Follow us on:

Follow us on:

Follow us on:

Kitco Commentaries | Opinions, Ideas and Markets Talk

Featuring views and opinions written by market professionals, not staff journalists.

Commentaries & Views

Share this article:

Copper is one of the most important metals with more than 20 million tonnes consumed each year across a variety of industries, including building construction (wiring & piping,) power generation/ transmission, and electronic product manufacturing.

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for the orange metal even further. More copper will be required to feed our renewable energy infrastructure. The metal is also a key component in transportation, and with increasing emphasis on electrification, demand is only going to increase.

But there’s a problem. A major rise in copper demand from new “blacktop” infrastructure (think roads, bridges, airports, etc.), combined with high demand for copper from large-scale efforts on behalf of governments to decarbonize and electrify, is not being met with an adequate supply of the industrial metal. Trillions worth of new projects are thus in danger of falling by the wayside unless much more copper is discovered — more than is currently possible, in my opinion.

My position is supported by a recent report from S&P Global, which predicts the world’s appetite for copper will reach 53 million tonnes, on an annual basis, by mid-century. This is more than double current global mine production of 21Mt, according to the US Geological Survey.

How are we going to find the copper?

Although EV market share is still tiny compared to traditional vehicles, that is likely to change in the coming years as major economies transition away from fossil fuels and move into clean energy.

US President Joe Biden has signed an executive order requiring that half of all new vehicle sales be electric by 2030. China, the world’s biggest EV market, has a similar mandate that requires electric cars to make up 40% of all sales. The European Union is also seeking to have at least 30 million zero-emission vehicles on its roads by then.

According to the IEA’s Global Electric Vehicle Outlook, if governments are able to ramp up their efforts to meet energy and climate goals, the global electric vehicle fleet could reach as high as 230 million by the end of the decade, compared to about 20 million currently.

With more electric cars comes the need for more raw materials like copper, lithium, nickel and graphite to build batteries. The IEA believes mineral demand for use in EVs and battery storage must grow at least 30 times by 2040 to meet various climate goals.

Fastmarkets forecast that EV sales will experience a compound annual growth rate of 40% per year through 2025, when EV penetration is expected to reach 15%. After that, EV market share is expected to rise further, reaching 35% by 2030.

One mineral that has been overlooked, but is an essential part of vehicle electrification, is graphite.

At AOTH, we believe graphite represents a “backdoor” market opportunity brought about by the clean energy transition.

This article focuses on the copper and graphite markets, and why making an investment in them now could be a very wise move.

Copper

It’s not an exaggeration to say that copper is essential to decarbonization; nothing happens without it. The continued movement towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. EVs use about 4X as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles. It’s in the motor, the wiring, and the charging stations. Copper is also in the “smart grid” to get renewable energy to where it’s needed. The latest use for copper is in renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

Bullish long-term

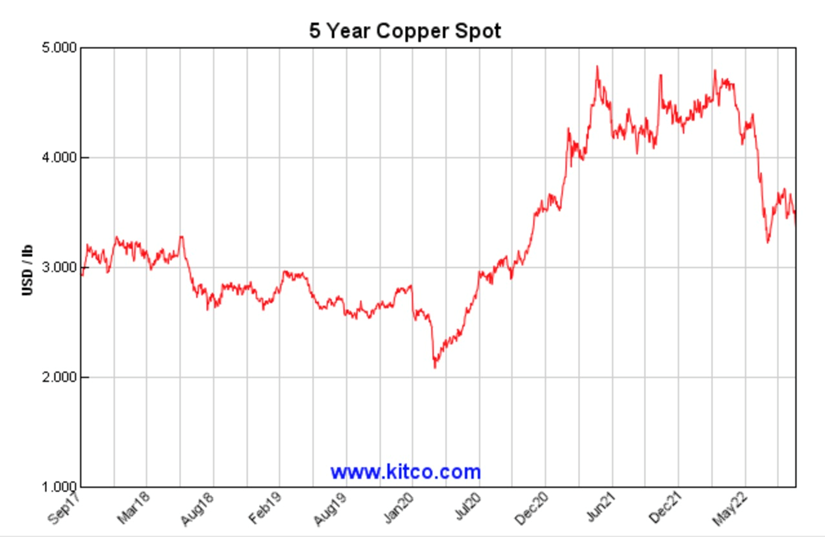

Although the copper price has retreated from a record-high $5.02 a pound, reached in March, the bull market for copper remains fundamentally intact — bolstering the case for investing in companies that mine the orange metal and exploration companies (“copper juniors”) that explore for it.

Copper fundamentals strong despite price weakness Source: Kitco

Source: Kitco

Copper is a bellwether for the health of the global economy because it has so many industrial uses. Funds historically have bought and sold copper futures as a proxy for global growth. The combination of an actual and expected global slowdown (the OECD’s outlook this week has global growth increasing at a modest 3% this year before slowing to just 2.2% in 2023), and the US dollar at near-record highs, has pushed copper prices down about 30% so far this year. Another bearish signal right now is backwardation. On Sept. 8 Bloomberg reported the premium for cash copper over three-month futures on the LME nearly doubled to a high of $145 per tonne — the biggest backwardation since November 2021. Backwardation means there is an expectation that the current spot price is too high and that the future spot will fall.

Despite these negatives, physical copper supplies remain tight. According to customs data from China, the world’s largest consumer of the metal, copper imports were up 8.1% in the year to August.

“It doesn’t feel to me that anyone wants to be caught short on a price rally because the physical market is actually very strong,” Bloomberg quoted Michael Widmer, head of metals research at Bank of America. He added: “Europe is spending as much as possible on grids and renewables to become energy independent from Russia and China’s doing the same for de-carbonization reasons.”

“Copper is the metal of electrification and absolutely essential to the energy transition,” says Daniel Yergin, vice chairman for S&P Global, regarding the above-mentioned study, via Reuters.

The firm forecasts global copper demand from solar and wind energy will reach 852,000 tonnes this year, while the burgeoning EV market will account for 1.1 million tonnes. Sales of electric vehicles almost doubled from 2020 to 2021, led by China and Europe.

Longer term, S&P expects copper demand from the energy transition will jump to about 21Mt in 2035, nearly triple the current 8Mt. Driving the growth will be EVs, EV charging equipment, and a buildout of the transmission and distribution system.

Meanwhile, demand for copper from traditional uses is also expected to rise. As we reported previously, this is due to the need for countries to reduce their so-called “infrastructure deficits”. Basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, has been poorly maintained, and requires hefty investments, measured in trillions of dollars, to repair or replace.

As infrastructure needs multiply, copper supply can’t keep up

China, the world’s biggest commodities consumer, has committed to spending at least US$2.3 trillion this year on major infrastructure projects. They are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy. More money will be aside in years two to five. Note that China’s current infrastructure spending commitment for 2022 alone, is nearly double the United States’ which last November passed a US$1.2 trillion infrastructure package.

There is also the Made in China 2025 initiative, which seeks to end Chinese reliance on foreign technology by investing in a number of key sectors, including IT and robotics, and China’s $900 billion “Belt and Road Initiative”, designed to open channels between China and its neighbors, mostly through infrastructure investments. Dozens of countries have signed up to it, including Russia.

Research commissioned by the International Copper Association, quoted by Mining Technology, found that Belt and Road projects in over 60 Eurasian countries will push the demand for copper to 6.5 million tonnes by 2027.

That much copper equates to nearly a third of the 21Mt of copper produced in 2021 — new copper supply that would need to be either mined from existing operations or discovered.

The US is pursuing its own $1.2 trillion infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is the largest expenditure on US infrastructure since the Federal Highways Act of 1956. Rolled out over 10 years, it includes $550B in new spending. According to S&P Global, Among the metals-intensive funding in the legislation is $110 billion for roads, bridges, and major projects, $66 billion for passenger and freight rail, $39 billion for public transit, and $7.5 billion for electric vehicles.

Again I have to ask, where are we gonna find the copper?

The obvious answer is, mine more, but that is easier said than done.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance (NEF) estimates that in 20 years, the world’s copper miners must double the amount of global production — from the current 20 million tonnes annually to 40 million tonnes — just to match the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles.

This is a tough ask considering some of the world’s largest mines are seeing depleted copper reserves and lower ore grades, so it would be difficult for global production to even maintain a 20-million-tonne-per-year pace.

Bank of America in a recent report predicts the copper market will flip into a deficit as early as 2025 following the completion of the current wave of project buildouts, the latest being Ivanhoe Mines’ massive Kamoa-Kakula project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Short-term copper supply will be bumped up by newly established copper mines that are expected to begin production soon. They include the Timok Mine in Serbia and the Mina Justa Mine in Peru.

“While visibility over the near-term project pipeline is good, activity increases come with a wrinkle,” the bank’s analysts say. “Indeed, many of the projects currently developed have been in the making for almost three decades, and with exploration activity relatively limited in recent years, supply increases may fade from 2025.”

Five years later, analysts at Rystad Energy project that copper demand will outstrip supply by more than 6 million tonnes. That equates to nearly the entire annual production of Chile, the world’s top producer.

By 2040, the supply shortfall grows to 14Mt, according to a BloombergNEF August report, with a “best-case scenario” shortage of >5 million short tons possible by 2040.

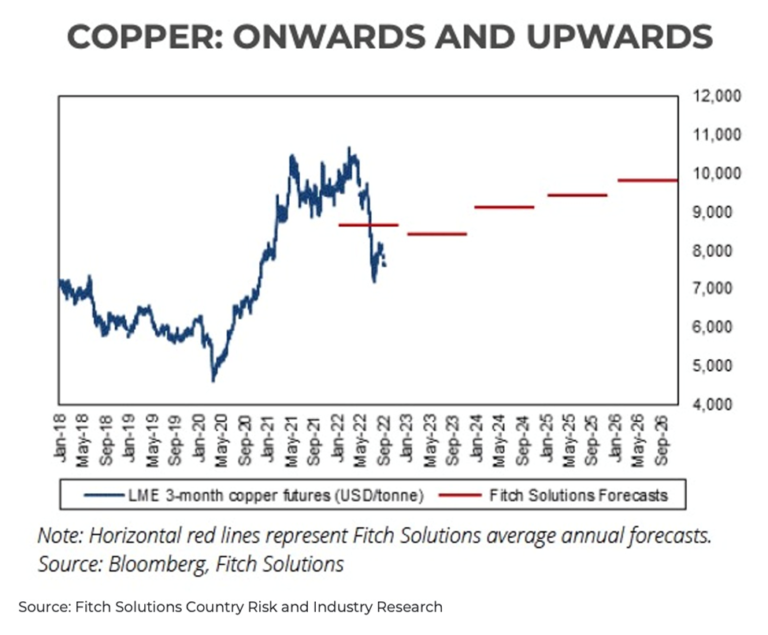

As for what the supply challenges mean for copper prices going forward, a new report from Fitch Solutions cuts the research firm’s copper price forecast next year to $8,400 a ton, down from its previous projection of $9,580/t (on average), as the copper market registers a small surplus in 2022.

However, Fitch expects growing deficits from 2023 onwards, peaking at 9 million tonnes by the end of the decade, as demand accelerates, “mainly driven by consumption related to the green transition.”

The firm also sees steady improvement in prices over the next five years, with the metal returning to its March peaks above $10,000/t in 2027 and $11,500 in 2031 as “a long term structural deficit emerges.”

Majors diversifying

As global growth slows and talk of a recession becomes louder, falling metal prices, including gold, which recently scraped a two-year low, are forcing companies into a defensive posture, as they seek to maintain profit margins during what could be a prolonged downturn.

Diversification is the new mining buzzword

Agnico Eagle Mines is teaming up with Teck Resources to buy a copper-zinc project in Mexico, in what would be a major departure from precious metals for Agnico. The Toronto-based company, with stock symbol AEM, has said it will pay USD$580 million for a 50% share in Teck’s San Nicolas copper-zinc mine in Zacatecas, Mexico.

The Globe & Mail notes that AEM, Canada’s second-biggest gold producer, is currently heavily weighted to precious metals production (about 99%), but once San Nicolas starts up, precious metals would fall to 87% of the company’s output.

Agnico is not alone in increasing its exposure to copper and other green-economy metals, including lithium, graphite and nickel.

Teck Resources, for example, is moving its business away from coal and oil, towards copper by building a major new copper mine in Chile, called Quebrada Blanca, or QB2.

About 20% of Barrick Gold’s production now comes from copper, and, in 2020 CEO Mark Bristow indicated his interest in Grasberg, US copper mining giant Freeport McMoRan’s flagship asset in Indonesia.

The Financial Post reported that Bristow several years ago engaged in unsuccessful merger discussions with Freeport-McMoran. The CEO reiterated his interest in the base metal. “Copper is probably the most strategic metal, and it’s geologically related to gold,” he said. “So if you want to become a world-leading gold company in the fullness of time, you are going to end up producing [copper].”

While not a gold company, earlier this month Rio Tinto said it is willing to pay $4.2 billion to buy the 49% of Canadian producer Turquoise Hill Resources it doesn’t already own, effectively giving the Anglo-Australian multinational control of the massive Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold mine in Mongolia (Turquoise Hill owns 66% of Oyu Tolgoi, with the Mongolian government holding the remaining 34% interest).

Investors Chronicle said the latest round of diversification among major miners differs from the last mining boom, when the majors tried building non-iron ore projects that would address short and medium-term market conditions, such as oil and gas.

This time it’s different: BHP and Anglo are looking at population growth and more hungry mouths as drivers, while the lithium plan from Rio is largely based on forecast battery manufacturing capacity in Europe.

A report earlier this year from Fitch Solutions confirms that the mining majors are ramping up their diversification policies to capitalize on decarbonization trends.

A non-copper example is Rio Tinto’s Jadar lithium-borate mine project in Serbia. Despite opposition from environmentalists, the Anglo-Australian mining group is reportedly working on a feasibility study and with US-based Bechtel on project design.

Graphite

The three most critical inputs in the race to electrify and decarbonize the globe are copper, lithium and graphite.

Graphite is included on a list of 23 critical metals the US Geological Survey has deemed critical to the nation’s economy and national security. The EU has also designated graphite a critical mineral.

The lithium-ion battery used to power electric vehicles is made of two electrodes — an anode (negative) on one side and a cathode (positive) on the other. At the moment, graphite is the only material that can be used in the anode, there are no substitutes. It is also the largest component in lithium-ion batteries by weight, meaning a battery takes 10 to 15 times more graphite than lithium.

An average plug-in EV has 70 kg of graphite. Every 1 million EVs requires about 75,000 tonnes of natural graphite, equivalent to a 10% increase in flake graphite demand.

“Overall, we expect the total lithium-ion battery market to grow by 35% in 2022 to 602 gigawatt hours,” Suzanne Shaw from commodities consultant Wood Mackenzie told Investing News Network earlier this year. “Such large growth will allow room for significant rises in both natural and synthetic graphite.”

A White House report on critical supply chains showed that graphite demand for clean energy applications will require 25 times more graphite by 2040 than was produced in 2020.

It’s thought that battery demand could gobble up well over 1.6 million tonnes of flake graphite per year (out of a 2021 market, all uses, of 1Mt). Remember, the mining industry still needs to supply other graphite end-users. Currently, the automotive and steel industries are the largest consumers of graphite with demand across both rising at 5% per annum.

INN quoted Benchmark Mineral Intelligence data showing demand for natural graphite from the battery segment amounted to 400,000 tonnes in 2021, with that number expected to scale up to 3Mt by 2030. Demand for synthetic graphite came to about 300,000 tonnes in 2021, and is expected to increase to 1.5Mt by 2030.

According to the US Geological Survey, output has increased in response to strong demand from the lithium battery market and increased prices. But just to supply Tesla’s expected 100 million EVs, by 2032, would require 6X the amount of lithium currently being mined.

Where are the EV makers going to find the graphite? Remember even if they could, they will not find the needed copper.

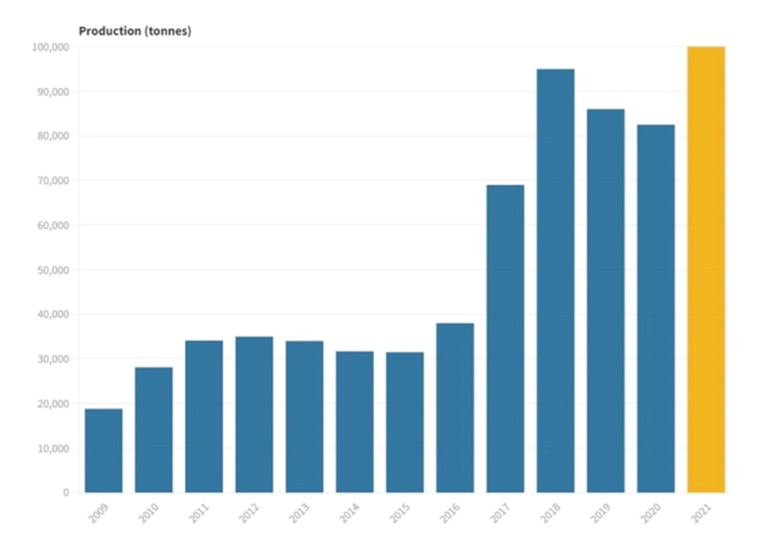

Global graphite production in thousand metric tons. Source: USGS

Battery demand could gobble up well over 1.6 million tonnes of flake graphite per year (out of a 2021 market, all uses, of 1Mt) — only flake graphite, upgraded to 99.9% purity, and synthetic graphite (made from petroleum coke, a very expensive process) can be used in lithium-ion batteries.

Global graphite consumption has been increasing steadily almost every year since 2013.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the flake graphite feedstock required to supply the world’s lithium-ion anode market is projected to reach 1.25 million tonnes per annum by 2025. At this rate, demand will easily outstrip supply in a few years.

Analyst Visual Capitalist Elements, via Battery & Energy Storage Technology, says demand for graphite from battery makers is expected to expand 10.5-fold to 2030. They forecast the natural graphite market could be in deficit as early as 2023, due to a shortage of new sources outside China.

China is not only the world’s biggest graphite miner, it is also the number 1 refiner, handling a combined two-thirds of global cathode and anode production. Yet even China is feeling the pressure of steady, rising demand — the country in 2019 was a net graphite importer for the first time in its history.

The country currently produces 70-80% of the world’s graphite and 100% of the natural graphite used in lithium-ion batteries. Traditionally, Shandong province was the center of graphite mining but production there is declining due to depleted ore reserves and stricter environmental regulations. Mining has therefore transitioned to another province, Heilongjiang, where small-flake graphite is mainly produced. It’s been reported that the opportunity in the short- to medium-term is in the large and extra-large flake markets, which are high-price and high-margin with supply shortages. Longer term, new Western source of small flake production will be required to meet the expected growth in the EV/ lithium-ion battery markets.

According to Urbix, an American manufacturer of battery anode materials, due to the unprecedented global demand for lithium-ion batteries, a shortage of battery-grade graphite is expected as soon as this year. (graphite is predicted to remain the predominant anode material regardless of a battery’s cathode chemistry)

Even the so-called experts are wrong about critical metals supply

US government on board

The US, which has long sought to improve its battery supply chain, earlier this year invoked its Cold War powers by including lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite and manganese on the list of items covered by the 1950 Defense Production Act, previously used by President Harry Truman to make steel for the Korean War.

To bolster domestic production of these minerals, US miners can now gain access to $750 million under the act’s Title III fund, which can be used for current operations, productivity and safety upgrades, and feasibility studies. The decision could also cover the recycling of these materials, according to Bloomberg sources.

The Biden administration has already allocated $6 billion as part of the trillion-dollar infrastructure bill, towards developing a reliable battery supply chain and weaning the auto industry off its reliance on China, the biggest EV market and leading producer of lithium-ion cells.

Recently the administration convened a meeting of the Minerals Security Partnership, formed in June as a sort of “metallic NATO”. Members include the United States, Canada, Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the European Commission.

In fact, the MSP is defined more by who is not on the list — China and Russia.

Bloomberg reports the gathering of resource-rich nations is a way to spur new investment, as part of its bid to shift the supply chain from critical minerals away from China. The initiative is designed to funnel investment towards developing countries that adhere to “ESG” (environmental, social and governance) principles.

Developing nations at the meeting, held at the UN General Assembly in New York, and chaired by US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, included Argentina, Brazil, Chile, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Mongolia, Mozambique, Namibia, the Philippines, Tanzania and Zambia.

The partnership buttresses funds made available for critical minerals through Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), signed into law last month. Battery upstarts are reportedly salivating over the goodies in the bill, particularly the tax credits for manufacturing components here in the US…

(Starting on Jan. 1, 2023, $10 billion in tax credits will be provided. The tax credit is 30% of the amount invested in new or upgraded factories to build specified renewable energy components)

Kurt Kelty, a Tesla and Panasonic veteran, told Bloomberg his battery startup Sila Technologies has seen more serious interest from automakers looking to procure battery materials domestically. Same for Mitra Chem, a Silicon Valley company aiming to produce lithium iron phosphate cathodes in the US. There’s a months-long wait list for samples, and the firm is already scouting sites for a new factory, CEO Vivas Kumar said.

However, the auto industry is concerned that content rules will limit how many EVs will be eligible for consumer tax credits. Companies are also anxious that if the US goes too far in trying to cut out China, their products could be vulnerable to retaliation.

Two ideas under debate are a “white list” of domestic battery manufacturers whose products are eligible for subsidies (something China did successfully); and a “battery passport” similar to what’s been proposed in Europe. It would involve setting up digital tracing for all the raw materials in a battery, to ensure compliance with environmental and labor standards. A passport would end up excluding countries with questionable mining records, such as Indonesia and the DRC.

Conclusion

A global graphite shortage is a matter of when, not if, without new sources of supply. For the US, which is 100% dependent on foreign imports of the material, it’s a ticking time bomb that could derail the nation’s vehicle electrification and decarbonization ambitions.

This all goes back to the importance of establishing a reliable, secure and sustainable “mine to battery” EV supply chain, beginning with a domestic graphite source and integrating it with processing, manufacturing and recycling to create a full circular economy.

Recently, the US Geological Survey cited the Graphite Creek resource near Nome, Alaska, as the largest known graphite deposit in the country. It is part of an integrated project proposed by Graphite One (GPH:TSXV; GPHOF:OTCQX), which aims to mine and process the graphite and build an advanced materials and battery anode manufacturing plant in Washington State. Graphite One was granted “High-Priority Infrastructure Project” status in January by the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Committee (FPISC), which would allow the company’s approval process to be streamlined.

Over the summer Graphite One underwent a major de-risking event with the release of the prefeasibility study (PFS) for its Graphite One Project. 2021 drilling has successfully upgraded the 2019 resource estimate, delivering nearly a 200% increase in measured and indicated resources. The PFS also portrays the Graphite One Project as highly profitable, with expected costs of $3,590 per tonne measured against an average graphite product price of $7,301 per tonne.

“With the growing demand for graphite in electric vehicle batteries and other energy storage applications – and recent actions by the Biden administration to secure U.S. supply chains for critical minerals – we see Graphite One’s aim to produce a U.S.-based supply chain solution becoming increasingly significant as a new potential source of advanced graphite products for decades to come,” says Anthony Huston, Graphite One’s President & CEO.

Graphite One releases prefeasibility study for Graphite Creek Mine and Washington State battery anode materials manufacturing facility

The expected shortfall in copper supply and the inability of recycling to fill the gap, measured against robust demand for copper from both traditional and so-called “green” applications (mainly electric vehicles and renewable energy) bodes well for companies exploring for copper. After all, they are the owners of the world’s next copper mines.

At AOTH, our favorite copper junior is Max Resources (TSXV:MAX; OTC:MXROF; Frankfurt:M1D2), known for its CESAR copper-silver project in northeastern Colombia.

The URU discovery spans a major structural corridor and remains open in all directions. Geologically, Max compares the sediment-hosted copper-silver mineralization at URU to that found in the Central African Copper Belt (e.g., Ivanhoe Mines’ 95-billion-pound Kamoa-Kakula copper deposit in the DRC).

Sitting on about a $20 million treasury, the company is poised to drill CESAR for the first time this month. I’m expecting major news flow from Max as assay results from URU are received. They should, imo, provide plenty of evidence backing up CESAR’s extremely unique geological model, and the potential of building out a large resource.

Max Resources identifies two very significant initial drill targets at CESAR’s URU District

Making a successful investment in the resource sector involves a number of factors, including having an experienced management team, the right metal(s), favorable geology and a low-risk jurisdiction. Unfortunately, even if all these aspects line up in a quality company, you also need to time your buy-in.

Lately there have been a lot of negative headlines about a coming recession. Resource investors who run with the herd may choose to take their profits, if any, and exit the market. The fearful will stay in cash, while the hopeful will look for opportunities.

It may seem illogical to even consider commodities during current market conditions. Both the energy and materials sectors are considered very economically sensitive. Industrial metals copper, aluminum, zinc and lead have all seen YTD declines.

Another reason metals have been selling off, is investors looking back at the Great Recession of 2007-09 as a guide. The recession was notoriously bad for commodities. Materials and energy were two of the worst sectors in the S&P 500, crumbling 60% between May 2008 and March 2009. When investors first heard calls for recession a few months ago, these areas were once again targeted for liquidation.

It’s a decision they may live to regret. Using the 2008 playbook risks selling commodities at the bottom of a cycle, missing huge potential returns over the coming decade.

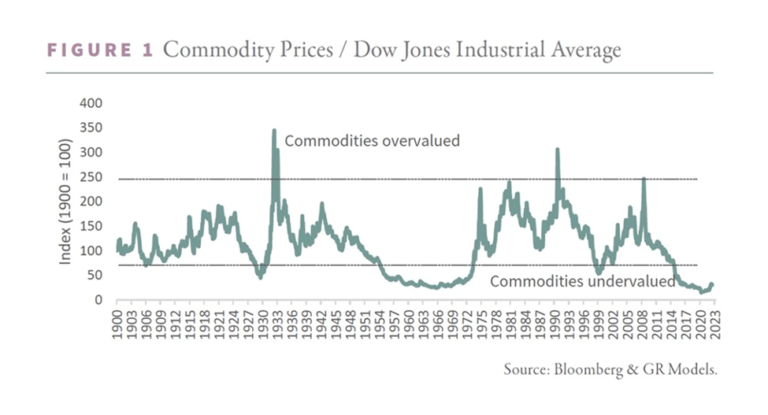

That’s because, when investing in natural resource equities, the commodity capital cycle is more important than the broader economic cycle. I found the chart below in a recent report from Goehring & Rozencwajg, the Wall Street natural resource investment firm.

Buy signal flashing for undervalued commodities

The chart shows the relationship between the Dow Jones Industrial Average and a commodity index going back several decades. It clearly indicates periods when commodities are extremely undervalued or overvalued – compared to the Dow. In places where the green line falls under 75, commodities are cheap relative to financial assets. These periods typically represent bear markets for commodities. The chart shows the most undervalued years for commodities were 1929, 1969, 1999 and 2020.

Notice that commodities are extremely undervalued when the green line dips below the black line indicating a value of 75. In 1930, for example, when the Great Depression started, from 1954 to 1972 — a very long bear market for commodities — in 1999, and from about 2015 to 2020.

Right after the dips though, the green line shoots higher. We see this most prevalently in 1932, 1973, 1981, 1991 and 2008. Commodity prices are seen drifting lower for about a decade from 2010, reaching a nadir with the coronavirus economic crisis of early 2020.

But as we know from recent history, economic recovery from the pandemic, combined with trillions worth of direct and indirect government stimulus, pushed demand for goods and services higher than supply, creating a boon for commodities along with the highest levels of inflation in 40 years. This is represented by the slight uptick on the right of the chart.

The key point is that even if we were to go into another recession, it doesn’t necessarily mean that commodity prices will fall in lockstep, as they did in 2008. In fact, they (and resource equities) are likely to hold their own and do quite well, because unlike in 2008, commodities are undervalued, shown on the chart as the green line falling below 75 in 2015 and staying there until 2020, when they began trending up again.

In terms of G&R’s commodity capital cycle described above, we are currently in the stage of depletion, when supply falters, demand grows, and inventory gluts gets worked off. The stage is, imo, set for the next bullish cycle to start.

In their report, G&R maintain that The radical undervaluation of commodities and commodity related equities is greater now than it was back in 1929, and the level of capital starvation is just as great. History tells us that commodities could again be an excellent place to seek high returns, even if the 2020s experience a period of economic turmoil as severe as the Great Depression — a scenario we consider unlikely.

G&R’s Commodity Prices/ Dow Jones Industrial Average chart shows that there hasn’t been a better setup for commodities than now, over a time frame spanning 120 years. Especially when you consider the current rout in the stock market and the pummeling juniors are taking.

In a recent commentary, 321gold’s Bob Moriarty wrote:

With the penny juniors in the mining area falling off a cliff on Friday with massive drops across the board, we are starting to see capitulation. While it is painful to watch your investments dropping by double digits daily, this is where wise investors make their fortunes. The market will rocket higher just as soon as those silly investors who used margin finish selling off the last of their investments just to meet a margin call.

These sorts of opportunities only come once in a lifetime. Prepare yourself to rake up the falling fruit. This is a quote from Basic Investing in Resource Stocks.

“Weak hands buy at tops and sell at bottoms. Strong hands buy at bottoms and sell at tops. It’s vital that investors remember that at every top there are 50 reasons to buy, and at every bottom there are 50 reasons to sell. That’s what makes them tops and bottoms.”

I personally can’t think of a better time to pick up deeply undervalued and high-quality junior mining companies that are poised to capitalize on the decarbonization and electrification trends that are central to the new economy. At AOTH, our two favorite plays rights now are Max Resources for copper and Graphite One for graphite.

Contributing to kitco.com

Interactive Chart

Kitco

Connect

Tools

We appreciate your feedback.

How can we help you? 1 877 775-4826

Drop us a line [email protected]