mali, CAR, and Ukraine, from the average number of quarterly events over the previous year. While fighting continued in Mali against Islamist groups in the second quarter of 2023, violent events declined in CAR and Ukraine following a successful campaign with military forces against rebel groups in the former and the eventual capture of the eastern town of Bakhmut in the latter.

Little is known about Wagner Group’s presence in Ukraine prior to the full-sacle Russian invasion. In May 2018, Ukraine’s security service reported to have identified a Wagner trainer of the Karpaty tactical group allegedly comprising Ukrainian hires tasked with reconnaissance and subversive activity. In October of that year, Wagner recruitment offices were allegedly set up in rebel-held Luhansk city, pointing to a probable foothold in the areas held by Russian-backed insurgents in the Luhansk region prior to the overt all-out invasion in February 2022.36Sergey Sukhankin, ‘Unleashing the PMCs and Irregulars in Ukraine: Crimea and Donbas,’ Jamestown Foundation, 3 September 2019 The occupied Luhansk region may have also hosted Wagner bases, given that Ukrainian strikes targeted concentrations of Wagner fighters there on at least three occasions in summer and winter 2022, as well as considering allegations of the Wagner Group running a prisoner-of-war camp in Kadiivka (formerly Stakhanov).37Georgy Aleksandrov, ‘An Exchange to Recruit ‘Classes,’ Novaya Gazeta Europe, 27 April 2023

In addition, in late July 2020, 33 Wagner fighters were detained in Belarus. Initially suspected by the Belarusian authorities of plotting to destabilize the country ahead of presidential elections the following month, the group turned out to be part of an abortive Ukrainian attempt to lure fighters into Ukraine with a false promise of employment in a Latin American country. All were subsequently repatriated to Russia. Sixteen of them are believed to have participated in clashes with the Ukrainian military in Donbas since 2014.38Petr and Mazepa, ‘Wagner PMC in Belarus: 16 of 33 Fighters Have Been Long on the Myrotvorets List,’ 29 July 2023

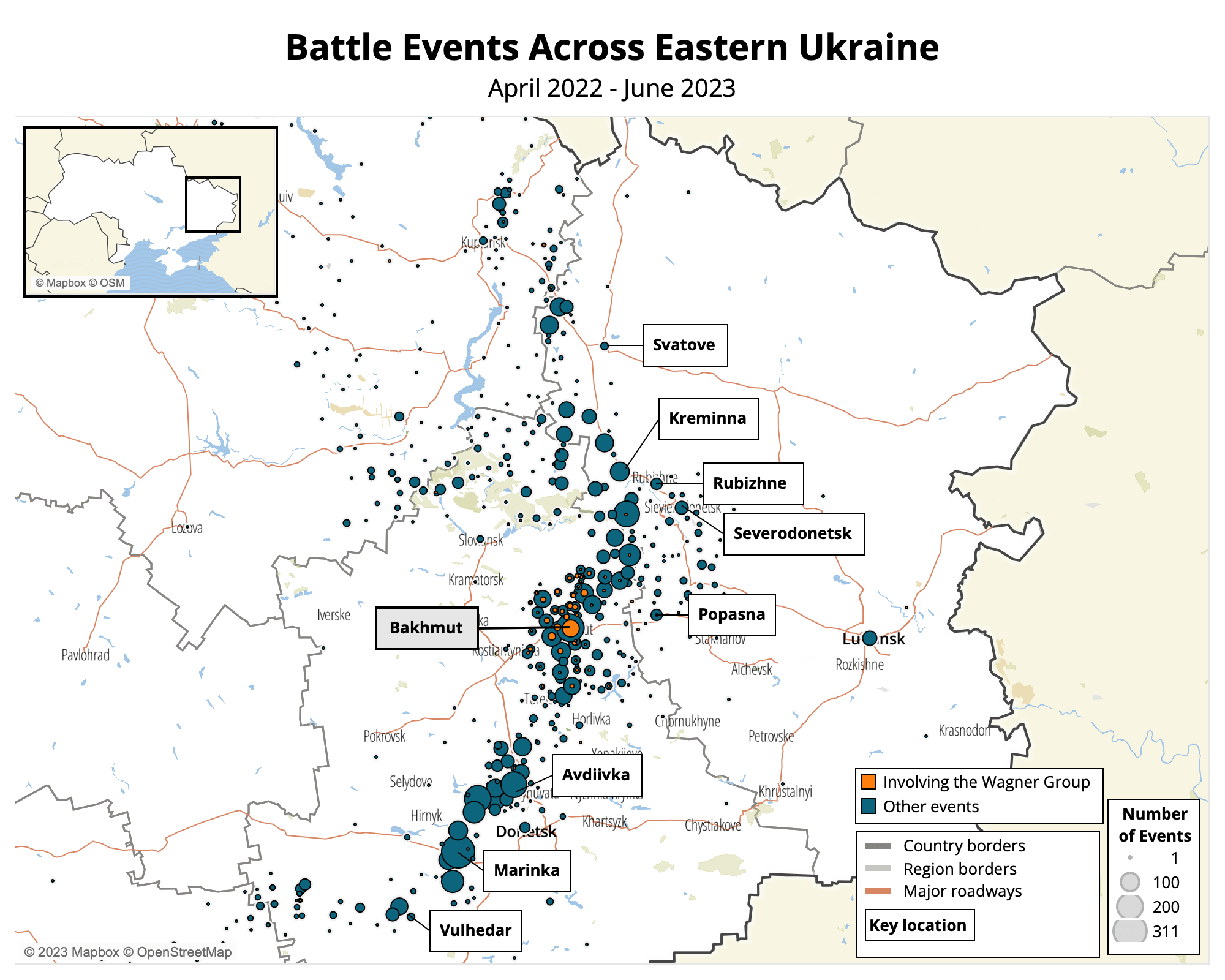

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Wagner Group has participated in military operations alongside Russian military forces. In early April 2022, Wagner mercenaries took part in the battle for Popasna, a Ukrainian stronghold town in the Luhansk region on the former line of contact with rebel-held areas further east. Its fall to invading Russian forces on 8 May enabled the seizure of almost the entire Luhansk region by July – a breakthrough for Russia after it failed to secure Kyiv and subsequent retreat from northern Ukraine in late March. The win in Popasna, however, was attributed to regular Russian forces rather than the Wagner Group, as were the capture of Rubizhne on 12 May and Severodonetsk on 24 June after a long siege.

The group’s presence in Ukraine became more prominent in the last half of 2022, especially during the last quarter. Increased Wagner activity came against the backdrop of setbacks for regular Russian forces, who were first routed in the Kharkiv region and forced to retreat from the right bank of the Dnipro river in autumn, and then failed to gain ground during their attempted offensive in winter, especially near Vuhledar in the southwestern part of the Donetsk region.39Michael Kofman and Rob Lee, ‘Beyond Ukraine’s Offensive,’ Foreign Affairs, 10 May 2023

In all the conflicts they took part in, Wagner mercenaries have been implicated in acts of violence against civilians. The Russian invasion of Ukraine proved that the same is true of regular Russian units whose treatment of civilians in the occupied areas or caught up in fighting is the subject matter of war crime investigations.40International Criminal Court, ‘Situation in Ukraine’, accessed on 23 May 2023 Yet, as relatively few events could be attributed to the Wagner Group, only a few instances of civilian targeting have been recorded. These include an explosion at the prisoner-of-war camp in occupied Olenivka in the Donetsk region on 29 July 2022, in which over 50 detainees perished. Neither Ukrainian allegations of the Wagner Group deliberately blowing up the facility in connivance with other Russian units nor Russian counterclaim of a Ukrainian long-range missile strike targeting their own could be independently verified, as Russia blocked the deployment of UN monitors to the site.41Michelle Nichols and Kanishka Singh, ‘U.N. Chief Disbands Fact-finding Mission into Ukraine Prison Attack,’ 5 January 2023 Other instances concern the forcible displacement of remaining civilians in and around Bakhmut, as well as the detention and eventual abduction of about 100 Russian out-of-combat conscripts in Kadiivka in the Luhansk region. The conscripts allegedly refused to sign contracts with the Wagner Group.42Karolina Hird et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 16 April 2023 In mid-April 2023, two alleged former prisoners and Wagner fighters detailed atrocities committed against civilians and combatants in Bakhmut; one of them was subsequently detained in Russia.43Meduza, ‘Human Rights Activist Releases Testimony from Two Wagner Group Mercenaries Who Describe Executing Ukrainian Civilians, Young and Old,’ 17 April 2023; Grace Mappes, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 24 April 2023 There has been no independent corroboration of the claims to date.

Elsewhere in Ukraine, the Wagner Group appears to be less prominent. Open sources spotted Wagner fighters in the occupied part of the Zaporizhia region and especially in the town of Melitopol in February and April 2023, possibly en route to Bakhmut.44Kateryna Stepanenko, ‘The Kremlin’s Pyrrhic Victory in Bakhmut: A Retrospective on the Battle for Bakhmut,’ Institute for the Study of War, 24 May 2023 There were also reports of Wagner deployments to the occupied part of the Kherson region in April.45Grace Mappes, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 24 April 2023 Both regions are believed to be the likely targets of the ongoing Ukrainian counteroffensive.46Meduza, ‘The shape of things to come The imminent Ukrainian counteroffensive in four scenarios (and four maps) from Meduza’s military analysts,’ 18 May 2023

Wagner has concentrated its efforts on a 50 kilometer section of the 1,000 km frontline in the Donetsk region close to the administrative boundary with the neighboring Luhansk region between occupied Horlivka and recently liberated Lyman, with most persistent fighting in the area of Bakhmut. Invading Russian forces, with Wagner fighters among them, reached the town’s environs in May 2022 and had struggled to seize it until recently.

Bakhmut is a Ukrainian stronghold in the northeastern part of the Donetsk region – practically on the same longitude as Popasna. It is at a crossroads to much bigger and strategically more important Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, which Russia needs to capture to complete its stated takeover of the Donbas. Both were briefly occupied in 2014 by Russian and Russian-backed insurgents led by Igor Girkin (also known as Strelkov),47BBC, ‘Ukraine Crisis: Rebels Abandon Sloviansk Stronghold,’ 5 July 2014 but have since remained in the Ukrainian fold.

Territorial gains attributable to the Wagner Group include less than two dozen small settlements north and south of Bakhmut and mostly occurred between September 2022 and February 2023. The most important of these was the town of Soledar to the north of Bakhmut, which fell on 12 January 2023. Russia’s MoD only obliquely mentioned “assault detachments” in its announcement about the capture of the town; in its reading, their success owed to the prowess of airborne units and aerial bombardments.48Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, ‘Update of the Russian Defense Ministry on the Conduct of the Special Military Operation on the Territory of Ukraine,’ 13 January 2023

Ukrainian forces clung onto Bakhmut against all odds throughout spring. By mid-May, they reportedly controlled only its western outskirts. Denying Wagner victory by 9 May, the day Russia celebrates Soviet Union and allies’ win in the Second World War, Ukrainian forces even managed to secure marginal gains, especially around the critical supply route to Chasiv Yar.49Pjotr Sauer, ‘Russian troops fall back to ‘defensive positions’ near Bakhmut,’ Guardian, 12 May 2023 Heavily attrited Wagner fighters, supported by regular Russian forces, eventually eased out Ukrainian units from the largely obliterated town around 20 May after a nearly year-long siege.50Kateryna Stepanenko, ‘The Kremlin’s Pyrrhic Victory in Bakhmut: A Retrospective on the Battle for Bakhmut,’ Institute for the Study of War, 24 May 2023 Russian President Putin congratulated both in a rare public acknowledgment of the Wagner Group, whose mention preceded that of the Russian forces at large – a sign of high-level benevolence in the Russian political system.51Kremlin.ru, ‘Vladimir Putin Congratulates Russian Military with the Liberation of Artemovsk,’ 21 May 2023 The group’s leader, Prigozhin, subsequently announced that surviving Wagner fighters would withdraw from Bakhmut and Ukraine for several months to rest and reconstitute.

The Ukrainian rationale for holding Bakhmut and Russia’s – or rather Wagner’s – fixation on capturing the embattled town are equally elusive. One of the possible explanations for both sides could be an attempt to pin each other in a pitched battle to drain personnel and materiel elsewhere in the long frontline. For Ukraine, Bakhmut has also become a symbol of Ukrainian resistance to the invasion. For Wagner, the battle for Bakhmut could have been a matter of honor rather than reason amid its open rivalry with regular Russian units. The feud deteriorated during the battle for Bakhmut to the level of expletive-laden diatribes against Russia’s Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of General Staff Valery Gerasimov, with Prigozhin threatening to leave the frontline amid alleged shortages of ammunition in early May.52Brad Lendon et al., ‘Wagner chief says his forces are dying as Russia’s military leaders ‘sit like fat cats,’ CNN, 5 May 2023

Tense relations between the Wagner Group and Russia’s MoD precede the all-out war in Ukraine and may date back to the group’s involvement in the war in Syria in 2018.53Meduza, ‘A Mercenaries’ War,’ 14 July 2022 Command and control remained the bone of contention. Force generation issues since Russian losses in Ukraine in spring and autumn 2022 have led to a proliferation of irregular armed formations leading to competition not only between the Russian MoD and the Wagner Group, but also among the armed formations themselves, e.g. between the Wagner Group and PMCs allegedly set up by the Russian state-owned oil and gas giant Gazprom.54Georgy Aleksandrov, ‘Wagner Betting Against Potok,’ Novaya Gazeta Europe, 28 April 2023; Elizaveta Focht and Ilya Barabanov, ‘Potok near Bakhmut. What is Known about PMCs linked to Gazprom,’ 16 May 2023 While the MoD incorporated most fighting forces in Ukraine, including the hitherto nominally autonomous 1st and 2nd Army Corps of Donetsk and Luhansk ‘People’s Republics,’55Karolina Hird et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 23 April 2023 the Wagner Group acts independently of the regular Russian units despite being provisioned by the MoD with weapons and munitions.56Echo Online, ‘PMC Fad,’ 16 May 2023

The Wagner Group conducted at least two recorded prisoner exchanges with Ukraine independently of Russia’s MoD, an action that corroborates their operational independence.57Karolina Hird et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 16 April 2023; Riley Bailey et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 26 May 2023 In addition, Wagner and other irregular fighters do not enjoy veteran status in Russia.58Kateryna Stepanenko, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 20 April 2023 Rivalry with regular forces has occasionally escalated into internecine fighting. ACLED records several clashes between Wagner fighters and other Russian units: with Chechen Battalion members in Kherson on 17 September 2022; with Russian conscripts reportedly refusing to take on Ukrainian positions near Bilohorivka in the Donetsk region on 19 November 2022 (reportedly leaving 19 dead); and a shootout with regular Russian units in Stanytsia Luhanska in the Luhansk region in mid-April 2023.

Tactical independence from the MoD may, to some extent, explain Wagner’s relative success in Ukraine – although agility and perceived prowess on the battlefield elucidate it only partially.59Meduza, ‘Meduza Details Wagner PMC Tactics in Ukraine,’ 16 March 2023 Wagner’s chief competitive advantage in Ukraine was Russian authorities’ greenlighting of recruitment among Russia’s vast prison population, who Wagner then sent to often suicidal human wave attacks on Ukrainian defense lines. This substantially changes the nature of the Wagner posture in Ukraine compared with Africa, where fighters are arguably better trained and, therefore, less expendable. The inmate recruitment likely started in summer 2022, with Prigozhin – who spent about a decade behind bars himself in the 1980s60Daria Kozlova, ‘The Viceroy of the Grey Zone,’ Novaya Gazeta, 4 April 2023 – touring prisons. Thus, this move ended the persistent denials of any involvement with the Wagner Group and may have generated a 40,000-strong force.61Mitchell Prothero, ‘Wagner Ends Convict Recruitment, Days After Fighters Filmed Beating Officer With Shovel,’ Vice, 10 February 2023 Since early 2023, the MoD appeared to have taken over prison recruitments,62Olga Ivshina et al., ‘Lethal Force: How Russian Defense Ministry Recruits Inmates in Prisons,’ BBC Russian Service, 3 May 2023 possibly deepening the rift in relations.

The Wagner Group, however, continued and even recently intensified its recruiting efforts among the general population.63Daria Talanova, Nikita Kondratyev, ‘Military Ad Campaigns Reach Russian Schools, Metro Stations, and Kindergartens,’ Novaya Gazeta Europe, 19 April 2023 Competition with the MoD is not only about the recruitment of rank-and-file soldiers, however. In late April, the Wagner Group hired Mikhail Mizintsev, the former Deputy Defense Minister responsible for logistics and known as the ‘butcher of Mariupol.’64Telegram Prigozhin’s Press Service, 29 April 2023; Deutsche Welle, ‘Ukraine Updates: Russia Replaces ‘Butcher of Mariupol,’ 30 April 2023 Prigozhin claimed that Mizintsev had been fired from his previous position for providing weapons to the Wagner Group65Karolina Hird et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 5 May 2023 and even suggested that the general replace Sergei Shoigu as Russia’s Defense Minister.66Meduza, ‘We need to take a page from North Korea’s book,’ 24 May 2023 There have also been claims of Wagner recruitment attempts in the Western Balkan countries but the extent of Wagner outreach there could be exaggerated to serve domestic political ends in the region.67Maxim Samorukov, ‘What’s Behind the Posturing of Russian Mercenaries in the Balkans,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 6 April 2023 In addition, some recruitment in the former Soviet Central Asian states and among Russian residents from Central Asia has been intermittently flagged.68The Moscow Times, ‘Wagner Recruiting Kyrgyz, Uzbek Citizens to Fight in Ukraine – Reports,’ 20 July 2022; Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty Siberia. Realities, ‘The Next of Kin of a Kazakh Student in Russia Claim He Has Been Forcibly Recruited by Wagner,’ 20 April 2023

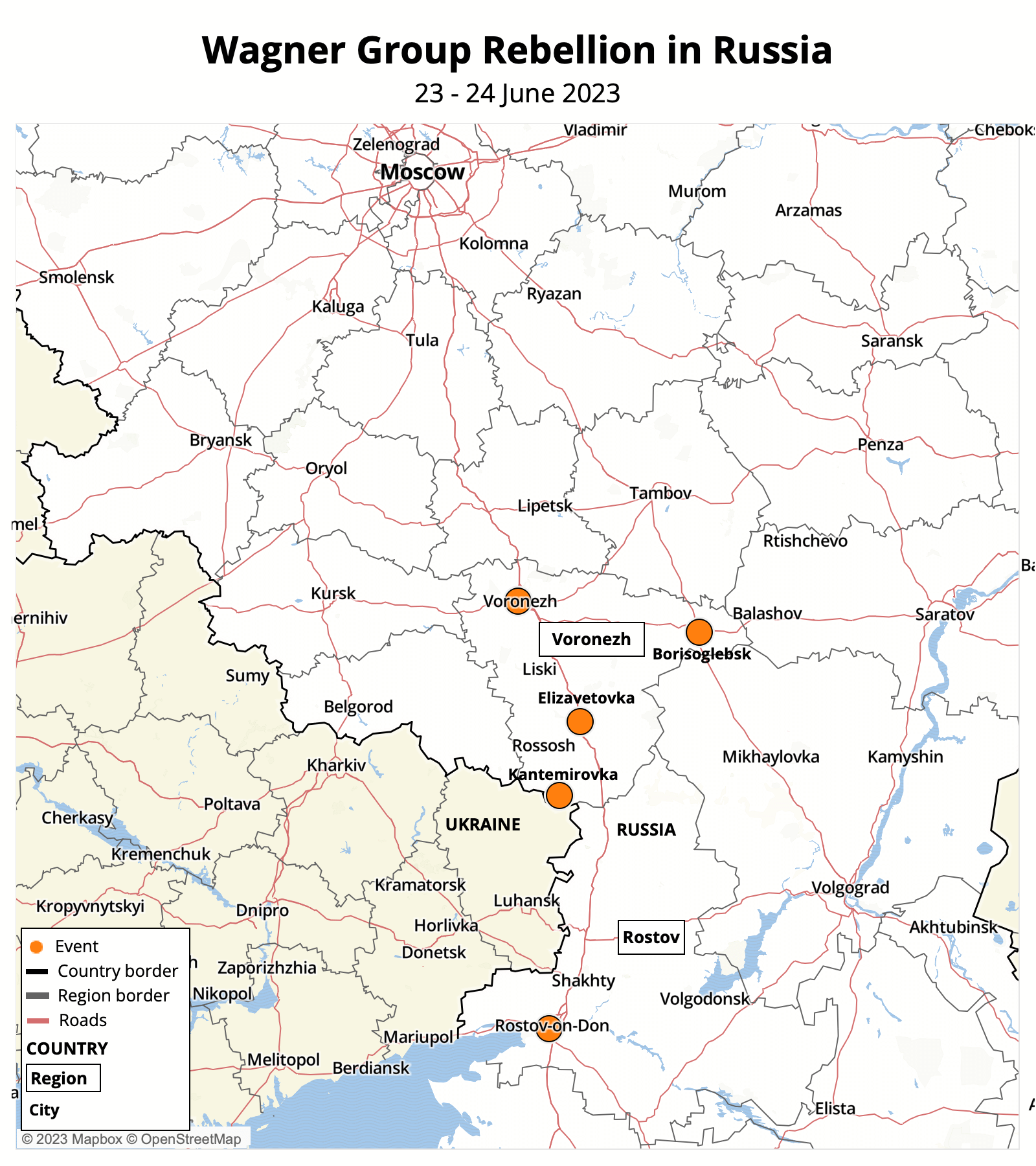

Yevgeny Prigozhin’s long-simmering conflict with the leadership of the Russian MoD came to a head on 23 and 24 June, prompted by the MoD’s order earlier that month that all “volunteer” armed formations conclude contracts with the ministry by 1 July 2023.69Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, ‘Deputy Minister of Defense of Russia Holds a Teleconference on Staffing Russian Armed Forces with Contracted Military Personnel,’ 10 June 2023 On the morning of 23 June, Prigozhin released a manifesto interview questioning the rationale behind the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 and blaming the MoD’s leadership for multiple failures in the conduct of war.70Meduza, ‘Time is running out’ In a new video, Yevgeny Prigozhin directly disputes Russia’s main argument for its war against Ukraine,’ 23 June 2023 On the evening of that day, Prigozhin claimed that Russian regular forces targeted a Wagner camp at an unspecified location in Ukraine with artillery and airstrikes. However, the strikes may have been staged.71Aric Toler, ‘Site of Alleged Wagner Camp Attack Recently Visited by War Blogger,’ Bellingcat, 23 June 2023 Prigozhin further announced that about 25,000 Wagner fighters would commence a “march for justice” toward the Russian capital Moscow to hold Shoigu and Gerasimov to account (see map below).72Andrew Osborn and Kevin Liffey, ‘Russia accuses mercenary chief of armed mutiny after he vows to punish top brass,’ Reuters, 24 June 2023 The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) promptly announced it was investigating Prigozhin for calls to armed rebellion.73Kommersant, ‘FSB opens criminal investigation into armed rebellion after Prigozhin’s remarks,’ 23 June 2023 Overnight, senior Russian military leadership, including erstwhile ally Sergey Surovikin, publicly called on Prigozhin and his fighters to give up on their plans.74Reuters, ‘Russian commander urges Wagner fighters to ‘obey will of president’ and return to bases,’ 24 June 2023

In the early hours of 24 June, the Wagner Group appeared to have seized without a fight the Southern Military District headquarters as well as military and law enforcement sites in Rostov-on-Don after having crossed into the Rostov region from Ukraine’s occupied Donbas.75Ministry of Defence of the United Kingdom, ‘Intelligence Update on Ukraine,’ 24 June 2023 At the time of writing, it is not yet clear whether Russian regular troops had been under orders not to resist Wagner fighters or chose not to. Prigozhin also released a video of himself conversing with Russian Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-bek Yevkurov and Deputy Chief of the General Staff Vladimir Alexeyev, claiming that his fighters had shot down Russian military aircraft targeting both his fighters and civilians during Wagner’s overnight drive toward Rostov-on-Don and reiterating his demand that Shoigu and Gerasimov be handed over to him.76Meduza, ‘‘We’re saving Russia,’ 24 June 2023

Meanwhile, other Wagner units equipped with tanks, armored combat vehicles, artillery, and missile systems continued moving north toward Moscow via the neighboring Voronezh region, where it again encountered Russian airstrikes after having secured military sites in and near Voronezh city.77Riley Bailey, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 25, 2023,’ Institute for the Study of War, 25 June 2023 Overall, since the beginning of its incursion into Russia, it may have downed a total of six military helicopters and a command and control bomber jet,78Oryx, ‘Chef’s Special – Documenting Equipment Losses During the 2023 Wagner Group Mutiny, 24 June 2023 reportedly killing 13 personnel onboard. A projectile fired by a Russian military chopper or a Wagner surface-to-air missile launcher aiming at it hit a kerosene tanker in Voronezh city, prompting a massive fire. Losses incurred by the Wagner Group throughout the campaign have not been disclosed at the time of writing.

In his morning address to the nation, President Putin accused the rebels of treason – without naming them – claimed the army’s wholesale support, and vowed to put down the rebellion.79Vladimir Putin, ‘Address to Citizens of Russia,’ 24 June 2023 His loyalists scrambled to reassert their allegiance, including the leader of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov, who redeployed his special forces battalion from Marinka near the occupied Ukrainian city of Donetsk to Russia’s Rostov region. Russian authorities blocked major highways leading to Moscow and announced a counter-terrorist operation.80RBC, ‘Regions where anti-terrorist operation is underway and roadblocks. Map,’ 24 June 2023

In the afternoon, two explosions and several instances of small-arms fire occurred in the area of the Southern Military District headquarters in Rostov-on-Don. There were also reports of verbal altercations between Wagner fighters and passers-by, albeit the overall atmosphere in the city appeared calm and was reminiscent of the Russian bloodless occupation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in 2014.81Andrew Roth, ‘I hope he wins’: how tense Rostov-on-Don welcomed Prigozhin’s forces,‘ Guardian, 24 June 2023

In the evening, Russian air forces blew up a bridge near the Voronezh region’s town of Borisoglebsk. Three civilians, including a child, were injured while crossing the bridge in a car. When Wagner columns had reached the Lipetsk region less than 200 km south of Moscow and Kadyrov’s battalion was still due to reach Rostov-on-Don, Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko claimed to have negotiated a settlement with Prigozhin, with the latter agreeing to return his columns to Wagner camps in exchange for amnesty. Belarus apparently offered Prigozhin a safe haven.82Gabriel Gavin and Christian Oliver, ‘Kremlin says Prigozhin will depart for Belarus after rebellion fizzles,’ Politico, 24 June 2023 Subsequently released footage showed Prigozhin and his fighters leaving Rostov-on-Don, cheered by crowds.83Pjotr Sauer, ‘Prigozhin’s rockstar exit from Rostov shows public support for ‘traitor,’ Guardian, 25 June 2023

The rebellion, albeit short-lived, became the first armed challenge to the central Russian authority since the abortive putsch in Moscow in 1993 and the two wars in Chechnya in the mid-1990s and early 2000s. Questions remain on the impact of the mutiny on Russia’s ability to pursue its aggression against Ukraine and to control developments within its own borders, as well as on the future of the Wagner Group as a standalone actor in Ukraine and in other conflicts, especially in Africa. In his address on 26 June, President Putin offered Wagner fighters a choice of either entering into contracts with the MoD, quitting the force altogether, or redeploying to Belarus.84Vladimir Putin, ‘Address to Citizens of Russia,’ Kremlin.ru, 26 June 2023

In late 2017, reports emerged of security and mining contracts signed between the CAR government and a Russian company called Lobaye Invest SARLU, allegedly linked to the Russian PMC Sewa Security Group.85Cole Spiller, Celia Metzger, and Matthew Crittenden, ‘Russian Engagement in Africa: Case Study – Mining And Private Security Companies in the Central African Republic,’ Scope, 19 March 2021; The Sentry, ‘Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,’ June 2023 While reports of direct Russian support in CAR and links with the Wagner Group were initially unclear, Russian PMC engagement in CAR took on a more public profile after the signing of bilateral agreements in 2018 between the Russian and CAR governments, officially exchanging military support and weapons for mining concessions.86Dionne Searcey, ‘Gems, Warlords and Mercenaries: Russia’s Playbook in Central African Republic,’ New York Times, 30 September 2019 By January 2018, Russia delivered both weapons, five military instructors, and 170 civilian instructors.87The Sentry, ‘Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,’ June 2023, p. 7 Russia’s initial involvement and limited direct engagement shifted over time to the current public image campaign, including Russian military statues in the capital city Bangui, funding for local radio stations, Russian mercenary deployment, and a former Russian GRU official, Valery Zakharov, working as the president’s national security adviser. Recent reports have even questioned the agency of the CAR government, calling it a “zombie” host to Russian interests.88Anthony Loyd, ‘Diamond-rich African country is a zombie host for Wagner Group,’ The Times, 19 May 2023

Amidst a rebel group offensive prior to the December 2020 elections, the Wagner Group’s direct engagement in conflict escalated as the mercenaries fought alongside CAR military forces (FACA) and other allied troops. The FACA had already been supported by United Nations peacekeepers (MINUSCA) and additional Rwandan troops when Wagner intervened militarily in CAR.89Rwanda Ministry of Defense, ‘Rwanda Deploys Force Protection Troops To Central African Republic,’ 20 December 2020 Wagner initially focused on confronting a coalition of rebel militias led by former President François Bozizé operating under the name of the CPC. The CPC launched an offensive in late 2020 across CAR to overthrow the government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. Despite the territorial gains by the CPC in 2020 and early 2021, the FACA and allied forces – including the Wagner Group – regained much of the area that had fallen under CPC control by May 2021.

In subsequent months, Wagner mercenaries carried out sustained violence against civilians – especially ethnic Fulani people and Muslims – until November 2021, well after the CPC counter-offensive and despite tapering battles against the CPC (for more on the initial CPC offensive, see ACLED’s previous report on Wagner’s operations in Africa). As several prominent CPC-affiliated militias had recruited soldiers among the ethnic Fulani people, also predominantly Muslim,90Irene Mia, ‘The Armed Conflict Survey 2022,’ The International Institute for Strategic Studies, November 2022 Wagner often targeted Fulani communities and other suspected collaborators.91Florence Morice and Charlotte Cosset, ‘In the Central African Republic, victims of Russian abuses break the law of silence,’ Radio France Internationale, 5 March 2021 Although Wagner initially fought alongside MINUSCA and Rwandan troops, both groups ceased joint operations with Wagner after noting numerous human rights abuses carried out by the mercenaries.92Corbeau News, ‘RCA : les troupes rwandaises cessent leur opération conjointe avec les mercenaires de Wagner,’ 13 June 2021; UN Info, ‘RCA : des experts inquiets de l’utilisation par le gouvernement de « formateurs russes » et de contacts étroits avec les Casques bleus,’ 31 March 2021

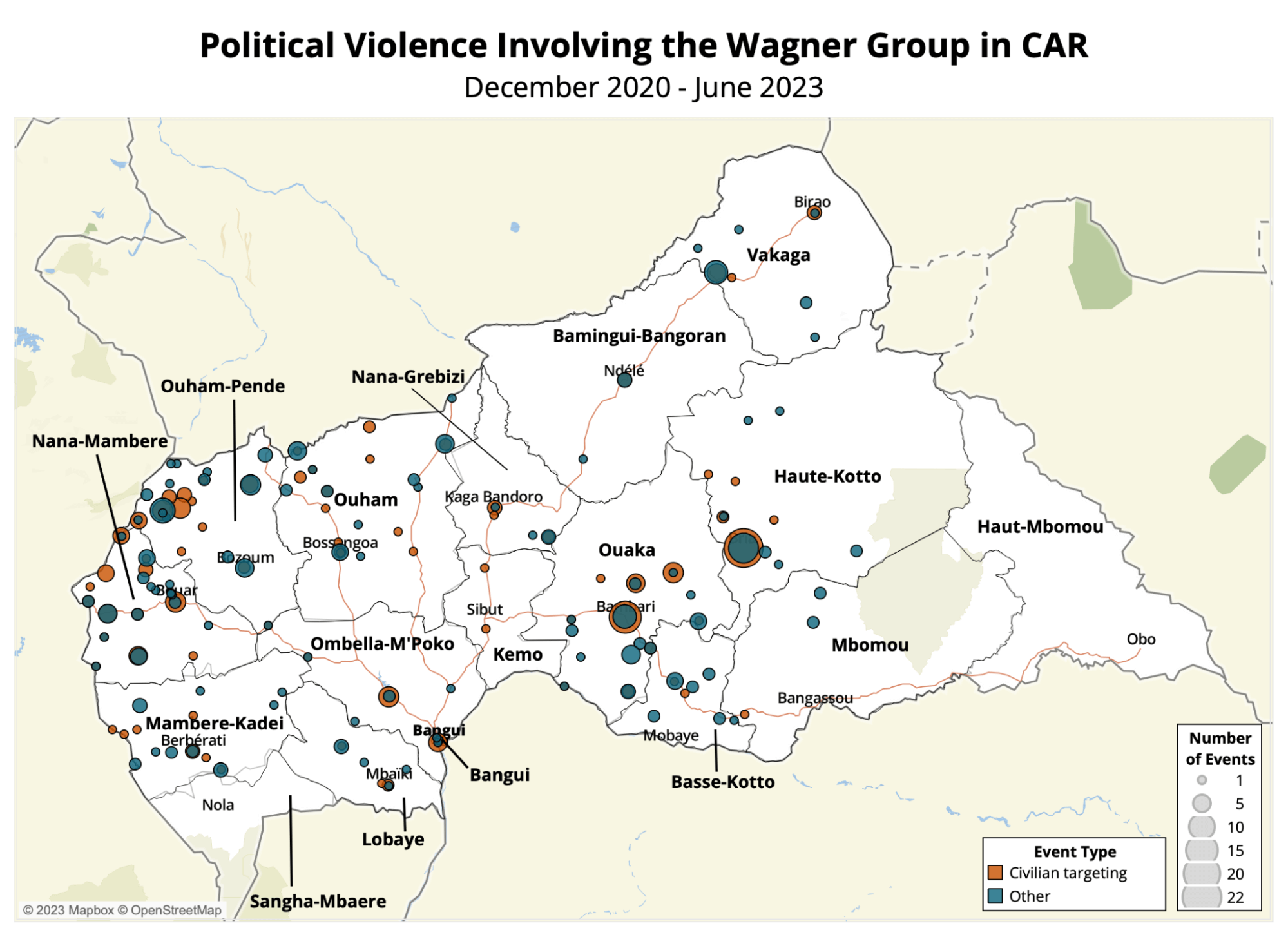

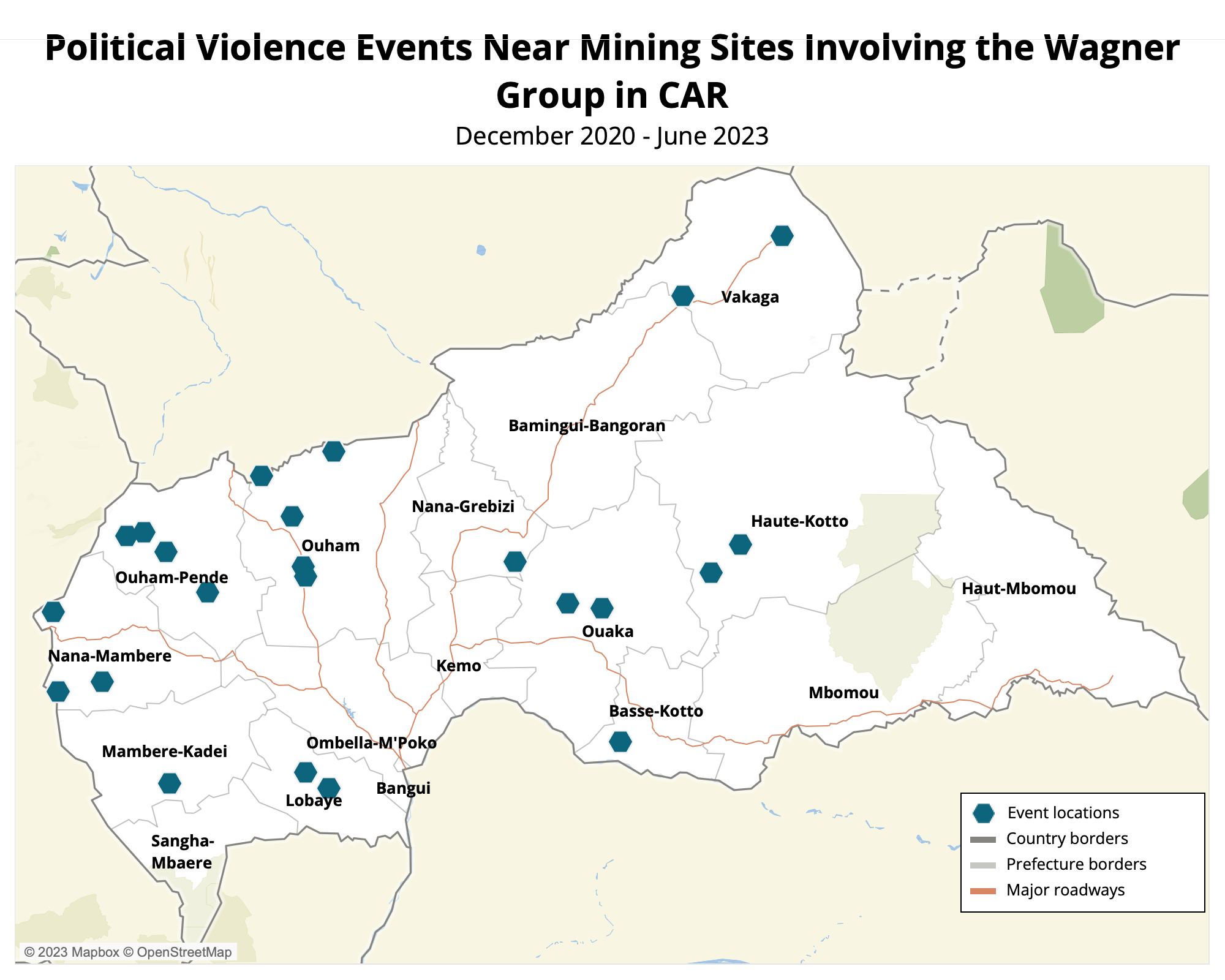

After engaging in the CPC counter-offensive in December 2020, Wagner became one of the dominant agents of political violence in CAR, with troop estimates reaching 2,600 fighters.93The Sentry, ‘Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,’ June 2023, p. 9 Between December 2020 and May 2023, 37% of all political violence in CAR involved the Wagner Group. During this time, Wagner forces engaged in political violence in all prefectures in CAR except Haut-Mbomou and Sangha-Mbaere (see map below).

From November 2021 to September 2022, rebel activity declined in CAR, suggesting the counter-offensive by FACA and allied forces made progress in suppressing the CPC. As a result, armed operations conducted by the Wagner Group also declined between 2021 and 2022. Some reports, however, note that Wagner leadership redeployed some of their mercenaries from CAR to Ukraine in March 2022 to join Russian military forces.94Bisong Etahoben, ‘Russian Mercenaries Leaving Central African Republic After Ukraine Invasion,’ HumAngle, 21 March 2022

However, the trend towards diminishing political violence changed with an armed escalation attributed to CPC-aligned rebel groups in November 2022. Several armed groups mobilized again following the killing of Zakaria Damane, a leader in the rebel Patriotic Rally for the Renewal of the Central African Republic (RPRC), at the hands of Wagner in Ouadda, Haute-Kotto prefecture in February 2022.95UΝ Security Council, ‘Midterm report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2648,’ S/2023/87, 10 February 2023 These groups had been part of disarmament and demobilization under the leadership of Damane, but following his death, reorganized under the CPC coalition in July 2022.96UΝ Security Council, ‘Midterm report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2648,’ S/2023/87, 10 February 2023

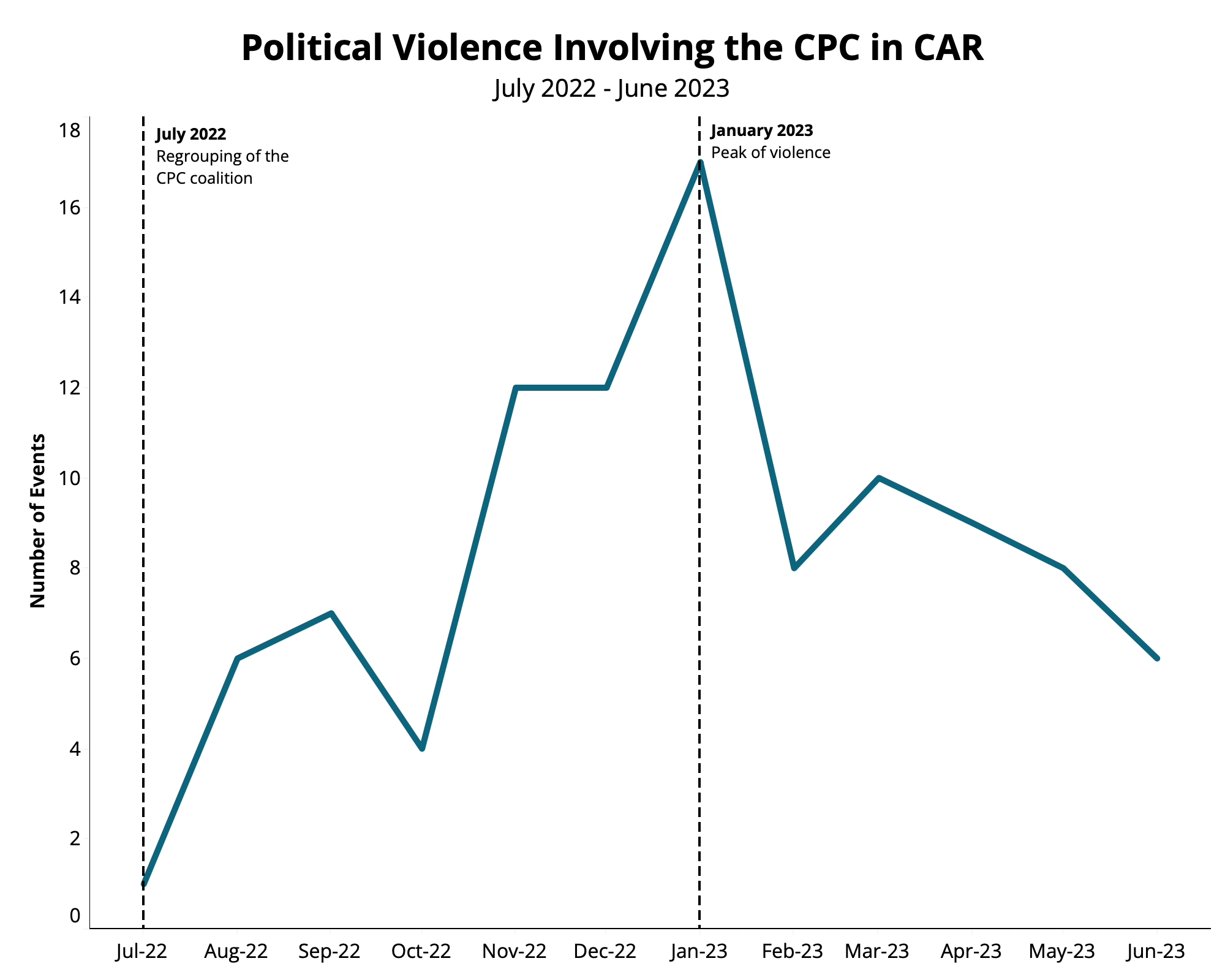

After the regrouping of the CPC coalition, the rebel offensive resulted in widespread violence in numerous prefectures across the country. Violence peaked in January 2023 (see graph below), with rebel groups attacking critical government infrastructure, including a strategic customs post in Beloko, Nana-Mambere prefecture. The post lies on a trade route with Cameroon that provides the government’s main source of income from customs tariffs.97Enrica Picco, ‘Ten Years After the Coup, Is the Central African Republic Facing Another Major Crisis?’ International Crisis Group, 22 March 2023 Wagner and MINUSCA peacekeepers have also joined FACA in a counter-offensive to push back the CPC but at lower levels than during the peak in January. Further, there are no reports of Wagner mercenaries and MINUSCA peacekeepers fighting together against the CPC in the recent counter-offensive, as was the case in early 2021.

Along with the overall reduction in political violence in CAR, civilian targeting perpetrated by the Wagner Group also declined in 2022 and continues to remain at relatively low levels in 2023. However, Wagner’s indiscriminate use of explosives gained further attention after mercenaries were caught throwing Molotov cocktails into the French-owned Castel brewery in March 2023.98Africa News, ‘CAR: Is beer at the heart of France, Russia’s battle for influence?’ 16 March 2023 A frequent use of explosive violence coincided with the Wagner counter-offensive against the CPC in 2020-21, often resulting in civilian casualties. Since December 2020, Wagner has engaged in explosive violence more than any other actor in CAR, using helicopters to drop explosives against a wide range of targets, including CPC bases, mining sites, and civilian settlements. In response to the late 2022-23 offensive by CPC militants, there has been a subsequent rise in explosive and remote violence activity. The number of these events in 2023 already surpassed the previous year, with civilians frequently falling victim to indiscriminate explosives.

Large-scale desertions of local recruits among the FACA and the Wagner Group ranks were reported against the backdrop of a growing CPC offensive in 2022. These recruits allegedly began to leave the FACA and Wagner to join the CPC after around 100 fighters went missing and were allegedly deployed to Mali or Ukraine.99Chief Bisong Etahoben, ‘CAR: Mass Desertions Within Ranks Of Ex-Seleka Rebels,’ HumAngle, 11 November 2022 Wagner has recruited and trained local militants in CAR in order to counter rebel groups, often using the Wagner base in Berengo, a town about 60 kilometers from the capital Bangui, to facilitate military training exercises.100The Sentry, ‘Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,’ June 2023, p. 12 In media reports, these militants are often called “proxy” forces or “Black Russians,”101See for example Bertrand Yékoua, ‘Centrafrique : désertion en cascade parmi les Russes noirs à Bambari,’ Corbeau News, 10 November 2022; Chief Bisong Etahoben, ‘CAR: Mass Desertions Within Ranks Of Ex-Seleka Rebels,’ HumAngle, 11 November 2022 posing challenges to discerning between separate armed groups and local recruits fighting within Wagner ranks.102Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central African Republic,’ 28 February 2023

Wagner’s recruitment of fighters and training of other armed groups are often provided to former self-defense militias known as Anti-Balaka, now loyal to President Touadéra. Some recruits also come from ex-Seleka fighters, a rebel coalition against Anti-Balaka whose former leader, Michel Djotodia, became the president of CAR in 2013. Desertions back to the CPC in November 2022 of former ex-Seleka and Anti-Balaka rebels who were fighting with FACA and Wagner illustrate the persisting tensions between these former enemies.

While Anti-Balaka militia violence grew alongside the initial CPC offensive in 2020, this trend was reversed as military forces and allied groups retook territory throughout 2021. Yet, in late 2021, Wagner’s training of Anti-Balaka fighters aligned with President Touadéra coincided with a rise in violent events. The integration of Anti-Balaka fighters within Wagner ranks is evidenced by reports of Wagner paying militants103The Sentry, ‘Architects of Terror: The Wagner Group’s Blueprint for State Capture in the Central African Republic,’ June 2023, p. 36 – 41 and protests led by unpaid fighters outside Wagner bases in Bambari city, Bambari prefecture.104Bertrand Yékoua, ‘À Bambari, les miliciens Anti-Balaka faction Touadera manifestent et réclament leur paiement,’ Corbeau News, 16 February 2022

The training and recruitment of militants by the Wagner Group have exacerbated threats to both the local civilian population and neighboring countries. Since Wagner began recruiting and training the Touadéra-aligned faction of the Anti-Balaka, these militants have primarily targeted civilians rather than fighting against rebel groups.105Of the total number of political violence events recorded by ACLED involving pro-Toudéra anti-Balaka militants, nearly 70% involve civilian targeting, with further looting and destruction of civilian property. The history of sectarian violence, along with the presence of Wagner Group and alleged “Black Russian” mercenaries in resource-rich Vakaga prefecture further heightens the risks to the civilian population.106UN Security Council, ‘Midterm report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2648,’ S/2023/87, 10 February 2023 Across the border, US intelligence reports outline threats to neighboring Chad by militants trained by the Wagner Group in northern CAR, with several cross-border attacks reported in the last year alone, according to ACLED data.107Benoit Faucon, ‘U.S. Intelligence Points to Wagner Plot Against Key Western Ally in Africa,’ Wall Street Journal, 23 February 2023

Control of natural resources undergirded the entrance of the Wagner Group into CAR, with contracts exchanged for control of mines between Wagner-linked companies and the CAR government emerging in late 2017.108Carl Schreck, ‘What Are Russian Military Contractors Doing In The Central African Republic?’ Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 2 August 2018; Anton Baev, Mikhail Maglov, ‘Contract from President: What the Company Linked to Prigozhin Won in the CAR,’ The Bell, 18 August 2018 Prigozhin-linked companies, such as Lobaye Invest, Midas Resources, and Diamville, secured contracts to operate gold and mining sites in CAR, while Russian PMCs provide security services to mines and political leaders.109Dionne Searcey, ‘Gems, Warlords and Mercenaries: Russia’s Playbook in Central African Republic,’ New York Times, 30 September 2019; All Eyes On Wagner, ‘RCA: Les Diamants de Sang de Prigojine,’ December 2022 Beyond gold and diamond mining, evidence also emerged of links between a logging company called Bois Rouge and Wagner.110All Eyes On Wagner, ‘RCA: Les Diamants de Sang de Prigojine,’ December 2022 Wagner strengthened control over the independent diamond mining industry in CAR, and one person involved in the diamond industry explained that “the majority of independent collectors are financed by the Russians…Today, an independent collector cannot work if he does not work with Wagner.”111Interview reported in All Eyes On Wagner, ‘RCA: Les Diamants de Sang de Prigojine,’ December 2022, p. 19

The limited reach of the Touadéra government in rural areas and the 2020 offensive by CPC-aligned militias restricted access to mining sites for companies operating through Bangui. Attacks on miners rose in 2020 and then escalated by nearly three times in 2021 from the previous year. Unsurprisingly, Lobaye – a southwestern region with numerous sites linked to Wagner-linked Lobaye Invest and Bois Rouge112All Eyes On Wagner, ‘RCA: Les Diamants de Sang de Prigojine,’ December 2022, p. 11 – was the initial area Wagner focused on regaining control from CPC militias. Areas where Wagner has concentrated its military operations since December 2020 also coincide with strategic Russian-run mining sites – especially around Bria, where ACLED records the highest number of conflict-related fatalities in 2022.113Chief Bisong Etahoben, ‘CAR: Russian Mercenaries Assert Authority Over Bria, Say UN Forces Not In Charge,’ HumAngle, 19 July 2021 In one event in January 2022, Wagner mercenaries reportedly killed dozens of civilians around gold mines near Bria.114The African Crime and Conflict Journal, ‘Wagner Group accused of killing 70 Civilians in Gold Mine Massacre,’ 31 January 2022 Notable violence involving Wagner is also concentrated around the large Ndassima mining site, where Russian Lobaye Invest has expanded resource extraction.115Erin Banco, ‘U.S. cable: Russian paramilitary group set to get cash infusion from expanded African mine,’ Politico, 19 January 2023

In recent years, Wagner mercenaries clashed with armed groups on several occasions to control strategic mining sites (see map below). Since December 2020, ACLED records 17 battles over mining sites across the country, with Wagner involved in 70% of these events. Battles were highest in Ouham prefecture, followed by Nana-Mambere and Lobaye prefectures. Fighting over mining sites was highest during 2021, typically between CPC-aligned militias against military forces and Wagner. Although not directly targeting civilians, battles at mining sites led to numerous civilian fatalities. On one occasion in late September 2021, Wagner and FACA forces clashed for two days with a militia under the CPC militia at a mining site in Banda-Kolo Yangba, Basse-Kotto prefecture, reportedly leaving 42 fatalities, mostly among civilians.

During the 2022 CPC offensive, concentrated violence took place in Vakaga prefecture, where the Ministry of Mines forbade local miners from operating and gave control to Russian companies in September 2022.116Enrica Picco, ‘Ten Years After the Coup, Is the Central African Republic Facing Another Major Crisis?’ International Crisis Group, 22 March 2023 To counter the proliferation of armed groups and growing violence in Vakaga prefecture, the CAR government agreed to cooperate with the Sudanese paramilitary Rapid Support Forces in December 2022.117Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central African Republic,’ 28 February 2023 Numerous foreign militaries, mercenaries, and rebel groups have operated in the resource-rich Vakaga prefecture in recent years, collaborating for mutual interests and competing for access to mining sites.

Amid these clashes, violence against miners peaked in July 2021 when FACA and the Wagner Group wrestled for control from CPC militias. Miners are frequently targeted in violence as Wagner and other armed groups compete for the control of gold, diamond, and other natural resource sites. ACLED records at least 20 cases of violence targeting miners between December 2020 and June 2023, mostly concentrated in Nana-Mambere, Ouaka, Ouham, and Vakaga. Wagner mercenaries were reported to be responsible for the violence in at least half of these events. Among the most high-profile events was a raid conducted by Wagner on a mine near the Sudanese border, where dozens of local workers were reportedly killed.118Jason Burke and Zeinab Mohammed Salih, ‘Russian mercenaries accused of deadly attacks on mines on Sudan-CAR border,’ The Guardian, 21 June 2022 Attacks continued in the first half of 2023, with violence against miners reported in Brago, Vakaga prefecture, and around Ouham River, Ouham-Pende prefecture. The attack in Brago killed a Sudanese miner and led to eight others arrested, with an additional three gold miners killed near Ouham River.

The Wagner Group has emerged as a significant yet shadowy armed actor in Mali since it began operations in late 2021. The group was tasked with conducting counter-militancy operations and bolstering the security of Mali’s transitional government, which is run by a military junta that assumed control following two coups in August 2020 and May 2021. Wagner’s presence in Mali has not been formally recognized by Malian authorities. Instead, they refer to these forces ambiguously as Russian instructors or allies in communications or backup soldiers (supplétifs), as often reported in the media.

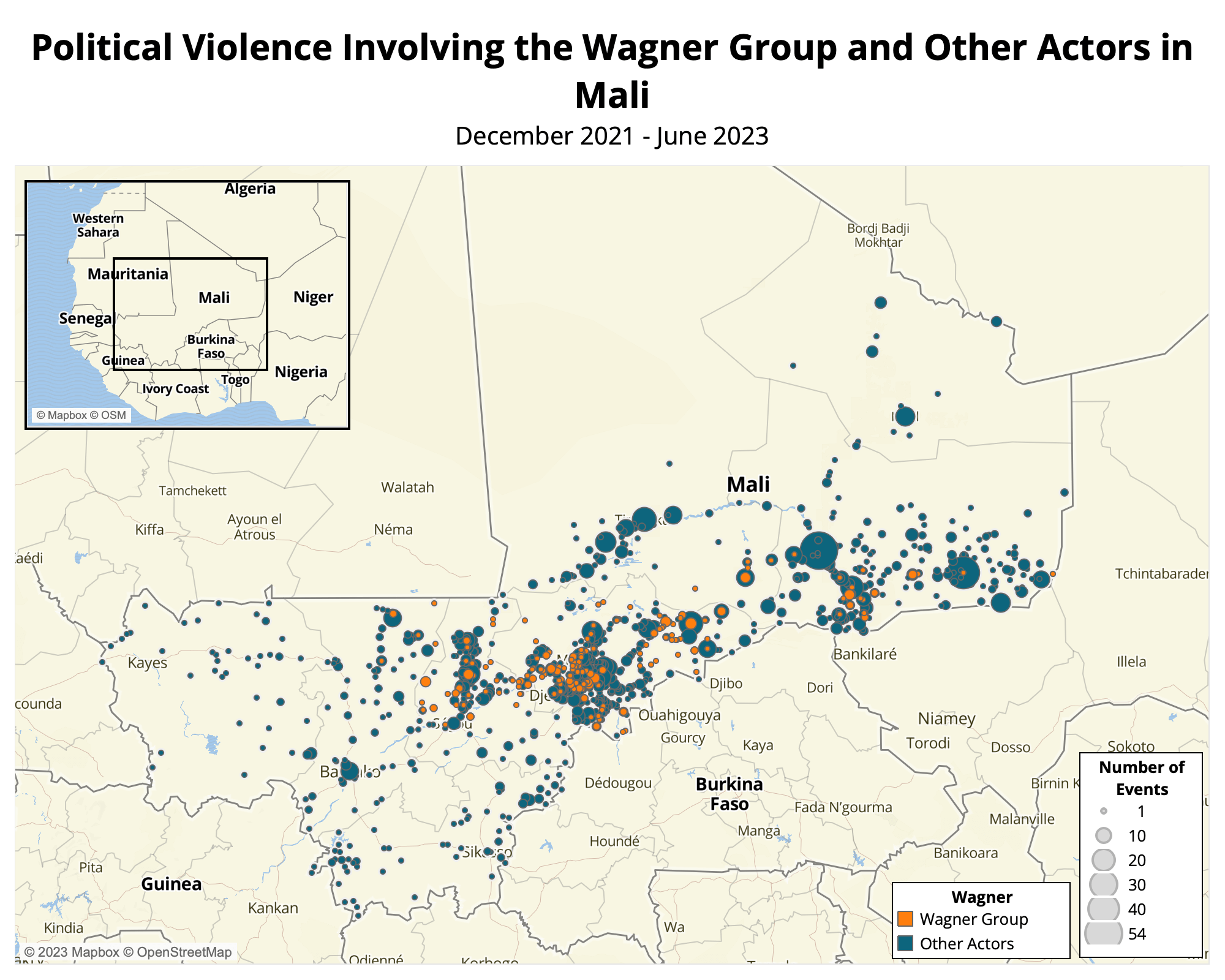

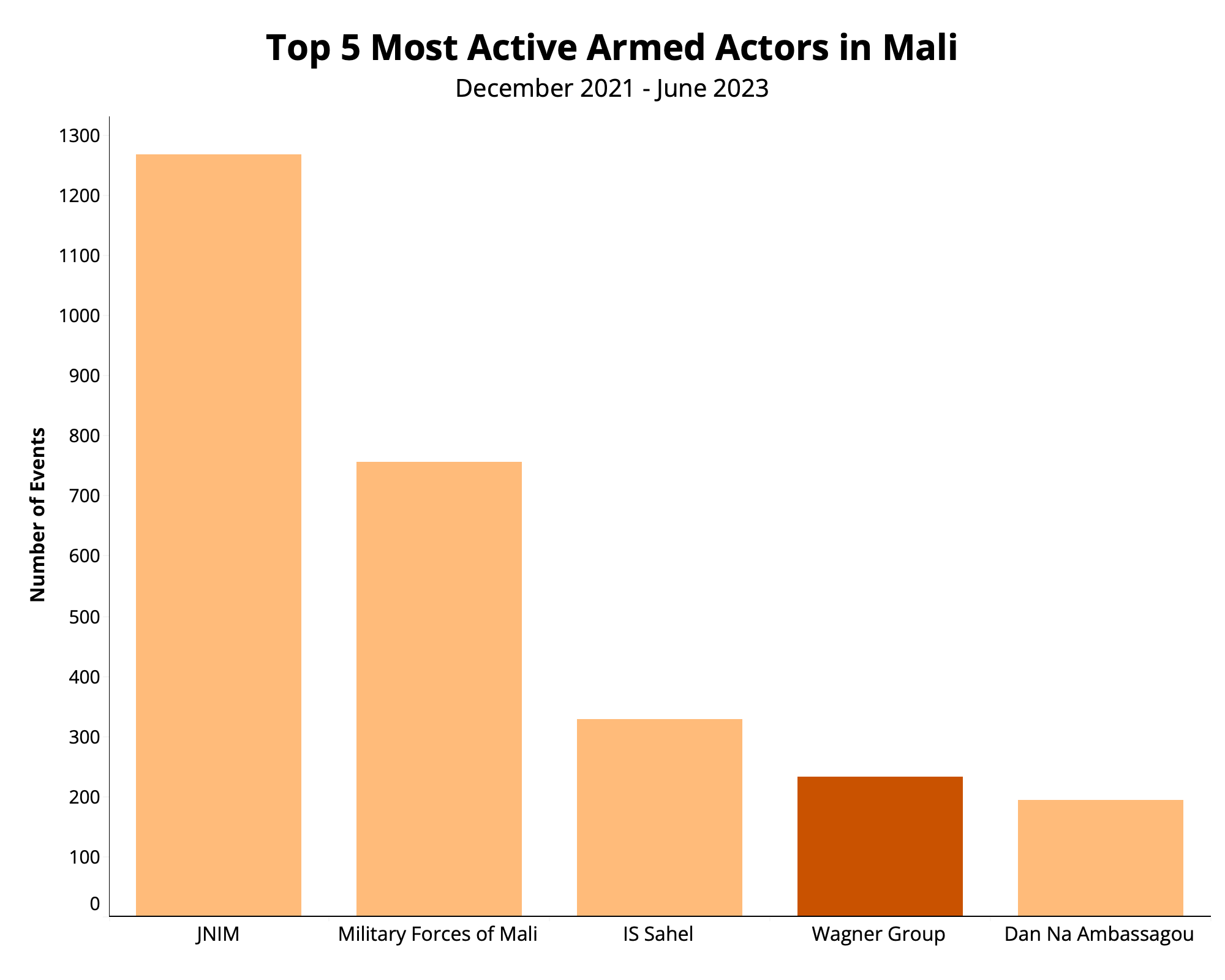

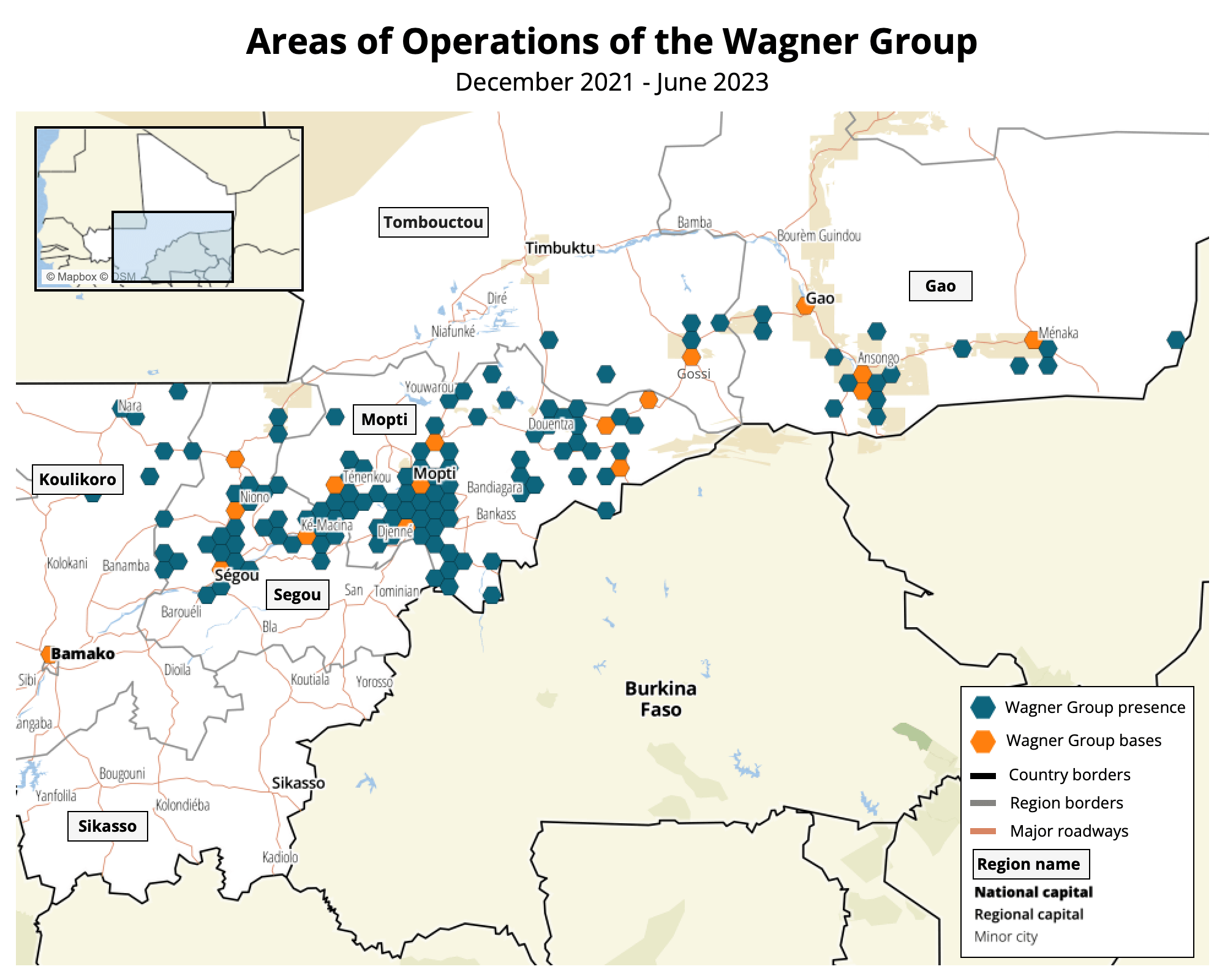

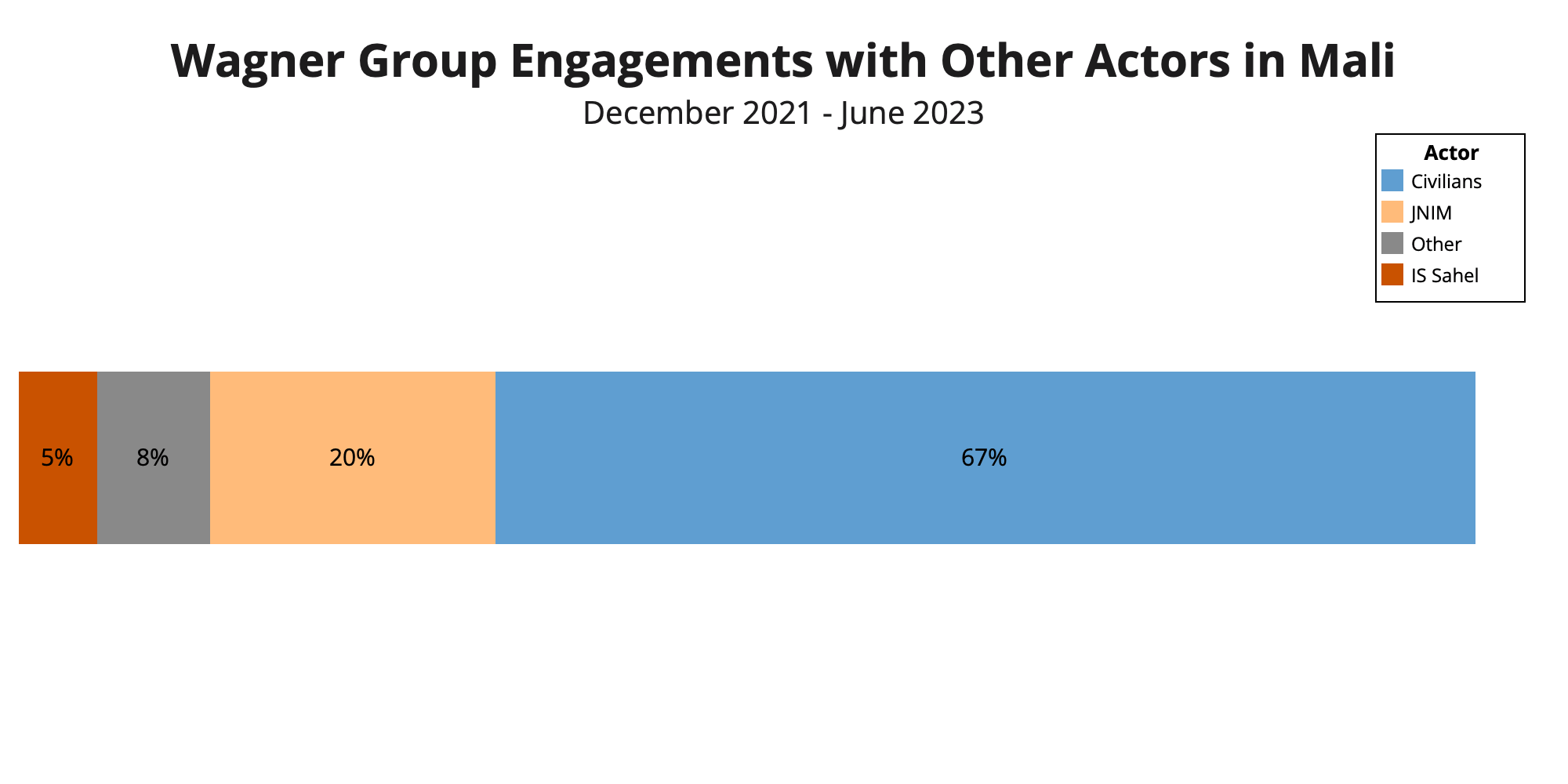

Between 1 December 2021 and 30 June 2023, ACLED records 298 political violence events involving the Wagner Group in Mali, highlighting its independent operations, those in collaboration with the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) and with Dan Na Ambassagou and Dozo (or Donso) militias in Mopti and Segou regions, and more sporadically alongside ethnic-Tuareg pro-government militias in Menaka and Gao regions. According to local insights, the Wagner Group is believed to participate in approximately 90% of FAMa operations in central Mali.119Personal communications with key informant from Mopti, May 2023 However, ACLED maintains a more conservative approach and refrains from presumptively including Wagner in FAMa activities in the absence of substantiated reports. Wagner’s level of engagement currently makes it the fourth most active armed actor in Mali, after the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel), and FAMa (see the map and chart below).

Despite Malian authorities not admitting to the presence of Wagner mercenaries, evidence from various sources has confirmed their activities in the country. Both Russian President Putin and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov have conceded the presence of the group in Mali.120RFI, Vladimir Poutine confirme la présence de mercenaires russes au Mali,’ 8 February 2022 In April 2023, Yevgeny Prigozhin denied casualties among his personnel in a complex suicide attack that targeted FAMa and Wagner positions at Sevare Airport.121VOA Africa, ‘Wagner Boss Says Mercenaries in Mali Unhurt,’ 26 April 2023 Following the attack, Wagner personnel stationed in Sofara retreated to Sevare, leaving only their pilots at the Sofara military camp, which has been a key operational hub for Wagner and a detention site where prisoners were subject to torture during interrogations.122OHCHR, ‘Mandats du Groupe de travail sur la question de l’utilisation des mercenaires comme moyen de violer les droits de l’homme..,’ 30 December 2022

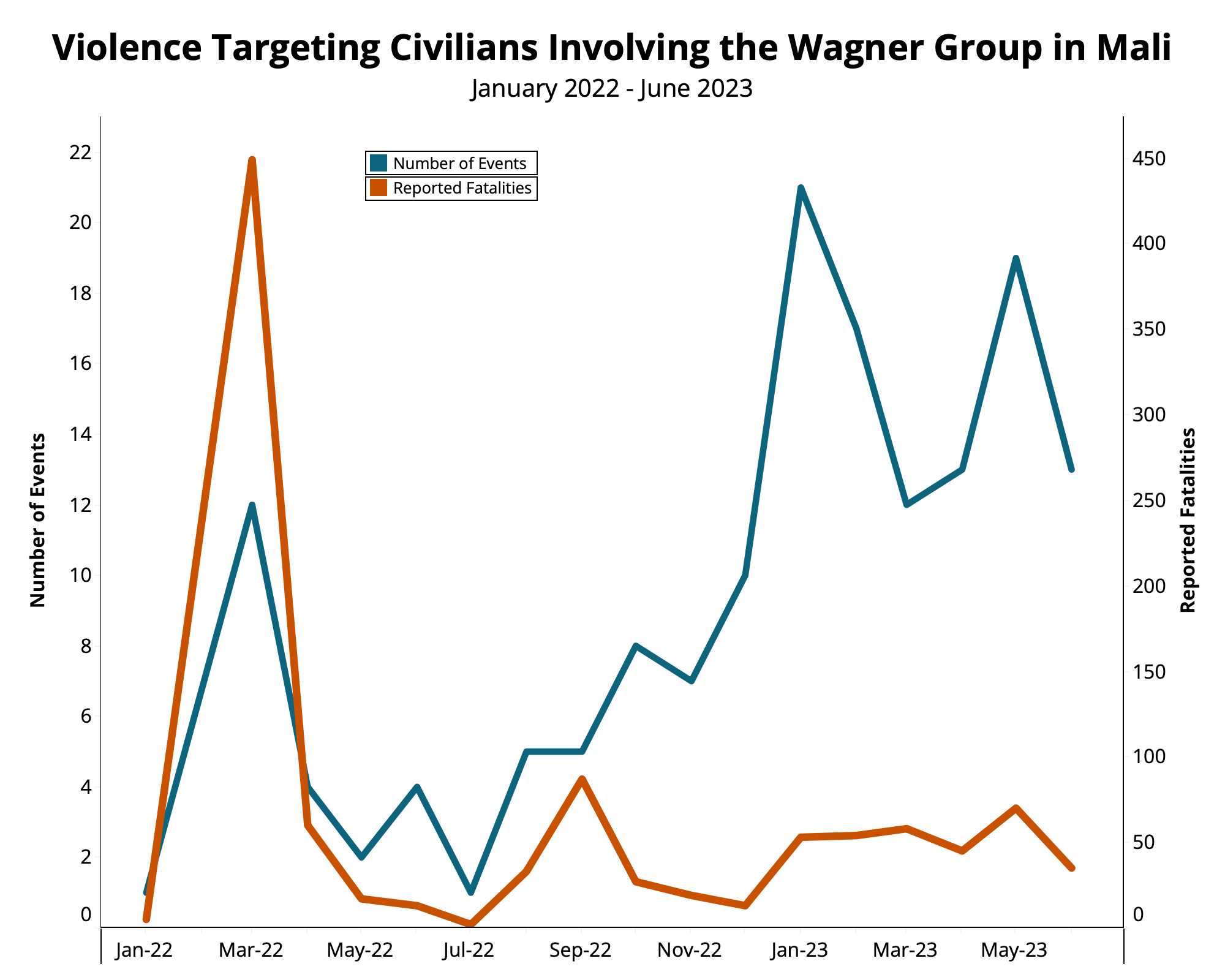

Since the Wagner Group’s arrival in Mali, initial estimates suggested a deployment of around 1,000 personnel, however, the projected numbers have incrementally risen to about 1,200.123John Irish and David Lewis, ‘EXCLUSIVE Deal allowing Russian mercenaries into Mali is close – sources,’ Reuters 13 September 2021; Jared Thompson, Catrina Doxsee, and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., ‘Tracking the Arrival of Russia’s Wagner Group in Mali,’ CSIS, 2 February 2022; Sylvie Corbet and Samuel Petrequin, ‘France and EU to withdraw troops from Mali, remain in region,’ Associated Press, 17 February 2022 A recent article in the New York Times citing leaked US intelligence documents, posited that there were over 1,645 Wagner personnel stationed in Mali.124Michael Schwirtz, ‘Wagner’s Influence Extends Far Beyond Ukraine, Leaked Documents Show,’ New York Times, 8 April 2023 The actual figure remains uncertain, but what is clear is that early speculations of Wagner diverting personnel from Mali to the war in Ukraine were unfounded. This conclusion is not drawn from the reported increase in personnel, but is rather illustrated by the expanding footprint of Wagner in the West African nation and an upsurge in operational intensity since the beginning of 2023. Wagner’s operations peaked in January 2023 and continued at high levels for much of 2023.

An important aspect of Wagner’s deployment in Mali is the alleged monthly fee of US$10 million for its services charged to the transitional government of Mali. Over the course of a year, this sum would amount to twice the annual budget of Mali’s Ministry of Justice. This figure provides a comparative perspective on the size of Wagner’s compensation.125Jean-Michel Bos, ‘Wagner coûte une fortune aux Etats africains,’ Deutsche Welle 18 March 2023

After France’s Operation Barkhane started its military drawdown from Mali, Wagner forces have progressively occupied former French bases located in Timbuktu, Gossi, Menaka, and Gao. In addition to occupying former French bases, ACLED identified 13 other locations where Wagner has established bases (see map below). The transfer of the military camp in Gossi in April 2022 turned into a significant episode of information warfare. French forces, using drone surveillance, countered an attempt by Wagner to fabricate a mass grave near Gossi, aimed at tarnishing the reputation of the French military. The claim was that the bodies had been abandoned following the French military’s handover of the Gossi camp to the FAMa.126Jason Burke, ‘France says Russian mercenaries staged ‘French atrocity’ in Mali,’ The Guardian, 22 April 2022

However, the events in Gossi are emblematic of an increasingly complex and hostile information environment in the Sahel in general and in Mali in particular. One that is flooded by disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda following the authoritarian turns resulting from successive military coups in Mali and in neighboring Burkina Faso.

Russian media influence in the Sahel leverage Kremlin-backed outlets like Russia Today and Sputnik to promote Russia as a non-colonizing ally, particularly in French-speaking Africa. These media outlets frequently contrast Russia against European countries and amplify ‘anti-French’ narratives.127Adib Bencherif and Marie-Eve Carignan, ‘Exploratory research report on the information environment in a political and security crisis context in the Sahel Region,’ NATO StratCom COE, 2 June 2023 While not the origin of these anti-French sentiments, Russian media outlets strategically exploit and exaggerate these narratives against France as the former colonizer using social media for influence and disinformation campaigns, troll factories, and fake accounts.

In an earlier report, ACLED highlighted the Wagner Group’s introduction of booby-trapping, a tactic not previously employed by any of Mali’s partner forces. Since then, Wagner’s tactics in Mali have further evolved to incorporate more heinous methods, such as the booby-trapping of bodies, the ejection of prisoners from aircrafts, and the destruction of telecommunication antennas in their operational zones.

Wagner’s evolving tactics are accompanied by a continuous diversification of engagements and alliance configurations, encompassing a wide range of activities and cooperation with various entities. Notably, the group has taken part in both independent operations and collaborative efforts with military forces and various local militias, underscoring its evolution and adaptability to different local contexts. Wagner’s engagements range from traditional operations against jihadist militants to military actions against local militias and unidentified armed groups. However, Wagner mercenaries most frequently engage in the targeting of civilians through mass killings, abductions, and looting, indicating Wagner’s considerable involvement beyond traditional combat roles.

While the partnership between the Wagner Group and the self-defense Dan Na Ambassagou militia has consolidated over time, Wagner has also nurtured alliances with other pro-government militias, such as the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defense Group and Allies and the Dawsahak Faction of the Movement for the Salvation of Azawad. In the northern regions of Gao and Menaka, Wagner’s operations only started in the latter half of 2022, where the Wagner Group exhibited significant restraint compared to its activities in central Mali.

Despite the presence of Wagner mercenaries, FAMa soldiers, and pro-government militias in several areas of Gao and Menaka, their impact against IS Sahel remains limited, especially since IS Sahel continues to expand its sphere of influence within these regions. In the town of Menaka, IS Sahel has been able to impose commercial traffic blockades and restrictions on movements, suggesting that the influence of the government-backed forces is limited to the urban area and its immediate surroundings, with occasional patrols and reconnaissance missions.

Despite intense operations of both FAMa and the Wagner Group in the central regions of Mali, ACLED data show that they only had a limited impact on JNIM’s operational capacity. The operational tempo of JNIM’s activities measured in the number of initiated events in Mopti and Segou regions has notably remained consistent over time. This enduring resilience can be attributed to JNIM’s adaptability, particularly by avoiding direct confrontations, seeking to engage in battle on favorable terms through ambushes, adhering to its established doctrine of mine warfare, and predominantly engaging in direct combat with less capable forces such as the Dan Na Ambassagou and other Dozo militias.

The effectiveness of FAMa and Wagner’s counterinsurgency efforts diminishes even further when extending the focus to include JNIM’s operations in the southern and western regions, including Koulikoro, Kayes, and Sikasso. Notably, FAMa and Wagner’s operations have seen most success when air support is involved, despite many such operations targeting civilian populations at markets and in villages.128Among FAMa and Wagner’s most decisive tactical victories are the battles in Korientze, Diallo, and Sevare between February and April 2023. In all these instances, FAMa and Wagner enjoyed air support. Conversely, operations solely involving ground forces have, on multiple occasions, resulted in FAMa and Wagner being routed and forced to retreat. As a result, JNIM has been successful in not only maintaining a high operational tempo but also expanding its geographical scope of operations.

Civilian targeting accounts for 69% of Wagner’s total engagements in Mali. This is followed by 21% of interactions with JNIM and 6% with IS Sahel (see graph below). The lack of reported involvement of Russian partner forces in offensive operations communicated by Malian authorities could be one factor possibly leading to an underrepresentation of Wagner’s participation in military operations against militant groups. Moreover, the communication tactics employed by the Malian authorities often omit essential details in their statements, such as specific event dates, precise locations, and disaggregation of reported operations and their outcomes. Conversely, these military operations and their outcomes are seldom confirmed by other sources, casting Malian official statements as potentially biased single-source reports. This concern is accentuated when local reporting from credible sources provides starkly contrasting versions of the events.

In the first and second quarters of 2023, the number of civilian fatalities attributed to Wagner mercenaries escalated, which were only higher during the months of March-April 2022 and September 2022. The record numbers noted in March-April 2022 were a direct result of the mass atrocities committed in the small town of Moura. During these events, a joint airborne and air-land operation involving Malian special forces and Wagner mercenaries led to the massacre of hundreds of people over five days. In May 2023, a report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights concluded that there is credible and reliable evidence to support the allegations of serious violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law with reasonable grounds to believe that at least 500 people were killed in Moura between 27 and 31 March 2022.129OHCHR, ‘Rapport sur les évènements de Moura du 27 au 31 mars 2022,’ May 2023 Moreover, the staged mass grave in Gossi in April 2022 came only days after a massacre in the town of Hombori, during which at least fifty civilians were reportedly killed at the hands of FAMa and Wagner, and more than five hundred were arrested. The killings and mass arrests came in retaliation for an improvised explosive device attack claimed by JNIM, which killed one Wagner mercenary and wounded at least one Malian gendarme.

However, Wagner mercenaries have also been involved in the pillaging of local populations, including large-scale, organized cattle theft. A previous ACLED report underscored the emergence of a tripartite coalition between FAMa, Wagner, and the predominantly ethnic-Dogon Dan Na Ambassagou (for more, see ACLED’s Actor Profile: Dan Na Ambassagou). This alliance has solidified over time, with Wagner’s partnership with Dan Na Ambassagou playing a critical role in extensive cattle-rustling campaigns across central Mali. Wagner also routinely extorts local businessmen and appropriates valuables, cash, and other possessions from residents and marketgoers. These actions prompted inquiries as to whether Wagner’s systematic looting and cattle theft serve to partially offset its monthly fee or compensate for any outstanding payments from the Malian authorities.130RFI, ‘Mali: soldats maliens, russes et chasseurs dozos accusés de vols massifs de bétail,’ 24 November 2022

Local insights gathered over the past three months add further nuance to the evolving dynamics. The Wagner Group relies on a network of local informants and collaborators to target communities suspected of colluding with jihadist militants. A group predominantly made up of former IS Sahel members hailing from the Idourfane community, who have been instrumental in guiding Wagner and FAMa during their door-to-door operations in the surroundings of Ansongo.131Personal communications with community source, May 2023 Similarly, in the Douentza region, local sources suggest a surge in the number of Fulani youths becoming Wagner collaborators and informants. This unexpected alliance, while initially surprising, may be indicative of underlying socio-political dynamics in the region, reflecting an evolving and possibly pragmatic response to the challenging security environment. The exact nature of these collaborations, their implications, and the motivating factors for these Fulani youths require further investigation.

The shift towards the Wagner Group’s greater public profile in late 2022 elevated the recognition of the organization and coincided with its increasing involvement in military activity prior to the attempted mutiny in June 2023. The Wagner Group’s march towards Moscow over Prigozhin’s reluctance to cede control of the organization to the MoD has been so far short-lived and abortive. Prigozhin’s lucrative catering contracts with the MoD and other government entities were canceled, while Prigozhin appeared to have culled his media empire to prevent its takeover by others. In light of the potential for major changes to the Wagner Group in the future, this report has outlined the local contexts that have enabled Wagner’s operations worldwide, drawing on the major engagements within CAR, Mali, and Ukraine.