Situation Update | April 2023

14 April 2023

< Back to Sudan Hub

Since the ouster of former President Omar al-Bashir in April 2019, Sudan has experienced a turbulent political transition. Following the uprising that led to al-Bashir’s removal, the Sudanese military and a coalition of civic groups united under the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) established a transitional government to lead the country toward a democratic and civilian government. However, the transition has suffered multiple setbacks, including political unrest, rising economic instability, and a military coup on 25 October 2021 that dismantled the civilian institutions and overturned parts of the previous power-sharing arrangement.1Sami Abdelhalim Saeed, ‘Sudan’s Constitutional Crisis: Dissecting the Coup Declaration,’ Just Security, 3 November 2021 In December 2022, military and civilian political actors signed a framework agreement to relaunch the political process for Sudan’s transition to a civilian government. This report analyzes the political developments of the transition process and the resulting shifts in patterns of disorder nationwide, with unrest declining in the capital Khartoum and surrounding areas, and new actors involved in violent activity.

Following the 2021 military coup and the resignation of former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok in January 2022,2Al Jazeera, ‘Sudan’s Hamdok resigns as prime minister amid political deadlock,’ 2 January 2022 the United Nations brokered a consultation process involving a wide range of Sudanese stakeholders to overcome the political crisis.3UN Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan, ‘Consultations on a Political Process for Sudan: An inclusive intra-Sudanese process on the way forward for democracy and peace,’ 28 February 2022

In December 2022, after mounting unrest and international pressure, 40 actors representing political and civil society actors as well as armed groups and the Sudanese military signed the framework agreement.4Hamid Khalafallah, ‘Sudan’s Post-Coup Crisis: From a Political Impasse to an Unpopular Political Process,’ Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, 14 March 2023 Many political actors, including foreign embassies, welcomed it as a step toward restoring civilian rule in Sudan.5Michael Young, ‘Will the Framework Deal Between Sudan’s Military Rulers and Civil Opposition Restore Civilian Rule?,’ Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, 12 January 2023 The agreement calls for establishing a transitional civilian government, identifying five pillars: accountability and transitional justice; security and military reform; implementation of the Juba Peace Agreement (JPA) between the government and the armed groups signatory to the agreement in accordance with the political declaration signed with the non-signatories; dismantling the structures of the “30 June regime” under Omar al-Bashir based on the principles of rule of law and basic rights; and resolving the crisis in eastern Sudan.6Al-Sudan al-Youm, ‘The text of the document and the terms of the framework agreement between the civilian forces and the military in Sudan,’ 5 December 2022 However, some political groups – including most resistance committees, the National Congress Party, and the Democratic Bloc – opposed the agreement.7Karam Said, ‘Political agreement signed in Sudan,’ Ahram Online, 13 December 2022 Differences emerged within the Transitional Military Council (TMC), with Commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Daglo (known as Hemeti), calling the 25 October military coup, which deposed Prime Minister Hamdok, a “political mistake,” while Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the Sudanese army commander, saw it as necessary.8Sudan Tribune, ‘Burhan, Hemetti differ on coup assessment but back Sudan’s framework agreement,’ 5 December 2022 The leader of the Supreme Council of Beja Native Administrations also rejected the agreement and accused the RSF commander and the FFC of dividing the leaders of eastern Sudan.9Sudan Tribune, ‘“Terik” accuses influential people of dividing the leaders of eastern Sudan and fabricating supporters of the “framework,”’ 21 December 2022

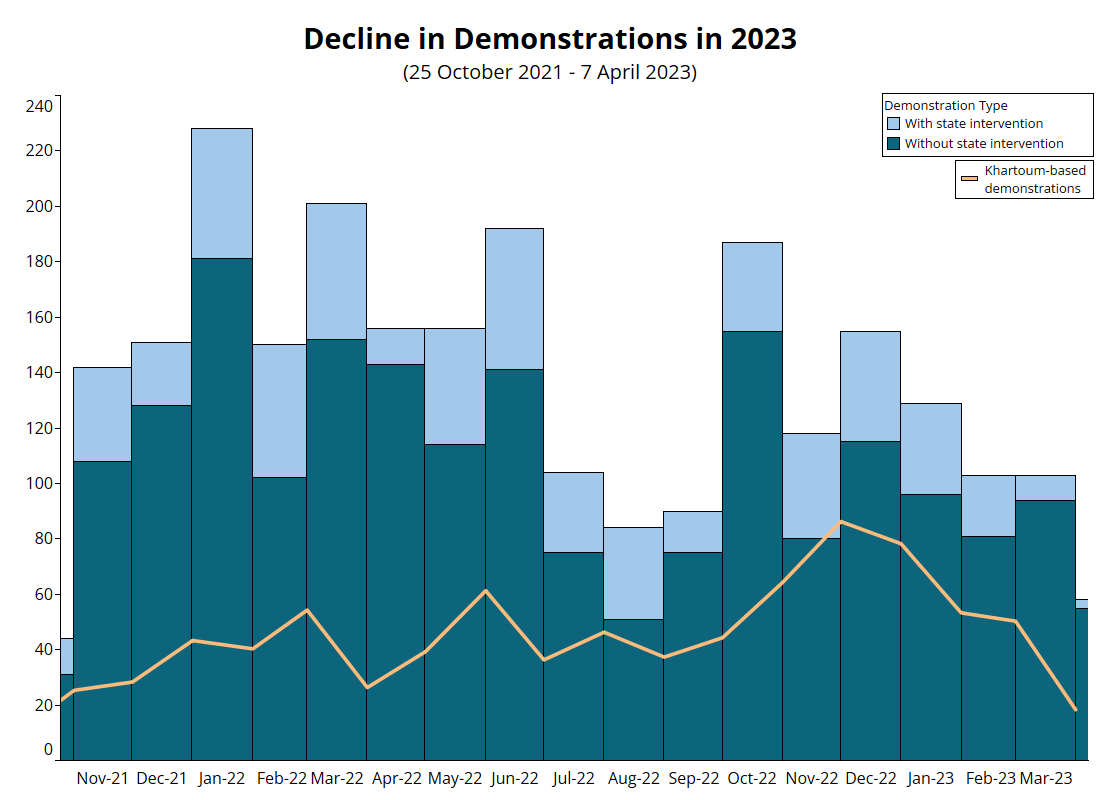

Unrest has declined in the country overall since the signing of the framework agreement. Prior to that, ACLED records an increase in demonstration activity in Sudan after the 25 October 2021 military coup, which reached a peak in January 2022. From 25 October 2021 until 31 December 2022, resistance committees organized as informal neighborhood networks staged demonstrations against the coup demanding a civilian government in at least 90 locations across the country. Security forces intervened in nearly 30% of these demonstrations, resulting in at least 114 reported fatalities. Demonstration activity, however, has declined since January 2023 overall, particularly in Khartoum state. Notably, state intervention in demonstrations has also decreased since the end of 2022 (see graph below). In particular, from 1 January to 7 April state intervention in demonstrations decreased by over 40% compared to the same time period prior. Moreover, ACLED records fewer reported fatalities associated with demonstration activity – at least five this year. Additionally, the issues driving demonstrations have become more varied and disconnected from national-level politics, and more about local and professional demands. Despite the declining trend since the end of 2022, there was an uptick in demonstration activity last week as resistance committees organized protests in at least 26 locations across Sudan – including nationwide demonstrations on 6 April coinciding with the anniversary of uprisings in 1985 and 2019.

The framework agreement stipulates a two-year transitional period during which the military would relinquish power to civilians, ending with democratic elections. It also initiates a process of consultation through workshops, which were held in March with the support of the Trilateral Mechanism of the African Union, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, and the UN.10UN News, ‘Sudan holds massive political ‘workshops’, embarks on new transition phase, Security Council hears,’ 20 March 2023 The workshops focused on five contentious issues in the framework agreement. A diverse group of Sudanese citizens from across the country and from different social, professional, and political backgrounds participated in the workshops. The workshops aimed to ensure that all Sudanese citizens, including marginalized populations, had a voice in the decision-making process.11UNITAMS, ‘Security Council remarks Special Representative of the Secretary-General to Sudan and Head of UNITAMS, Mr. Volker Perthes,’ 20 March 2023

The Final Agreement Drafting Committee, consisting of representatives from the FFC-Central Council, and representatives from the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF, announced the completion of the first draft of the final political agreement on 25 March.12Radio Dabanga, ‘Committee to present draft final agreement to Sudan’s civil and military actors,’ 26 March 2023; Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese parties complete drafting final political agreement,’ 25 March 2023 The draft was based on the recommendations from the participants of the four workshops, the transitional constitution,13Radio Dabanga, ‘Committee to present draft final agreement to Sudan’s civil and military actors,’ 26 March 2023 the framework agreement, and the political declaration regarding three ‘non-signatory’ parties – the Minawi-led faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A), the Justice and Equality Movement, and the Democratic Unionist Party.14Radio Dabanga, ‘Signatories, non-signatories finalise declaration on Sudan Framework Agreement,’ 12 February 2023 The final workshop on security and military reform, however, failed to reach an agreement.15Sudan Tribune, ‘Divergences over RSF’s integration timeline delay security workshop recommendations,’ 29 March 2023 The main disagreement was reportedly over the timeline for its integration, with the SAF suggesting a two-year transitional period while the RSF proposed 10 years.16Al Jazeera, ‘Sudan factions delay post-coup deal on civilian rule,’ 1 April 2023; Mat Nashed, ‘The unlikely prospect of civilian rule in Sudan,’ The New Arab, 5 April 2023

The RSF is a paramilitary force established in 2013 in response to anti-government rebel movements in Darfur and has been accused of human rights abuses in Darfur and elsewhere. In the four years since the ouster of al-Bashir, the RSF has been involved in over 155 civilian targeting incidents and over 300 reported civilian fatalities. Just in one incident, a violent crackdown on protesters on 3 June 2019 by security forces, including the RSF, reportedly killed over 100 civilians and injured hundreds. The RSF has also been accused of arbitrarily detaining civilians, with Human Rights Watch calling on Sudan’s transitional government to “rein in” the RSF.17HRW, ‘Sudan: Unlawful Detentions by Rapid Support Forces,’ 1 March 2021 Integrating the RSF into the army – although admittedly not sufficient on its own – is not only a central demand of civilian groups but critical for paving the way to a stable and peaceful political environment in Sudan.

Consequently, disagreement over the RSF’s integration into the army has delayed the planned signing of the final political agreement twice, on 1 and 6 April, and no new signing date has been set as of the time of writing.18Reuters, ‘Signing of Sudan political agreement delayed to April 6,’ 1 April 2023; Deutsche Welle, ‘Sudan delays signing civilian rule agreement,’ 6 April 2023 It also has raised concerns about the SAF and RSF’s commitment to the ongoing political process.19Sudan Tribune, ‘Divergences over RSF’s integration timeline delay security workshop recommendations,’ 29 March 2023; Declan Walsh, ‘2 Generals Took Over a Country. Will They Deliver Democracy or War?,’ 6 April 2023 Furthermore, the possibility of further instability in the country remains, as resistance committees organized local and nationwide demonstrations, and as troop movements by both sides were reported in the capital.20Declan Walsh, ‘2 Generals Took Over a Country. Will They Deliver Democracy or War?,’ New York Times, 6 April 2023

Since the overthrow of al-Bashir, Sudan’s peripheries have witnessed different rounds of violence taking place amid a scramble for political control, followed by peace consultations sponsored by the security apparatus, especially the RSF and its leader, Hemeti.21Mat Nashed, ‘‘Justice has to happen first’: Why Darfuris are rejecting a local reconciliation drive,’ The New Humanitarian, 8 February 2023 These territories are often under the control of rebel or paramilitary groups, which have extractive interests in their respective local economies. As part of the democratic and peace-building arrangements put in place for the transitional period, the JPA was signed between several rebel groups and the transitional government on 3 October 2020. The JPA aimed to end conflicts in Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile, and start the transition process.22Fergus Kell, ‘Sudan’s Juba Peace Agreement: Ensuring implementation and prospects for increasing inclusivity,’ 7 December 2020 Over two years since the signing of the JPA, Sudan is getting closer to signing a comprehensive political agreement.

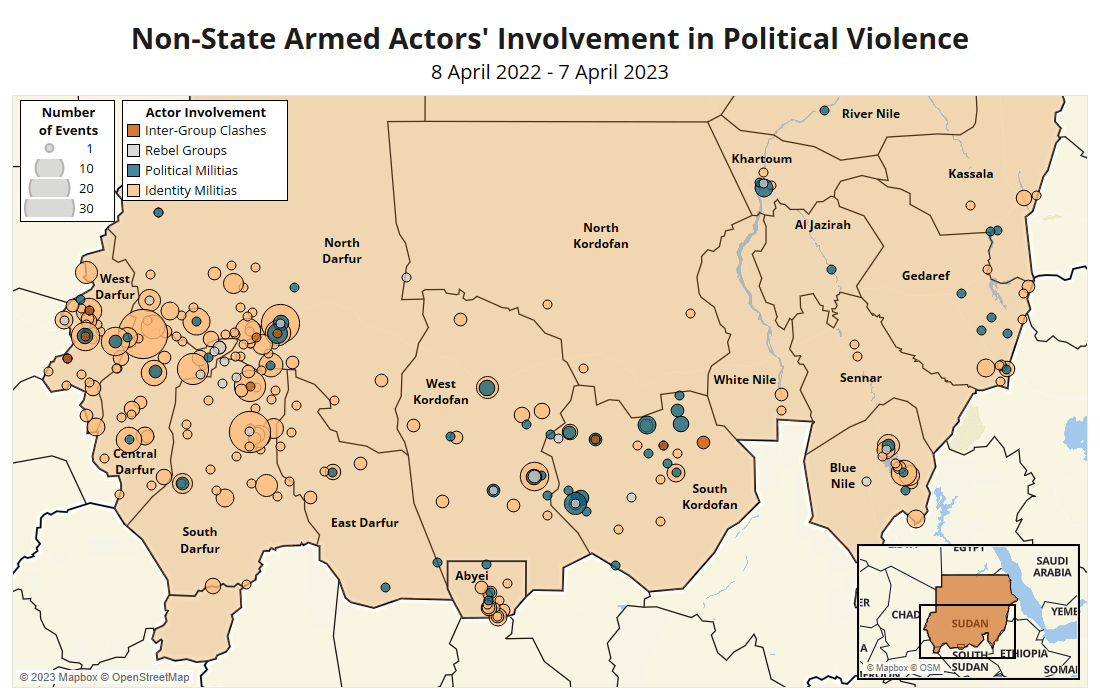

Notably, at least since 2019, rebel groups’ involvement in political violence in the country has decreased, while identity-based armed groups, such as communal, ethnic, and clan militias, have been increasingly involved in violence. In the past year, rebel groups and political militias were involved in only 3% and over 10% of all violent activity in the country, respectively. Meanwhile, identity-based militias were involved in over 60% of all political violence in Sudan, mostly in Darfur (see map below). This demonstrates a continuing shift in the nature of violence and actors involved – from regular, traditional armed groups to irregular identity militias. The shift away from rebel groups has been underway for a long time, and can be attributed to ceasefire arrangements, the decrease in the number of rebel groups and splinter factions, as well as weakened capacity within the rebel groups, among other things. On the other hand, resource and land pressures have undermined cooperation between communal groups, leading to increased violence over access to land and resources. The lack of institutional capacity to manage conflict and the power vacuum resulting from the political upheaval in the country further exacerbated communal violence as security forces had to focus on maintaining security in main cities and confronting demonstrations. The provision of security has been poor, and the widespread availability of weapons has further contributed to the rapid escalation of violence following individual incidents.23Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Populations at Risk: Sudan,’ 28 February 2023; Abdi Latif Dahir, ‘‘They Keep Killing Us’: Violence Rages in Sudan’s Darfur Two Decades On,’ New York Times, 19 March 2022

Given these trends, it is likely that the current political process will not have a significant impact on violence in the peripheries of Sudan, as many of the rebel groups in Darfur, Kordofan, and Blue Nile have had minimal involvement in the violence in the past year. The two rebel groups with substantial territorial control and increasing role in political violence – Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) and Abdul Wahid al-Nur faction of the SLM/A – are not engaged in the political process.24PanaPress, ‘Sudan peace talks kick off with parties showing optimism,’ 26 May 2021 From 8 April 2022 to 7 April 2023, these two groups were the most active rebel groups in Sudan, being involved in over 60% of all political violence involving rebel groups in the country. Furthermore, as the disagreements over the integration of the RSF dominate and threaten the current political process, it has overshadowed the discussion on the drivers of conflict in the peripheries.

Sudan has experienced a tumultuous political transition since the ouster of former President al-Bashir. However, since the signing of the framework agreement, there have been signs of progress toward restoring a democratic and civilian government. While there have been some disagreements during the process and most resistance committees still reject the framework agreement, many of the actors who had rejected the agreement joined in the last phases of the process as the FCC-Democratic Bloc accepted the Trilateral Mechanism’s proposal to share power in the transitional government with FFC-Central Council. It is, however, worrying that the current FFC negotiations focus on maintaining stability through accommodating and reforming existing structures rather than fundamentally changing the profoundly ingrained systems that have caused and facilitated violence in the country. Sudan still faces many challenges in the transition process. The most contentious issue is the integration of the RSF and other rebel groups into the military, in addition to reaching a peace agreement with SLM/A Abdul Wahid and SPLM-N Abdelaziz al-Hilu factions. Lastly, the rise in inter-communal violence and identity militia activity is another issue threatening peace and stability in Sudan that requires immediate attention.

Ali Mahmoud Ali is an Africa Researcher at ACLED and has been with the organization since April 2022. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Mathematics and Computer Sciences from the University of Khartoum Faculty of Mathematical Science and Informatics.

Elham Kazemi is an Analysis Coordinator at ACLED and has been with the organization since November 2018, originally hired as a North Africa Researcher. She currently supervises the Africa conflict observatories. Elham holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of California, Irvine, and an LLM in International Human Rights Law from the University of Notre Dame.

Regions:

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) is a disaggregated data collection, analysis, and crisis mapping project.

ACLED is the highest quality and most widely used real-time data and analysis source on political violence and protest around the world. Practitioners, researchers, journalists, and governments depend on ACLED for the latest reliable information on current conflict and disorder patterns.

ACLED is a registered non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status in the United States.

Please contact [email protected] with comments or queries regarding the ACLED dataset.