artran

artran

The past few weeks have provided a shock for market participants who are, let’s say, green behind the ears, and evoked painful memories for those who lived through the market turmoil of the Great Financial Crisis (henceforth the GFC). Crises are most often understood in the rearview mirror, and few market participants are generally able to comprehend what’s happening at the time the events unfold. The savings and loan crisis of the 1980s provides perhaps the most accurate parallel to today’s banking crisis, however, and while it’s difficult to fault today’s investors for seeing the next GFC around every corner, we believe that it is not the case that the current problems in the banking sector will prove existential to the largest players in the space.

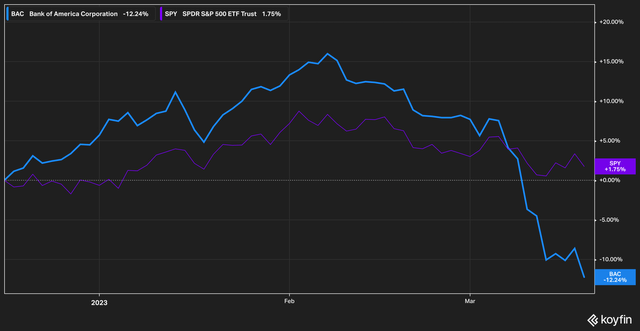

In this article we’ll outline why we think the selloff in Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) stock is overdone.

Koyfin

Koyfin

With a drop in the last few weeks nearing 20%, we think the stock currently presents a strong buying opportunity.

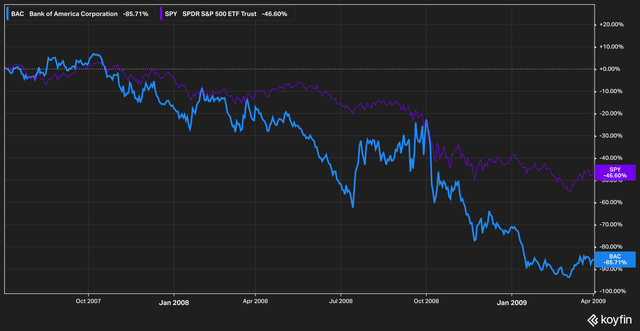

A quick reminder of where Bank of America once found itself is in order. In 2008, the banking sector as a whole found itself on the hook for many billions of poor mortgage loans that had been packaged into instruments called Collateralized Debt Obligations [CDOs], which was supposed to reduce the overall risk of owning mortgages as a creditor. We won’t go into more detail than that, go watch (or better yet, read) The Big Short for more detail.

Bank of America’s stock was, deservedly, punished:

Koyfin

Koyfin

From July 2007 to April 2009, Bank of America’s stock fell by more than 80%, and traded hands for roughly $6.

The bank, for what it’s worth, was in good enough health to survive and to indeed purchase struggling institutions (Merrill Lynch) at the behest of the federal government.

Since April 2009, Bank of America has generated price returns roughly in line with the broader market, reaching a high of over 500% before the broad market re-valuation of 2022 brought the price low again.

Unlike the GFC, however, today’s crisis doesn’t revolve around reckless risks being taken by Wall Street salesman and likely won’t result in a movie where Margot Robbie explains the situation to viewers while in a bathtub drinking champagne.

The crisis today is much more boring, and much more akin to (as mentioned previously) the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s–it involves banks poorly managing run-of-the-mill interest rate and duration risk against deposits.

The basic business of a bank is to take deposits and lend against them for a higher interest rate than it pays those depositors, thus earning a profit on the spread. This core function is underpinned by the trust of the depositors. If depositors as a whole do not feel confident in the bank’s ability to give them back their money, then mass hysteria sets in and bank runs (a la ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ and Silicon Valley Bank (SIVB)) take place.

This is why banks aren’t allowed to lend out the full amount of their deposits–they are required to hold reserves and hold a portion of their loans against equity. This creates a buffer that allows banks to survive even if a larger-than-expected amount of depositors suddenly demand their money back (but only a bit larger than expected).

This, then, is the source of capital ratios and stress tests, which the largest, most systematically important banks were routinely subjected to post-GFC.

Banks–with the exception of Credit Suisse (CS), which had many, many problems prior to the current crisis–that are in the spotlight today are, for the most part, facing potential liquidity problems as their long-duration holdings (I.e. those interest bearing liabilities that were purchased with customer deposits) are suddenly paying out a pittance compared to what can be purchased even on the front end of the yield curve.

(For a more in-depth example of this, please check out our recent piece outlining these difficulties at Charles Schwab (SCHW)).

The basic premise is this. Prior to 2022, interest rates were quite low, and it was difficult to find yield on invested dollars without looking way down the yield curve, which essentially means buying long-dated bonds (more than 10 years in most cases) rather than bonds with maturity of, say, 2 years, or just something less than 10 generally.

As the federal reserve raised rates in 2022 at a rather rapid clip from zero up to near 5%, this created problems for banks that had purchased the long-dated bonds described above. They now held investments on their books that were worth significantly less on paper than when they were purchased due to higher prevailing interest rates, and depositors (rightfully so) were demanding higher yields on their deposits which these regional banks would be hard-pressed to provide, especially when their own investments were purchased pre-2022 and were generally yielding very little. (Schwab Bank’s investments, for example, yield roughly 1.5% on a 10-year basis.)

While this sort of pinch has affected regional banks, the big, systemically important players (again, extracting Credit Suisse from the equation), have largely been able to keep their noses clean, much as they did during the savings and loan crisis of the ’80s.

This is due to a number of factors. First, deposits are generally sticky, meaning that bank customers don’t change banks frequently or without great cause, generally. This is largely why the biggest banks can get away with paying out the lowest interest rates on deposits, and why smaller players generally feel more pressure to pay a competitive rate.

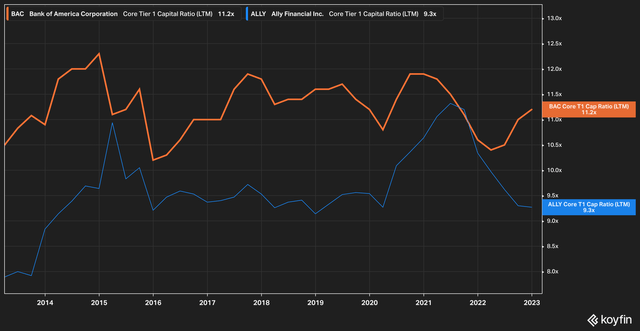

Koyfin

Koyfin

This is why, when we examine capital ratios over a long period, we see that entities like Bank of America are able to successfully maintain higher (read: more secure) capital ratios compared to even low-cost, digital competitors like Ally Financial (ALLY).

In referencing the above chart, we point out that Bank of America was able to do something in 2022 that very few regional banks were able (or had the foresight) to do–raise their Tier 1 capital ratio after a dip in 2022 when interest rates were rising.

In fact, for 2022, Bank of America noted in page 31 of its 10K that assets (including held-for-sale assets) had decreased by $12.5 billion. For comparison, this is far less than the losses posted by Schwab, which has a market cap of about half of Bank of America’s, and less than a third of its amount of bank deposits.

Overall, we see very little reason for investors to be concerned that the current problems regional banks are experiencing are likely to extend to major, systemically important banks like Bank of America. With expanding capital ratios and a steady deposit base of $1.9 trillion (with a ‘t’), we believe that the recent selloff in Bank of America is overdone and presents a buying opportunity.

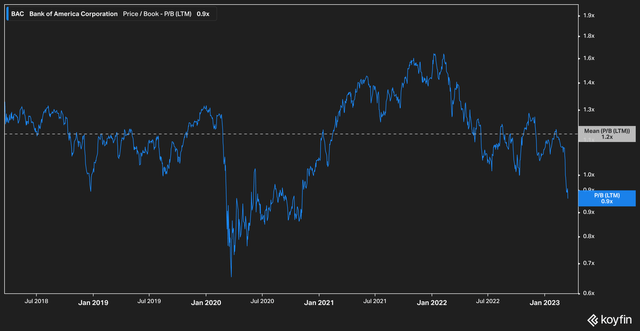

Koyfin

Koyfin

To support this, we reference the fact that the recent selloff has brought Bank of America to less than parity with its book value. Reflecting its gargantuan nature, over the past five years the stock has traded at an average of 1.2x book value per share. Much like the panic-induced ‘flash recession’ of early 2020, we believe that buyers here are likely to be rewarded in the long run.

This article was written by

Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: Disclaimer: The information contained herein is for informational purposes only. Nothing in this article should be taken as a solicitation to purchase or sell securities. Factual errors may exist and will be corrected if identified. Before buying or selling any stock, you should do your own research and reach your own conclusion or consult a financial advisor. Investing includes risks, including loss of principal.